A GUEST CONTRACT FOR TODAY SHOW. SIGNED BY JAZZ LEGEND. ON 8.5X11 INCH PAPER. Wynton Learson Marsalis is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. Successful jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis (born 1961) is America’s top modern purist of the genre. Influenced by the jazz artists from the early 1900s through the 1960s and annoyed with the music labeled “jazz” in the 1970s, Marsalis took on the mission of not only creating “true” jazz, but teaching its definition as well. Asuccessful jazz and classical musician and composer, Marsalis had won more than eight Grammy awards and released over 30 albums in both genres by the late 1990s. In 1997, he received the first Pulitzer Prize ever awarded for nonclassical music. He also co-founded and directed the ground-breaking jazz program at New York’s Lincoln Center, and became an influential jazz educator for America’s youth. Marsalis was born into a family of musicians on October 18, 1961, in New Orleans. His father, Ellis Marsalis, played piano and worked as a jazz improvisation instructor at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts. Before dedicating her life to raising her six sons, Dolores Marsalis sang in jazz bands. The second eldest child, Wynton’s older brother Branford set the stage as the family’s first musical prodigy. Branford Marsalis played both clarinet and piano by the time he entered the second grade, and eventually became a professional saxophonist. Wynton Marsalis didn’t follow his brother’s lead quite as diligently, however. When he was six years old, his father played with Al Hirt, who gave the young Marsalis one of his old trumpets. Wynton Marsalis made his performing debut at the tender age of seven when he played “The Marine Hymn” at the Xavier Junior School of Music. As a child, Marsalis didn’t take practicing the trumpet very seriously. He spent more time with his school work, playing basketball, and participating in Boy Scout activities. Discovered Influences in Two Genres. When Marsalis was 12, his family moved from Kenner, Louisiana, to New Orleans. When he listened to a recording by jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown, he was moved to take his trumpet seriously. “I didn’t know someone could play a trumpet like that, ” Marsalis later told Mitchell Seidel in Down Beat. Soon after, a college student gave Marsalis an album by classical trumpet player Maurice Andre, which also sparked his interest in classical music. Marsalis began taking lessons from John Longo in New Orleans, who had an interest in both genres, as well. “I hardly ever even paid him, ” Marsalis recalled to Howard Mandell in Down Beat, and he used to give me two-and three-hour lessons, never looking at the clock. Marsalis attended Benjamin Franklin High School in New Orleans, where he graduated with a 3.98 grade point average on a 4.0 scale. He became a National Merit Scholarship finalist and received scholarship offers from Yale University, among other prestigious schools. He also attended the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts. At the age of 14, he won a Louisiana youth competition. This award granted him the opportunity to perform with the New Orleans Philharmonic Orchestra as a featured soloist. During his high school years, he played a variety of music with a number of groups, including first trumpet with the New Orleans Civic Orchestra, the New Orleans Brass Quintet, an a teenage funk group called the Creators, along with his brother Branford. In 1977, Marsalis won the “Most Outstanding Musician Award” at the Eastern Music Festival in North Carolina. Started Spreading the News. He went on to study music at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood in Massachusetts, where he received their Harvey Shapiro Award for the outstanding brass player. He turned down the scholarship offers from Ivy League schools to attend New York’s Juilliard School of Music on full scholarship. While in school, he played with the Brooklyn Philharmonia and the Mexico City Symphony. He supported himself with a position in the pit band for Sweeney Todd on Broadway. In 1980, Art Blakey asked Marsalis to spend the summer touring with his Jazz Messengers. His performances began to attract national attention, and he eventually became the band’s musical director. While on the road with Blakey, Marsalis decided to change his image and began wearing suits to his performances. “For us, it was a statement of seriousness, ” Marsalis told Howard Reich in Down Beat. We come out here, we try to entertain our audience and play, and we want to look good so they can feel good. The following year, Marsalis decided to leave Juilliard to continue his education on the road. He played with Blakey and received an offer to tour with Herbie Hancock’s V. Marsalis jumped at the chance, as the V. Included bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams, who had both played with Miles Davis. “I knew he was only 19, just on the scene-it’s a lot to put on somebody, ” Hancock told Steve Bloom in Rolling Stone. But then I realized if we don’t hand down some of this stuff that happened with Miles, it’ll just die when we die. Marsalis performed throughout the United States and Japan with the V. And played on the double album Quartet. The increased attention led to an unprecedented recording contract with Columbia Records for both jazz and classical music. He released his self-titled debut album as a leader in 1981. Later that year, he formed his own jazz band with his brother Branford, Kenny Kirkland, Jeff Watts, and bassists Phil Bowler and Ray Drummond. His success didn’t go unnoticed in his hometown, either. New Orleans Mayor Ernest Morial proclaimed a Wynton Marsalis Day in February of 1982. Wynton Marsalis recorded one side of an album with his father Ellis and Branford Marsalis, called For Fathers and Sons. The other side was recorded by saxophonist Chico Freeman and his father Von Freeman. In 1983, Marsalis released jazz and classical LPS simultaneously. The recording and Marsalis received many comparisons to Miles Davis and other musicians of the 1960s. “We don’t reclaim music from the 1960s; music is a continuous thing, ” Marsalis explained to Mandell in Down Beat. We’re just trying to play what we hear as the logical extension. A tree’s got to have roots. He recorded his classical debut, Trumpet Concertos, in London with Raymond Leppard and the National Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1984, Marsalis set another precedent by becoming the first artist to be nominated or win two Grammy awards in two categories during the same year. Big Sounds in the Big Apple. He won another Grammy award in 1987 for his album Marsalis Standard Time Vol. During the same year, he co-founded the Jazz at Lincoln Center program in New York City. When the program began, Marsalis became the artistic director for the eleven-month season. As part of his contract, he had to compose one piece of music for each year. Despite his new position, he continued to record and tour in both jazz and classical music. He released Majesty of the Blues in 1989 and The Resolution of Romance in 1990. He dedicated the latter to his mother, and it included contributions from his father Ellis and his brother Delfeayo. “If you are really dealing with music, you are trying to elevate consciousness about romance, ” Marsalis explained to Dave Helland