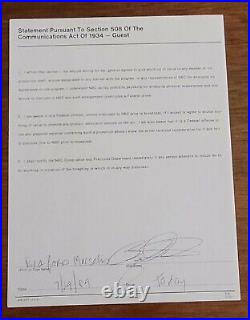

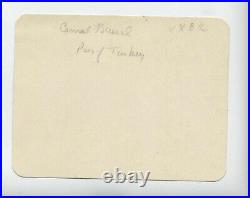

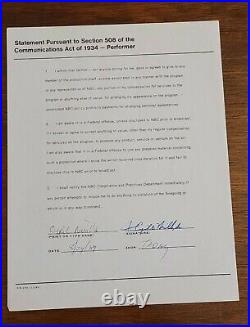

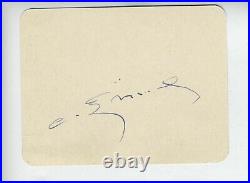

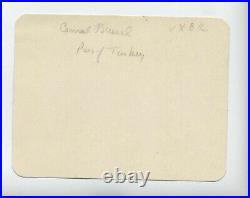

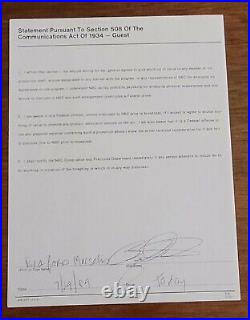

A GUEST CONTRACT FOR TODAY SHOW. SIGNED BY JAZZ LEGEND. ON 8.5X11 INCH PAPER. Branford Marsalis is an American saxophonist, composer, and bandleader. While primarily known for his work in jazz as the leader of the Branford Marsalis Quartet, he also performs frequently as a soloist with classical ensembles and has led the group Buckshot LeFonque. From 1992 to 1995 he led The Tonight Show Band. Branford Marsalis Biography (1960-). Born August 26, 1960, in New Orleans (some sources say Breaux Bridge), LA; son of Ellis (a jazz pianist and high school music teacher) and Delores (a jazzsinger and substitute teacher) Marsalis; brother of Wynton Marsalis (a composer and actor); married Teresa Reese (an actress), 1985 (divorced, 1994); children: Reese Ellis. Addresses: Manager: Wilkins Management, 323 Broadway, Cambridge, MA 02139. Contact: IMG Artist Worldwide, 825 Seventh Ave. 8th Floor, New York, NY 10019; 9520 Cedarbrook Dr. Beverly Hills, CA 90210. Musician, recording artist, actor. New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Host, Friday Night Videos, NBC, 1992. Bring on the Night (also known as Sting: Bring on the Night), 1985. Song performer, “Oleo, ” “I Thought about You, ” and “Giant Steps, ” Newport Jazz’87, PBS, 1987. Song performer, “502 Blues, ” Jacksonville Jazz Festival VII, PBS, 1987. Song performer, “I Mean You, ” Celebrating a Jazz Master: Thelonious Sphere Monk, PBS, 1987. Saxophone player, Sting in Tokyo, HBO, 1989. The 32nd Annual Grammy Awards, CBS, 1990. Victory and Valor: A Special Olympics All-Star Celebration, ABC, 1991. Story of a People: Expressions in Black, syndicated, 1991. Jazz at the Smithsonian: Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, 1991. The Music Tells You, 1992. Buddy Warren, “Without a Pass, ” Showtime Thirty-Minute Movie, Showtime, 1992. NBC Super Special All-Star Comedy Hour, NBC, 1993. Count on Me, PBS, 1993. The Best of Disney Music: A Legacy in Song–Part I, 1993. Narrator, Reed Royalty, Bravo, 1993. The Winans’ Real Meaning of Christmas, syndicated, 1993. 40 for the Ages: Sports Illustrated’s 40th Anniversary Special, NBC, 1994. Motown 40: The Music Is Forever (also known as Motown’s 40th: ARetrospective), ABC, 1998. Vince Gill Live by Request, Arts and Entertainment, 1999. Newport Jazz `99, PBS, 1999. Men Strike Back, VH1, 2000. Interviewee, Ellis Marsalis: Jazz is Spoken Here (documentary), PBS, 2000. (Uncredited) Interviewee, Added Attractions: The Hollywood Shorts Story (documentary), TCM, 2002. Late Night with David Letterman, 1985, 1988. The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, 1991. Himself, “The SAT Score Scam, ” Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? “Sleepless in Bel-Air, ” The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, NBC, 1994. In the Name of Love, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, NBC, 1993. “I Love This Game, ” Living Single, Fox, 1994. “Gum, Disease, ” Space Ghost Coast to Coast (animated), Cartoon Network, 1994. Late Show with David Letterman, 1995. Voice of the Frog Prince, Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child (animated), HBO, 1995. The Howard Stern Show, 1996. Hosted New Vision on VH1; appeared in Sesame Street, PBS; Evening at Pops, PBS; Sessions at West 54th, PBS. Music director, NBC Super Special All-Star Comedy Hour (special), NBC, 1993. Lester, Throw Momma from the Train, Orion, 1987. Jordan (Da Fellas), School Daze, Columbia, 1988. Saxophone player, Do the Right Thing, 1989. Party guest, Mo’ Better Blues, Universal, 1990. Saxophone player, Jazz at the Smithsonian: Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, 1990. Buddy Warren, Without a Pass, 1991. Branford Marsalis: The Music Tells You, 1992. Saxophone player, Malcolm X, Warner Bros. Harry Delacroix, Eve’s Bayou, Trimark Pictures, 1997. Host of JazzSet, National Public Radio. Scenes in the City, Columbia, 1984. Royal Garden Blues, Columbia, 1986. Random Abstract, Columbia, 1988. Trio Jeepy, Columbia, 1989. Crazy People Music, Columbia, 