in Down Beat. Music is so closely tied up with sex and sensuality that when you are dealing with music, you are trying to enter the world of that experience, trying to address the richness of the interaction between a man and a woman, not its lowest reduction. Marsalis’ study of New Orleans styles resulted in a trilogy called Soul Gestures in Southern Blue in 1990. Describing the set, Howard Reich wrote in Down Beat, the crying blue notes of’Levee Low Moan,’ the church harmonies of’Psalm 26,’ the sultry ambiance of’Thick in the South’ all recalled different settings and epochs in New Orleans music. And yet the tautness of Marsalis’ septet, the economy of the motifs, and the adventurousness of the harmonies proclaimed this as new music, as well. Using history to create his present sound became Marsalis’ goal, along with exploring the rich tapestry of the different eras and styles of jazz. His first commission for the jazz program at Lincoln Center, In This House, On This Morning was performed in 1993. In it, he used the music of the African-American church as his primary inspiration. Evolved into Jazz Spokesman. In the fall of 1994, Marsalis announced that his septet had disbanded. However, he continued composing, recording, and performing. The following year, he produced a four-part video series called Marsalis on Music, which aired on PBS. In May of 1995, his first string quartet, (At the) Octoroon Balls debuted at the Lincoln Center. He continued to release classical works as well. He re-recorded the Haydn, Hummel, and Leopold Mozart concertos from Trumpet Concertos in 1994. Two years later, he released In Gabriel’s Garden, which he recorded with the English Chamber Orchestra and Anthony Newman on harp-sichord and organ. “I want to keep developing myself as a complete musician, ” Marsalis told Ken Smith in Stereo Review, so I take on projects either to teach me something new or else to document some development. With this new Baroque album, I felt that I’d never really played that music before with the right authority or rhythmic fire. ” Marsalis produced the Olympic Jazz Summit at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, and won 1996 Peabody Awards for both Marsalis on Music and for his National Public Radio Show “Wynton Marsalis: Making the Music. At the end of 1996, Time magazine named him one of America’s 25 Most Influential People. A major part of his influence went out to the country’s youth. When he’s not working on his own music, he traveled to schools across the country to talk about music in an effort to continue the tradition of jazz. “I’m always ready to put my own neck on the line for change, ” Marsalis told Lynn Norment in Ebony. No school is too bad for me to go to. I’ll try to teach anybody. We are all striving for the same thing, to make our community stronger and richer. That’s what the jazz musician has always been about. In April of 1994, his biggest piece, Blood on the Fields, had its debut performance at the Lincoln Center. Marsalis composed the oratorio for three singers and a 14-piece orchestra, and it described the story of two Africans, Leona and Jesse, who found love despite the difficulties of American slavery. “I wanted to orchestrate for the larger ensemble and write for voices-something I’d never done, ” Marsalis said to V. Peterson in a People magazine interview. I wanted to make the music combine with the words, yet make the characters seem real. With Blood on the Fields, Marsalis won the first non-classical Pulitzer Prize award in history. Because of his piece, the selection board changed the criteria from “for larger forms including chamber, orchestra, song, dance, or other forms of musical theater” to for distinguished musical composition of significant dimension. Columbia Records released the oratorio on a three-CD set in June of 1997. He followed the release with recordings of two other previously performed works on one album. His collaboration with New York City Ballet director, Peter Martins’ Jazz/ Six Syncopated Movements and Jump Start written for ballet director, Twyla Tharp, were both included on the record. Marsalis’ work in jazz and classical music combined with his often outspoken attitude toward musical integrity surrounded him with controversy throughout his career. Despite the criticism, his talent was never questioned. As Eric Alterman described in The Nation, he’s a man universally acknowledged to be a master musician and perhaps the most ambitious composer alive. Who gave you your first trumpet? I got my first trumpet when I was six from Al Hirt. My father was playing piano in his band, and as a Christmas present I received a trumpet – a LeBlanc. What influence did your father/mother have on your desire to become a musician? My father was an example to me, because of the type of integrity he had when he would play. I also liked the musicians that my father played with. They were always around: James Black the drummer, Nat Perlatt on saxophone. I liked Richard Payne the bass player, the great clarinetist Alvin Batiste. John Fernandez was a great trumpet player and a teacher. I didn’t like the music they played so much but I liked them. And I always liked to hang at the gigs and listen to them play and see what was going on. Also, for that whole generation of Southern musicians – like my father, like Alvin Batiste – playing the music was a stab against segregation. It was a matter of their identity, of their high-minded nature and of them as men. In their own way, it was a sign of protest against the environment they grew up in. Not just in terms of segregation of whites, because black people were also apathetic toward what they were playing. Some people considered it to be devil’s music, and others just considered it to be a waste of time. So they had certain defiance in their personality that I always could gravitate toward in life. My mama stayed on us about practicing. She took her time to take us to music classes and see that we received an education. So, in terms of discipline and investing her time and love and energy in us – she was always doing that for me and all my brothers. Did you always want to be a jazz musician or did you try other genres first? I always wanted to be a jazz musician because I liked the way that they played, but you couldn’t get a gig playing jazz. So I played funk gigs all the time with a band called Funky Creative. We used to play clubs, dances, proms. I joined the band when I was 12, and I played until I was 16. We’d work every weekend, and sometimes on the weekdays. We had one of the most popular bands in New Orleans, playing Top 40 cover songs. This was the 70’s, so everybody had their afro, bellbottom jeans, platform heeled shoes. We had the whole uniform – we had these jumpsuits and this all this crazy looking stuff. It took us an hour just to put our equipment up. Which artists have influenced you the most? A lot of jazz musicians like Monk, Duke, Miles, Charlie Parker, Dizzy, Jelly Roll Morton, Wayne Shorter. I listen to a lot of them and try to incorporate things that I like into my own style. Trumpet players such as Maurice Andre, Adolph Hofner, Cootie Williams, Ray Nance and Sweets Edison have all had an influence on my style. When I was in high school, Clark Terry influenced me a lot. I can’t forget him. In terms of classical music, I like Stravinsky and Beethoven a lot. What is the best advice another