1990. The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born, Columbia, 1991. I Heard You Twice the First Time, Columbia, 1992. Dark Keys, Columbia, 1997. Contemporary Jazz, Columbia, 2000. (Contributor) Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Live at Montreux and Northsea, Timeless, 1980. (With father Ellis Marsalis) Fathers and Sons, Columbia, 1981. (With brother Wynton Marsalis) Wynton Marsalis, Columbia, 1982. Marsalis Think of One, Columbia, 1983. (With Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers) Keystone 3, Concord, 1983. (With Miles Davis) Decoy, Columbia, 1984. Marsalis Hot House Flowers, Columbia, 1984. (With Andy Jaffe) Manhattan Projections, Stash, 1984. (Contributor) Dizzie Gillespie, Closer to the Source, Atlantic, 1984. Marsalis Black Codes (from the Underground), Columbia, 1985. (With Sting) The Dream of The Blue Turtles, A&M, 1985. (Contributor) Dizzy Gillespie, New Faces, GRP, 1985. (With Sting) Bring On the Night, A&M, 1985. (Contributor) Kevin Eubanks, Opening Night, GRP, 1985. (With English Chamber Orchestra) Romances for Saxophone, Columbia, 1986. (Contributor) Teena Marie, Emerald City, Epic, 1986. (Contributor) Tina Turner, Break Every Rule, Capitol, 1986. (With Duke Ellington Brass Band Orchestra) “Cottontail, ” on Digital Duke, GRP, 1987. (With Sting) Nothing Like the Sun, A&M, 1987. (Contributor) School Daze (soundtrack recording), 1988. Music from Mo’ Better Blues, Sony, 1990. (With Sting) The Soul Cages, A&M, 1991. (Contributor) Weird Nightmare: Meditations on Mingus, Columbia, 1992. (Contributor) Guru, Jazzmatazz, Chrysalis/Capitol, 1993. (With Buckshot Le Fonque) Buckshot Lefonque, Sony/Columbia, c. (Contributor) Bela Fleck and the Fleckstones, Live Art, Warner Bros. (With Sting) Mercury Falling, A&M, 1996. (With Buckshot Le Fonque) Music Evolution, Sony, 1997. (Contributor) The Beautiful Thing, Verve, 1997. (Contributor) Jackies Blue Bag, Hip Bop Essence, 1997. Also recorded “Barcelona Mona” with Bruce Hornsby. Saxophone player, “We’ve Already Said Goodbye (Before We Said Hello), ” School Daze, Columbia, 1988. Song performer, “Lament, ” Sea of Love, 1989. Music performer, The Russia House, 1990. Song performer, “Knocked out of the Box, ” Lonely Woman, ” “Jazz Thing, ” Say Hey, ” “Beneath the Underdog, ” “Mo’ Better Blues, ” “Harlem Blues, ” and “Again Never, ” Mo’ Better Blues, Universal, 1990. Music performer, Mo’ Better Blues, Universal, 1990. Music performer, Psalms from the Underground, 1995. Once in the Life, 2000. Musician, David and Goliath, Rabbit Ears, 1993. Songs, “Larry’s Song” and “The Hallowed Tales of Delfbear, ” Throw Momma from the Train, Orion, 1987. Songs, “Say Hey, ” “Beneath the Underdog, ” “Pop Top 40, ” and “Knocked outof the Box, ” Mo’ Better Blues, Universal, 1990. Without a Pass, 1991. (Contributor) Branford Marsalis: The Music Tells You, 1992. (Contributor) Black to the Promised Land, 1992. To My Daughter with Love, 1994. M’sieurs dames, 1997. Once in the Life, Lions Gate, 2000. “Murder in Metropolis, ” “Without A Pass, ” Showtime Thirty-Minute Movie, Showtime, 1992. To My Daughter with Love (also known as Single Dad), NBC, 1994. Newton Story, Black Starz! Theme music, Temporarily Yours, CBS, 1997. Composer of numerous songs, including “No Backstage Pass, ” “Solstice, ” and Waiting for Rain. “As Ye Sow, ” Tales from the Crypt (also known as HBO’s Tales from the Crypt), 1989. Down Beat, March, 1987, p. 16; September, 1989, p. 94; November, 1989, p. 16; January, 1992, p. Ebony, February, 1989, p. Entertainment Weekly, May 2, 1997, p. Esquire, June, 1992, p. Gentleman’s Quarterly, May, 1991, p. New York, October 14, 1991, pp. New York Times Magazine, May 3, 1992, pp. Rolling Stone, February 25, 1988, p. Vogue, November, 1990, p. AFTER FOUR DECADES IN THE INTERNATIONAL SPOTLIGHT, THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF SAXOPHONIST BRANFORD MARSALIS CONTINUE TO GROW. After four decades in the international spotlight, the achievements of saxophonist Branford Marsalis continue to grow. From his initial recognition as a young jazz lion, he has expanded his vision as an instrumentalist, composer, bandleader and educator, crossing stylistic boundaries while maintaining an unwavering creative integrity. In the process, he has become a multi