musician has ever given you? One time Sweets Edison told me, Don’t play like you’re trying to prove that you can play. Are different skills required to perform classical vs. In jazz, you have a heavier sound, a heavier attack than in classical. Also, classical music is all written down, so you have to concentrate on executing it. In jazz, you’re making the music up, so you have to know the harmony of the songs, and how to interact with the different musicians. It’s a matter of reflexes. Who are the greatest trumpeters (or musicians of) of all time? The first one is Gottfried Reich. Bach wrote the Brandenberg Concerto for him. In mythology, it really starts with Gabriel. Gabriel actually was a woman. They were cheating women even back then. Her name was actually Gabrielle. She was the first great trumpet player. Then you have the German trumpet player, Gottfried Reich. Then there’s Anton Veidenger. He’s the guy who the Haydn trumpet concerto and the Hummel trumpet concerto were written for. Then you have all the great cornet soloists. There are so many of them. A lot of Americans. Patrick Gilmore had a great band after the Civil War. Then there were all the great soloists with John Philip Sousa. You have Herbert L. Clarke, Krill, George Swift, Jules Levy, Del Stagers. Each one had a different specialty. Some could play double tongue real fast, some slur, some do triple tongue, some trick fingers. Everybody had a different thing. Some played real sweet. Matthew Arbuckle used to have a battle of cornets. You’d see them go in. It would be who could play the most. Then you got the jazz musicians: Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Freddy Keppard, Buddy Petit. Then you get to Red Allen, and then you’ve got Louis Armstrong. From there, you get all the trumpet players influenced by him. Various trumpet players like Buddy Barry, Cootie Williams, Rex Stewart, Ray Nance, Sweets Edison, Buck Clayton, Roy Eldrige, Doug Mascoll. There are a lot of people. At the same time, there are the great classical trumpet players, William Vacchiano and Max Schlossberg. Then you come up in the more modern era with Dizzy and Miles, Freddy Hubbard, Don Ellis, Don Cherry, Booker Little, Lee Morgan. In classical music, there’s Aldoph Herseth, a great trumpet player. There’s Maurice Andre, a classical trumpet player, Rafael Mendez, an all around unbelievable trumpeter, Doc Sevrenson, Al Hirt. You start to get a lot of great trumpet players of different types. Do you know everything there is to know about trumpet playing? There’s so much to know, it’s hard to know everything about anything. There’s so much to know, period. What performers today do you find to be the most interesting or promising? I like Nicholas Payton, I like Roy Hargrove, Terence Blanchard. Dave Douglas is interesting. You’ve got a lot of young trumpet players. Omar Butler, a young student at Juilliard. Keyon Harold is an interesting trumpet player who plays with a lot of feeling. Jermanie Smith, Mike Rodriguez, Trombone Shorty on the trumpet from New Orleans can play. Dominic Faranacci, Brandon Lee and Tatum Greenblatt are a few of the great young kids coming out of high school. What advice would you give a youngster who is interested in playing the trumpet? You don’t have to practice for hours. Just get on your horn every day and listen to the people who really can play. Just try to keep going and develop. Why are you so involved in education, master classes, etc. My father was always teaching, and the musicians he played with were all teachers. I was always taking classes. I just grew up around it. What qualities do you look for in a band member? Individuality, deep sound and a willingness to do work. Is your new trumpet one of a kind? Tell us about it. It’s made by Dave Monette and it’s one of a kind-he made it for me. It has personalized engravings from all aspects of my life. Symbols of playing, the great “j master” Marcus Roberts is on there, things about my kids. This is the first trumpet Monette ever made in this way. He has subsequently made other trumpets like that. Not with the same designs on it, of course. You’ve described jazz as America’s music. Well not to be a sloganist, but it’s part of the fabric of our country-the way we speak our language, the way we interact with each other, the tensions and dynamics that make our country what it is, the basic forms and things that we use to comport ourselves-all of that is in jazz. You can see it in songs like “Birmingham Breakdown, ” Duke Ellington’s East St. Louis Toodle-oo, ” and “Sidewalks of New York. Jazz also shows the influence of the Broadway show tune, which is an American tradition. There’s also the idea of improvisation, which was developed in America. There’s a whole relationship between the history of the music and race relations in our country. Jazz just deals with a lot of different aspects of our way of life. When you became the first jazz artist to win a Pulitzer Prize (for “Blood On The Fields”) you spoke often of Duke Ellington. I feel it’s always important to stress the fact that I’m a part of a continuum, and that our music continues. It’s not a fad, it continues on. And Duke laid the ground work for us to understand how to compose with the blues harmonies and what the American orchestra was. He laid out the framework for it. And it’s important for all the musicians that come after to realize it’s a continuum. It doesn’t live and die with anyone personally. Is it true that you often have several different projects underway at once? Why do you work so hard? I like to do a lot of different things. I like to stay busy. I grew up working all the time, and that’s just what I like to do. It doesn’t bother me really. I’m used to it. Your historic “Swinging Into the 21st” series ushered in the new millennium. What are you striving to achieve in these years ahead? We’ve laid out a good framework with Jazz at Lincoln Center. In the coming years, we want to continue to play the great music of our tradition, and continue to write new music that addresses the fundamentals while introducing new things. We want to collaborate with more musicians around the world-New Zealand musicians, Argentinean musicians-in order to deal with the ongoing relationship of jazz music to other forms of music. This is something that was well established by Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington and Miles Davis with records like Sketches of Spain. Dizzy Gillespie did many works with Afro-Cuban music and later with the United Nations orchestra. I want to continue to go in that direction-continue to collaborate with different arts and arts organizations, like the New York Philharmonic, the New York City Ballet, The Chamber Music Society, The Film Society and Lincoln Center Institute. We want to do a lot of different things, get involved in some theater projects, try and write an opera, try to write a mass. I just want to expand and write more sophisticated music. In what way do you think the Internet will impact the arts? The Internet is just transference of information, and music is about information- passing information on with you. What you think, what you feel, what is revealed to you to anybody who’s interested in it. It’s just another tool of communication. What accomplishment are you most pleased with as Artistic Director of JALC? That we’ve successfully challenged the status quo of our music. When we started, nobody was thinking about Duke Ellington’s music and the seriousness of jazz as an art form. We’ve been able to challenge a lot of what was held to be true because of the presence of Jazz at Lincoln Center. We’ve done dances, we’ve brought musicians in from all over the world, we’ve played concerts. We’ve commissioned pieces and done first-ever concerts. Gerry Mulligan requested that, when he died, we do his posthumous concert and play his music. He told me to make sure that I do it. Just the fact that a musician of that magnitude and stature would make that request is a serious thing. He wanted us to play the New Orleans March, and we did. That was one of the greatest tributes we could have. Wynton Marsalis is an internationally acclaimed musician, composer and bandleader, an educator and a leading advocate of American culture. He has created and performed an expansive range of music from quartets to big bands, chamber music ensembles to symphony orchestras and tap dance to ballet, expanding the vocabulary for jazz and classical music with a vital body of work that places him among the world’s finest musicians and composers. Always swinging, Marsalis blows his trumpet with a clear tone, a depth of emotion and a unique, virtuosic style derived from an encyclopedic range of trumpet techniques. When you hear Marsalis play, you’re hearing life being played out through music. Marsalis’ core beliefs and foundation for living are based on the principals of jazz. He promotes individual creativity (improvisation), collective cooperation (swing), gratitude and good manners (sophistication), and faces adversity with persistent optimism (the blues). With his evolved humanity and through his selfless work, Marsalis has elevated the quality of human engagement for individuals, social networks and cultural institutions throughout the world. Wynton was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, on October 18, 1961, to Ellis and Dolores Marsalis, the second of six sons. At an early age, he exhibited a superior aptitude for music and a desire to participate in American culture. At age eight Wynton performed traditional New Orleans music in the Fairview Baptist Church band led by legendary banjoist Danny Barker, and at 14 he performed with the New Orleans Philharmonic. During high school Wynton performed with the New Orleans Symphony Brass Quintet, New Orleans Community Concert Band, New Orleans Youth Orchestra, New Orleans Symphony, various jazz bands and with the popular local funk band, the Creators. At age 17 Wynton became the youngest musician ever to be admitted to Tanglewood’s Berkshire Music Center. Despite his youth, he was awarded the school’s prestigious Harry Shapiro Award for outstanding brass student. Wynton moved to New York City to attend Juilliard in 1979. When he started gigging around the City, the grapevine began to buzz. The excitement around Wynton attracted the attention of Columbia Records executives who signed him to his first recording contract. In 1980 Wynton seized the opportunity to join the Jazz Messengers to study under master drummer and bandleader Art Blakey. It was from Blakey that Wynton acquired his concept for bandleading and for bringing intensity to each and every performance. In the years to follow Wynton performed with Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie, Sweets Edison, Clark Terry, John Lewis, Sonny Rollins, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams and countless other jazz legends. Wynton assembled his own band in 1981 and hit the road, performing over 120 concerts every year for 15 consecutive years. With the power of his superior musicianship, the infectious sound of his swinging bands and a far-reaching series of performances and music workshops, Marsalis rekindled widespread interest in jazz throughout the world and inspired a renaissance that attracted a new generation of fine young talent to jazz. A look at the more distinguished jazz musicians to emerge for the decades to follow reveals the efficacy of Marsalis’ workshops and includes: James Carter, Christian McBride, Roy Hargrove, Marcus Roberts, Wycliffe Gordon, Harry Connick Jr. Nicholas Payton, Eric Reed and Eric Lewis, to name a few. Wynton also embraced the jazz lineage to bring recognition to the older generation of overlooked jazz musicians and prompted the re-issue of jazz catalogs by record companies worldwide. Wynton’s love of the music of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and others drove him to pursue a career in classical music as well. He recorded the Haydn, Hummel and Leopold Mozart trumpet concertos at age 20. His debut recording received glorious reviews and won the Grammy Award® for Best Classical Soloist with an Orchestra. Marsalis went on to record 10 additional classical records, all to critical acclaim. Wynton performed with leading orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Boston Pops, The Cleveland Orchestra, Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, English Chamber Orchestra, Toronto Symphony Orchestra and London’s Royal Philharmonic, working with an eminent group of conductors including: Leppard, Dutoit, Maazel, Slatkin, Salonen and Tilson-Thomas. A timeless highlight of Wynton’s classical career is his collaboration with soprano Kathleen Battle on their recording Baroque Duet. Famed classical trumpeter Maurice André praised Wynton as potentially the greatest trumpeter of all time. His recordings consistently incorporate a heavy emphasis on the blues, an inclusive approach to all forms of jazz from New Orleans to modern jazz, persistent use of swing as the primary rhythm, an embrace of the American popular song, individual and collective improvisation, and a panoramic vision of compositional styles from dittys to dynamic call and response patterns (both within the rhythm section and between the rhythm section and horn players). Wynton Marsalis is a prolific and inventive composer. He is the world’s first jazz artist to perform and compose across the full jazz spectrum from its New Orleans roots to bebop to modern jazz. He has also composed a violin concerto and four symphonies to introduce new rhythms to the classical music canon. Marsalis collaborated with the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society in 1995 to compose the string quartet At The Octoroon Balls, and again in 1998 to create a response to Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale with his composition A Fiddler’s Tale. Several prominent choreographers embraced Wynton’s inventiveness with commissions to compose suites to fuel their imagination for movement. This impressive list includes Garth Fagan (Citi Movement-Griot New York & Lighthouse/Lightening Rod), Peter Martins at the New York City Ballet (Jazz: Six Syncopated Movements and Them Twos), Twyla Tharp with the American Ballet Theatre (Jump Start), Judith Jamison at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre (Sweet Release and Here. Now), and Savion Glover (Petite Suite and Spaces). Wynton reconnected audiences with the beauty of the American popular song with his collection of standards recordings (Standard Time Volumes I-VI). He re-introduced the joy in New Orleans jazz with his recording The Majesty Of The Blues. And he extended the jazz musician’s interplay with the blues in Uptown Ruler, Levee Low Moan, Thick In The South and other blues