award-winning artist with three Grammys, a citation by the National Endowment for the Arts as a Jazz Master and an avatar of contemporary artistic excellence. Growing up in the rich environment of New Orleans as the oldest son of pianist and educator, the late Ellis Marsalis, Branford was drawn to music along with siblings Wynton, Delfeayo and Jason. The Branford Marsalis Quartet, formed in 1986, remains his primary means of expression. In its virtually uninterrupted three-plus decades of existence, the Quartet has established a rare breadth of stylistic range as demonstrated on the band’s latest release: The Secret Between the Shadow and the Soul. But Branford has not confined his music to the jazz quartet context. A frequent soloist with classical ensembles, Branford has become increasingly sought after as a featured soloist with acclaimed orchestras around the world, performing works by composers such as Copeland, Debussy, Glazunov, Ibert, Mahler, Milhaud, Rorem, Vaughan Williams and Villa-Lobos. And his legendary guest performances with the Grateful Dead and collaborations with Sting have made him a fan favorite in the pop arena. His work on Broadway has garnered a Drama Desk Award and Tony nominations for the acclaimed revivals of Children of a Lesser God, Fences, and A Raisin in the Sun. His screen credits include original music composed for: Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks starring Oprah Winfrey and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom starring Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman. Ma Rainey is the Netflix film adaptation of two-time Pulitzer Prize winner August Wilson’s play, produced by Denzel Washington and released in December 2020. Branford has also shared his knowledge as an educator, forming extended teaching relationships at Michigan State, San Francisco State and North Carolina Central Universities and conducting workshops at sites throughout the United States and the world. After the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina, Branford, along with friend Harry Connick, Jr. Conceived of “Musicians’ Village, ” a residential community in the Upper Ninth Ward of New Orleans. The centerpiece of the Village is the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music, honoring Branford’s father. The Center uses music as the focal point of a holistic strategy to build a healthy community and to deliver a broad range of services to underserved children, youth and musicians from neighborhoods battling poverty and social injustice. Branford Marsalis (born August 26, 1960) is an American saxophonist, composer, and bandleader. Classical and Broadway projects: 2008-10. As sideman or guest. Marsalis was born in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana. He is the son of Dolores (née Ferdinand), a jazz singer and substitute teacher, and Ellis Louis Marsalis, Jr. A pianist and music professor. [1][2] His brothers Jason Marsalis, Wynton Marsalis, and Delfeayo Marsalis are also jazz musicians. In mid-1980, while still a Berklee College of Music student, Marsalis toured Europe playing alto and baritone saxophone in a large ensemble led by drummer Art Blakey. Other big band experiences with Lionel Hampton and Clark Terry followed over the next year, and by the end of 1981 Marsalis, on alto saxophone, had joined his brother Wynton in Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. Other performances with his brother, including a 1981 Japanese tour with Herbie Hancock, led to the formation of his brother Wynton’s first quintet, where Marsalis shifted his emphasis to soprano and tenor saxophones. He continued to work with Wynton until 1985, a period that also saw the release of his own first recording, Scenes in the City, as well as guest appearances with other artists including Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. Branford Marsalis at Monterey Jazz Festival 1992. In 1985, he joined Sting, singer and bassist of rock band the Police, on his first solo project, The Dream of the Blue Turtles, alongside jazz and session musicians Omar Hakim on drums, Darryl Jones on the bass and Kenny Kirkland on keyboards. He became a regular in Sting’s line-up both in the studio and live up until the release of Brand New Day in 1999. In 