recordings. Marsalis introduced a fresh conception for extended form compositions with Citi Movement, his sanctified In This House, On This Morning and Blood On The Fields. His inventive interplay with melody, harmony and rhythm, along with his lyrical voicing and tonal coloring assert new possibilities for the jazz ensemble. In his dramatic oratorio Blood On The Fields, Wynton draws upon the blues, work songs, chants, spirituals, New Orleans jazz, Ellingtonesque orchestral arrangements and Afro-Caribbean rhythms — using Greek chorus-style recitations with great affect to move the work along. The New York Times Magazine said Blood On The Fields marked a symbolic moment when the full heritage of the line, Ellington through Mingus, was extended into the present. ” The San Francisco Examiner stated, “Marsalis’ orchestral arrangements are magnificent. Duke Ellington’s shadings and themes come and go but Marsalis’ free use of dissonance, counter rhythms and polyphonics is way ahead of Ellington’s mid-century era. Blood on the Fields became the first jazz composition ever to be awarded the coveted Pulitzer Prize in Music in 1997. Wynton extended his achievements in Blood On The Fields with All Rise, an epic composition for big band, gospel choir, and symphony orchestra – a classic work of high art – which was performed by the New York Philharmonic under the baton of Kurt Masur along with the Morgan State University Choir and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra (December 1999). Marsalis collaborated with Ghanaian master drummer Yacub Addy to create Congo Square, a groundbreaking composition combining harmonies from America’s jazz tradition with fundamental rituals in African percussion and vocals (2006). For the anniversary of the Abyssinian Baptist Church’s 200th year of service, Marsalis blended Baptist church choir cadences with blues accents and big band swing rhythms to compose Abyssinian 200: A Celebration, which was performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and Abyssinian’s 100 voice choir before packed houses in New York City (May 2008). In the fall of 2009 the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra premiered Marsalis’ composition Blues Symphony. Marsalis infused blues and ragtime rhythms with symphonic orchestrations to create a fresh type of enjoyment of classical repertoire. Marsalis further expanded his repertoire for symphony orchestra with Swing Symphony, employing complex layers of collective improvisation. The work was premiered by the renowned Berlin Philharmonic and performed with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra in June 2010, creating new possibilities for audiences to experience a symphony orchestra swing. Wynton made a significant addition to his oeuvre with Concerto in D, a violin concerto composed for virtuoso Nicola Benedetti. The concerto is in four movements, “Rhapsody, ” “Rhondo, ” “Blues, ” and Hootenanny. With this masterful composition Marsalis celebrates the American vernacular in ultra-sophisticated ways. Its fundamental character is Americana with sweeping melodies, jazzy orchestral dissonances, blues-tinged themes, fancy fiddling and a rhythmic swagger. Concerto in D received its world premiere by the London Symphony Orchestra in November 2015 and its American premiere by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Ravinia in July 2016. In December 2016 Marsalis again demonstrated his expansive musical imagination and dexterity for seasoning the classical music realm with jazz and blues influences with The Jungle, performed by the New York Philharmonic along with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. “The Jungle, ” according to Marsalis, is a musical portrait of New York City, the most fluid, pressure-packed, and cosmopolitan metropolis the modern world has ever seen. The New York Philharmonic and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra re-united to present The Jungle in Shanghai in July 2017. Marsalis’ rich and expansive body of music for the ages places him among the world’s most significant composers. Television, Radio & Literary. In the fall of 1995 Wynton launched two major broadcast events. In October on PBS he premiered Marsalis On Music, an educational television series on jazz and classical music. Written and hosted by Marsalis, the series and was enjoyed by millions of parents and children. Writers distinguished Marsalis On Music with comparisons to Leonard Bernstein’s celebrated Young People’s Concerts of the 50s and 60s. That same month National Public Radio aired the first of Marsalis’ 26-week series entitled Making the Music. These entertaining and insightful radio shows were the first full exposition of jazz music in American broadcast history. Wynton’s radio and television series were awarded the most prestigious distinction in broadcast journalism, the George Foster Peabody Award. The Spirit of New Orleans, Wynton’s poetic tribute to the New Orleans Saints’ first Super Bowl victory (Super Bowl XLIV) also received an Emmy Award for Outstanding Short Feature (2011). From 2012 to 2014 Wynton served as cultural correspondent for CBS News, writing and presenting features for CBS This Morning on an array topics from Martin Luther King, Jr. Nelson Mandela and Louis Armstrong to Juke Joints, BBQ, the Quarterback & Conducting and Thankfulness. Marsalis has written six books: Sweet Swing Blues on the Road, Jazz in the Bittersweet Blues of Life, To a Young Musician: Letters from the Road, Jazz ABZ (an A to Z collection of poems celebrating jazz greats), Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life and Squeak, Rumble, Whomp! A sonic adventure for kids. Wynton Marsalis has won nine Grammy Awards® in grand style. In 1983 he became the only artist ever to win Grammy Awards® for both jazz and classical records; and he repeated the distinction by winning jazz and classical Grammys® again in 1984. Honorary degrees have been conferred upon Wynton by over 30 of America’s leading academic institutions including Columbia, Harvard, Howard, Princeton and Yale (see Exhibit A). Elsewhere Wynton was honored with the Louis Armstrong Memorial Medal and the Algur H. Meadows Award for Excellence in the Arts. He was inducted into the American Academy of Achievement and was dubbed an Honorary Dreamer by the I Have a Dream Foundation. The New York Urban League awarded Wynton with the Frederick Douglass Medallion for distinguished leadership and the American Arts Council presented him with the Arts Education Award. Time magazine selected Wynton as one of America’s most promising leaders under age 40 in 1995, and in 1996 Time celebrated Marsalis again as one of America’s 25 most influential people. In November 2005 Wynton Marsalis received The National Medal of Arts, the highest award given to artists by the United States Government. United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan proclaimed Wynton Marsalis an international ambassador of goodwill for the Unites States by appointing him a UN Messenger of Peace (2001). Marsalis was honored with The National Humanities Medal by President Barak Obama in 2015, in recognition of his work in deepened the nation’s understanding of the humanities and broadened American citizens’ engagement with history, literature, languages and philosophy. In 1997 Wynton Marsalis became the first jazz musician ever to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his epic oratorio Blood On The Fields. During the five preceding decades the Pulitzer Prize jury refused to recognize jazz musicians and their improvisational music, reserving this distinction for classical composers. In the years following Marsalis’ award, the Pulitzer Prize for Music has been awarded posthumously to Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane. In a personal note to Wynton, Zarin Mehta wrote. I was not surprised at your winning the Pulitzer Prize for Blood On The Fields. It is a broad, beautifully painted canvas that impresses and inspires. It speaks to us all. I’m sure that, somewhere in the firmament, Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong and legions of others are smiling down on you. Wynton’s creativity has been celebrated throughout the world. He won the Netherlands’ Edison Award and the Grand Prix Du Disque of France. The Mayor of Vitoria, Spain, awarded Wynton with the city’s Gold Medal – its most coveted distinction. Britain’s senior conservatoire, the Royal Academy of Music, granted Mr. Marsalis Honorary Membership, the Academy’s highest decoration for a non-British citizen (1996). The city of Marciac, France, erected a bronze statue in his honor. The French Ministry of Culture appointed Wynton the rank of Knight in the Order of Arts and Literature and in the fall of 2009 Wynton received France’s highest distinction, the insignia Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, an honor that was first awarded by Napoleon Bonaparte. French Ambassador, His Excellency Pierre Vimont, captured the evening best with his introduction. We are gathered here tonight to express the French government’s recognition of one of the most influential figures in American music, an outstanding artist, in one word: a visionary. I want to stress how important your work has been for both the American and the French. I want to put the emphasis on the main values and concerns that we all share: the importance of education and transmission of culture from one generation to the other, and a true commitment to the profoundly democratic idea that lies in jazz music. I strongly believe that, for you, jazz is more than just a musical form. It is tradition, it is part of American history and culture and life. To you, jazz is the sound of democracy. And from this democratic nature of jazz derives openness, generosity, and universality. Jazz at Lincoln Center. In 1987 Wynton Marsalis co-founded a jazz program at Lincoln Center. In July 1996, due to its significant success, Jazz at Lincoln Center (JALC) was installed as a new constituent of Lincoln Center, equal in stature with the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera, and New York City Ballet – a historic moment for jazz as an art form and for Lincoln Center as a cultural institution. In October 2004, with the assistance of a dedicated Board and staff, Marsalis opened Frederick P. Rose Hall, the world’s first institution for jazz. The complex contains three state-of-the-art performance spaces (including the first concert hall designed specifically for jazz) along with recording, broadcast, rehearsal and educational facilities. Jazz at Lincoln Center has become a preferred venue for New York jazz fans and a destination for travelers from throughout the world. Wynton presently serves as Managing and Artistic Director for Jazz at Lincoln Center. Under his leadership Jazz at Lincoln Center has developed an international agenda presenting rich and diverse programming that includes concerts, debates, film forums, dances, television and radio broadcasts, and educational activities. The JALC mission is to entertain, enrich and expand a global community for jazz through performance, education and advocacy, and to bolster the cultural infrastructure for jazz globally. Jazz at Lincoln Center has become a mecca for learning as well as a hub for performance. Their comprehensive educational programming includes a Band Director’s Academy, a hugely popular concert series for kids called Jazz for Young People, Jazz in the Schools, a Middle School Jazz Academy, WeBop! (for kids ages 8 months to 5 years), an annual High School Jazz Band Competition & Festival that reaches over 2000 bands in 50 states and Canada. In 2009 Wynton created and presented Ballad of the American Arts before a capacity crowd at the Kennedy Center. The lecture/performance was written to elucidate the essential role the arts have played in establishing America’s cultural identity. “This is our story, this is our song, ” states Marsalis, and if well sung, it tells us who we are and where we belong. In 2011 Harvard University President Drew Faust invited Wynton to enrich the cultural life of the University community. Wynton responded by creating a 6 lecture series which he delivered over the ensuing 3 years entitled Hidden In Plain View: Meanings in American Music, with the goal of fostering a stronger appreciation for the arts and a higher level of cultural literacy in academia. From 2015 to 2021 Wynton will serve as an A. White Professor at Cornell University. White Professors are charged with the mandate to enliven the intellectual and cultural lives of university students. Wynton Marsalis has devoted his life to uplifting populations worldwide with the egalitarian spirit of jazz. And while his body of work is enough to fill two lifetimes, Wynton continues to work tirelessly to contribute even more to our world’s cultural landscape. It has been said that he is an artist for whom greatness is not just possible, but inevitable. The most extraordinary dimension of Wynton Marsalis, however, is not his accomplishments but his character. It is the lesser-known part of this man who finds endless ways to give of himself. It is the person who waited in an empty parking lot for one full hour after a concert in Baltimore, waiting for a single student to return from home with his horn for a trumpet lesson. It is the citizen who personally funds scholarships for students and covers medical expenses for those in need. At the same time, he assumed a leadership role on the Bring Back New Orleans Cultural Commission where he was instrumental in shaping a master plan that would revitalize the city’s cultural base. From My Sister’s Place (a shelter for battered women) to Graham Windham (a shelter for homeless children), the Children’s Defense Fund, Amnesty International, the Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute, Food For All Seasons (a food bank for the elderly and disadvantaged), Very Special Arts (an organization that provides experiences in dance, drama, literature, and music for individuals with physical and mental disabilities) to the Newark Boys Chorus School (a full-time academic music school for disadvantaged youths), the Hugs Foundation (Help Us Give Smiles – provides free life changing surgical procedures for children with microtia, cleft lip and other facial deformities) and many, many more – Wynton responded enthusiastically to the call for service. It is Wynton Marsalis’ commitment to the improvement of life for all people that portrays the best of his character and humanity. Brown University (Doctor of Music, 1988). Southern University at New Orleans (Doctor of Music, 1988). University at Buffalo – State University of New York (Doctor of Music, 1990). Boston University (Doctor of Music, 1992). Academy of Southern Arts & Letters (Doctor of Philosophy in Arts, 1993). University of Miami (Doctor of Music, 1994). Hunter College (Doctor of Humane Letters, 1995). Manhattan School of Music (Doctor of Music, 1995). Princeton University (Doctor of Arts, 1995). Yale University (Doctor of Music, 1995). Royal Academy of Music (Honorary Member, 1996). Brandeis University (Doctor of Humane Letters, 1996). Columbia University (Doctor of Music, 1996). Governors State University (Doctor of Humane Letters, 1996). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Doctor of Fine Arts, 1996). University of Scranton (Doctor of Fine Arts, 1996). Amherst College (Doctor of Music, 1997). Howard University (Doctor of Music, 1997). Long Island University (Doctor of Music, 1997). Rutgers University (Doctor of Fine Arts, 1997). Bard College (Doctor of Fine Arts, 1998). Haverford College (Doctor of Humane Letters, 1998). University of Massachusetts Amherst (Doctor of Fine Arts, 1998). Middlebury College (Doctor of Arts, 2000). University of Pennsylvania (Doctor of Music, 2000). Clark Atlanta University (Doctor of Humane Letters, 2001). Connecticut College (Doctor of Fine Arts, 2001). Bloomfield College (Doctor of Fine Arts, 2004). Julliard School of Music (Doctor of Music, 2006). Denison University (Doctor of Music, 2006). New York University (Doctor of Fine Arts, 2007). Harvard University (Doctor of Music, 2009). Northwestern University (Doctor of Arts, 2009). State University of New York at Potsdam (Doctor of Music, 2010). The College of New Rochelle (Doctor of Humane Letters, 2011). Tulane University (Doctor of Humane Letters, 2014). Hunter College (President’s Medal, 2014). University Jean Moulin Lyon3 (Doctor Honoris Causa, 2016). Kenyon College (Doctor of Arts, 2019). Wynton Learson Marsalis (born October 18, 1961) is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Marsalis has won at least nine Grammy Awards, and his Blood on the Fields was the first jazz composition to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music. He is the only musician to win a Grammy Award in jazz and classical during the same year. Marsalis was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, on October 18, 1961 and grew up in the suburb of Kenner. [1] He is the second of six sons born to Dolores Ferdinand Marsalis and Ellis Marsalis Jr. A pianist and music teacher. [2] He was named for jazz pianist Wynton Kelly. [3] Branford Marsalis is his older brother and Jason Marsalis and Delfeayo Marsalis are younger. All three are jazz musicians. [4] While sitting at a table with trumpeters Al Hirt, Miles Davis, and Clark Terry, his father jokingly suggested that he might as well get Wynton a trumpet, too. Hirt volunteered to give him one, so at the age of six Marsalis received his first trumpet. Although he owned a trumpet when he was six, he did not practice much until he was 12. [1] He attended Benjamin Franklin High School and the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. [6][7] He studied classical music at school and jazz at home with his father. He played in funk bands and a marching band led by Danny Barker. He performed on trumpet publicly as the only black musician in the New Orleans Civic Orchestra. After winning a music contest at fourteen, he performed a trumpet concerto by Joseph Haydn with the New Orleans Philharmonic. Two years later he performed Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major by Bach. [5] At seventeen, he was the youngest musician admitted to Tanglewood Music Center. Marsalis reaching toward the camera. Marsalis backstage in 2007. In 1979, he moved to New York City to attend Juilliard. He intended to pursue a career in classical music. In 1980, he toured Europe as a member of the Art Blakey big band, becoming a member of The Jazz Messengers and remaining with Blakey until 1982. He changed his mind about his career and turned to jazz. He has said that years of playing with Blakey influenced his decision. [5] He recorded for the first time with Blakey and one year later he went on tour with Herbie Hancock. After signing a contract with Columbia, he recorded his first solo album. In 1982, he established a quintet with his brother Branford Marsalis, Kenny Kirkland, Charnett Moffett, and Jeff “Tain” Watts. When Branford and Kenny Kirkland left three years later to record and tour with Sting, Marsalis formed another quartet, this time with Marcus Roberts on piano, Robert Hurst on double bass, and Watts on drums. After a while, the band expanded to include Wessell Anderson, Wycliffe Gordon, Eric Reed, Herlin Riley, Reginald Veal, and Todd Williams. When asked about influences on his playing style, he cites Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Harry Sweets Edison, Clark Terry, Dizzy Gillespie, Jelly Roll Morton, Charlie Parker, Wayne Shorter, Thelonious Monk, Cootie Williams, Ray Nance, Maurice Andre, and Adolph Hofner. Marsalis at Lincoln Center in 2004. In 1987, Marsalis helped start the Classical Jazz summer concert series at Lincoln Center in New York City. [9] The success of the series led to Jazz at Lincoln Center becoming a department at Lincoln Center, [10] then to becoming an independent entity in 1996 with organizations such as the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera. [11] Marsalis became artistic director of the Center and the musical director of the band, the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. The orchestra performs at its home venue, Rose Hall, goes on tour, visits schools, appears on radio and television, and produces albums through its label, Blue Engine Records. In 2011, Marsalis and rock guitarist Eric Clapton performed together in a Jazz at Lincoln Center concert. The concert was recorded and released as the album Play the Blues: Live from Jazz at Lincoln Center. In 1986, Marsalis guest starred in an episode of Sesame Street. In 1995, he hosted the educational program Marsalis on Music on public television, while during the same year National Public Radio broadcast his series Making the Music. Both programs won the George Foster Peabody Award, the highest award given in journalism. In December 2011, Marsalis was named cultural correspondent for CBS This Morning. [12] He is a member of the CuriosityStream Advisory Board. [13] He serves as director of the Juilliard Jazz Studies program. In 2015, Cornell University appointed him A. Marsalis was involved in writing, arranging, and performing music for the 2019 Daniel Pritzker film Bolden. In The Jazz Book, the authors list what Marsalis considers to be the fundamentals of jazz: blues, standards, a swing beat, tonality, harmony, craftsmanship, and mastery of the tradition beginning with New Orleans jazz up to Ornette Coleman. He has little or no respect for free jazz, avant-garde, hip hop, fusion, European, or Asian jazz. Jazz critic Scott Yanow regards Marsalis as talented but criticizes his “selective knowledge of jazz history” and has said Marsalis considers “post-1965 avant-garde playing to be outside of jazz and 1970s fusion to be barren” and the unfortunate result of the “somewhat eccentric beliefs of Stanley Crouch”. [4] In The New York Times in 1997, pianist Keith Jarrett said Marsalis imitates other people’s styles too well… His music sounds like a high school trumpet player to me. Bassist Stanley Clarke said, All the guys that are criticizing – like Wynton Marsalis and those guys – I would hate to be around to hear those guys playing on top of a groove! ” But Clarke also said, “These things I’ve said about Wynton are my criticism of him, but the positive things I have to say about him outweigh the negative. He has brought respectability back to jazz. When he met Miles Davis, one of his idols, Davis said, So here’s the police… “[5] For his part, Marsalis compared Miles Davis’s embrace of pop music to “a general who has betrayed his country. “[5] He called rap “hormone driven pop music”[5] and said that hip hop “reinforces destructive behavior at home and influences the world’s view of the Afro American in a decidedly negative direction. Marsalis responded to criticism by saying, You can’t enter a battle and expect not to get hurt. “[5] He said that losing the freedom to criticize is “to accept mob rule, it is a step back towards slavery. Marsalis is the son of jazz musician Ellis Marsalis Jr. (pianist), grandson of Ellis Marsalis Sr. And brother of Branford (saxophonist), Delfeayo (trombonist), and Jason (drummer). Marsalis’s son, Jasper Armstrong Marsalis, is a music producer known professionally as Slauson Malone. Marsalis was raised Catholic. Marsalis received the National Medal of Arts from President George W. In 1983, at the age of 22, he became the only musician to win Grammy Awards in jazz and classical music during the same year. [5] At the award ceremonies the next year, he won again in both categories. After his first album came out in 1982, Marsalis won polls in DownBeat magazine for Musician of the Year, Best Trumpeter, and Album of the Year. In 2017, he was one of the youngest members to be inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame. In 1997, he became the first jazz musician to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his oratorio Blood on the Fields. In a note to him, Zarin Mehta wrote, I was not surprised at your winning the Pulitzer Prize for Blood on the Fields. It speaks to us all… I’m sure that, somewhere in the firmament, Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong and legions of others are smiling down on you. Wynton Marsalis has won the National Medal of Arts, the National Humanities Medal, [22] and been named an NEA Jazz Master. Statue dedicated to Wynton Marsalis in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. [24] He has toured in 30 countries and on every continent except Antarctica. He was given the Louis Armstrong Memorial Medal and the Algur H. He was inducted into the American Academy of Achievement[26] and was dubbed an Honorary Dreamer by the I Have a Dream Foundation. The New York Urban League awarded Marsalis the Frederick Douglass Medallion for distinguished leadership. The American Arts Council presented him with the Arts Education Award. He won the Dutch Edison Award and the French Grand Prix du Disque. The Mayor of Vitoria, Spain, gave him the city’s Gold Medal, its most coveted distinction. In 1996, Britain’s senior conservatoire, the Royal Academy of Music, made him an honorary member, the Academy’s highest decoration for a non-British citizen. The city of Marciac, France, erected a bronze statue in his honor for the key role he played in the story of the festival. The French Ministry of Culture gave him the rank of Knight in the Order of Arts and Literature. In 2008, he received France’s highest distinction, the insignia Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. He has received honorary degrees from the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami (1994), University of Scranton (1996), [28] Kenyon College (2019), New York University, [29] Columbia, Connecticut College, [30] Harvard, Howard, Northwestern, Princeton, Vermont, and the State University of New York. Best Jazz Instrumental Solo. Think of One (1983). Hot House Flowers (1984). Black Codes (From the Underground) (1985). Best Jazz Instrumental Album, Individual or Group. Marsalis Standard Time, Vol. Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra). Raymond Leppard (conductor), Wynton Marsalis and the National Philharmonic Orchestra for Haydn: Trumpet Concerto in E Flat/Leopold Mozart: Trumpet Concerto in D/Hummel: Trumpet Concerto in E Flat (1983). Raymond Leppard (conductor), Wynton Marsalis and the English Chamber Orchestra for Wynton Marsalis, Edita Gruberova: Handel, Purcell, Torelli, Fasch, Molter (1984). Best Spoken Word Album for Children. Listen to the Storytellers (2000). Main article: Wynton Marsalis discography. Sweet Swing Blues on the Road with Frank Stewart (1994). Marsalis on Music (1995). Jazz in the Bittersweet Blues of Life with Carl Vigeland (2002). To a Young Jazz Musician: Letters from the Road with Selwyn Seyfu Hinds (2004). Jazz ABZ: An A to Z Collection of Jazz Portraits with Paul Rogers (2007). Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life with Geoffrey Ward (2008). A Sonic Adventure with Paul Rogers (2012)[32]. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Autographs\Music”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, New Zealand, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Wallis and Futuna, Gambia, Malaysia, Taiwan, Poland, Oman, Suriname, United Arab Emirates, Kenya, Argentina, Guinea-Bissau, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Bhutan, Senegal, Togo, Ireland, Qatar, Burundi, Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, Equatorial Guinea, Thailand, Aruba, Sweden, Iceland, Macedonia, Belgium, Israel, Liechtenstein, Kuwait, Benin, Algeria, Antigua and Barbuda, Swaziland, Italy, Tanzania, Pakistan, Burkina Faso, Panama, Singapore, Kyrgyzstan, Switzerland, Djibouti, Chile, China, Mali, Botswana, Republic of Croatia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Portugal, Tajikistan, Vietnam, Malta, Cayman Islands, Paraguay, Saint Helena, Cyprus, Seychelles, Rwanda, Bangladesh, Australia, Austria, Sri Lanka, Gabon Republic, Zimbabwe, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Norway, Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Kiribati, Turkmenistan, Grenada, Greece, Haiti, Greenland, Yemen, Afghanistan, Montenegro, Mongolia, Nepal, Bahamas, Bahrain, United Kingdom, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, Angola, Western Samoa, France, Mozambique, Namibia, Peru, Denmark, Guatemala, Solomon Islands, Vatican City State, Sierra Leone, Nauru, Anguilla, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Cameroon, Guyana, Azerbaijan Republic, Macau, Georgia, Tonga, San Marino, Eritrea, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Morocco, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Mauritania, Belize, Philippines, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Colombia, Spain, Estonia, Bermuda, Montserrat, Zambia, South Korea, Vanuatu, Ecuador, Albania, Ethiopia, Monaco, Niger, Laos, Ghana, Cape Verde Islands, Moldova, Madagascar, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Lebanon, Liberia, Bolivia, Maldives, Gibraltar, Hong Kong, Central African Republic, Lesotho, Nigeria, Mauritius, Saint Lucia, Jordan, Guinea, Canada, Turks and Caicos Islands, Chad, Andorra, Romania, Costa Rica, India, Mexico, Serbia, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Lithuania, Trinidad and Tobago, Malawi, Nicaragua, Finland, Tunisia, Uganda, Luxembourg, Turkey, Germany, Egypt, Latvia, Jamaica, South Africa, Brunei Darussalam, Honduras.

- Industry: Music

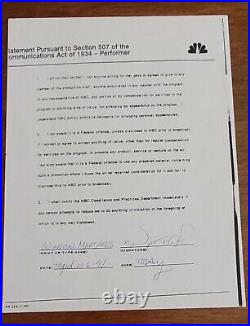

- Signed: Yes