1986, Marsalis formed the Branford Marsalis Quartet with pianist Kirkland, drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts and bass player Robert Hurst. That year, they released their first album, Royal Garden Blues. That lineup of the quartet would go on to release four more albums, the last of which, I Heard You Twice the First Time (1992), won the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Jazz Album, Individual or Group. In 1988, Marsalis co-starred in the Spike Lee film School Daze, also rendering several horn-blowing interludes for the music in the film. His witty comments have pegged him to many memorable one-liners in the film. In 1989, Marsalis played a 30 second cover of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” over the opening logos of Lee’s film Do the Right Thing. Between 1990 and 1994, Branford played with the Grateful Dead numerous times, and appeared on their 1990 live album Without a Net. In 1992, Marsalis became the leader of the Tonight Show Band on the newly-launched The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, after Jay Leno replaced Johnny Carson. Initially, Marsalis turned down the offer, but later reconsidered and accepted the position. He brought with him the three other members of the Branford Marsalis Quartet, who became the Tonight Show Band’s pianist, drummer and bass player, respectively. In 1994, Marsalis formed the group Buckshot LeFonque (named after a pseudonym once used by Cannonball Adderley), a jazz group with elements of rock and hip-hop. That year, they released their first album, Buckshot LeFonque, which was mostly produced by DJ Premier. In 1994, Marsalis appeared on the Red Hot Organization’s compilation CD, Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool. [3] The album, meant to raise awareness of the AIDS epidemic in African American society, was named Album of the Year by Time. In 1995, Marsalis left The Tonight Show, having become unhappy in the role: he disliked that he was supposed to always show enthusiasm, even for jokes he thought were unfunny. He was succeeded as bandleader by guitarist Kevin Eubanks. In a well-publicized interview soon after leaving, Marsalis said, The job of musical director I found out later was just to kiss the ass of the host, and I ain’t no ass kisser. ” He also complained that when he did not laugh or smile, some viewers’ perception was, “Oh, he’s surly. He hates his boss. ” When the interviewer asked if Marsalis did hate Leno, Marsalis responded, “Oh, I despised him. ” He later stated that he did not hate Leno, and that this was a sarcastic response to what he considered “a ridiculous question. In 1997, bassist Eric Revis replaced Hurst in the Branford Marsalis Quartet. Kirkland died the following year, and was replaced by pianist Joey Calderazzo. The Branford Marsalis Quartet has since toured and recorded extensively. For two decades Marsalis was associated with Columbia, where he served as creative consultant and producer for jazz recordings between 1997 and 2001, including signing saxophonist David S. Ware for two albums. In 2002, Marsalis founded his own label, Marsalis Music. Its catalogue includes Claudia Acuña, Harry Connick Jr. Doug Wamble, Miguel Zenón, in addition to albums by members of the Marsalis family. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Marsalis and Harry Connick, Jr. Working with the local Habitat for Humanity, created Musicians Village in New Orleans, with the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music the centerpiece. Under the direction of conductor Gil Jardim, Branford Marsalis and members of the Philharmonia Brasileira toured the United States in the fall of 2008, performing works by Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos, arranged for solo saxophone and orchestra. This project commemorated the 50th Anniversary of the revered Brazilian composer s death. Marsalis and the members of his quartet joined the North Carolina Symphony for American Spectrum, released in February 2009 by Sweden’s BIS Records. The album showcases Marsalis and the orchestra performing a range of American music by Michael Daugherty, John Williams, Ned Rorem and Christopher Rouse, while being conducted by Grant Llewellyn. Marsalis wrote the music for the 2010 Broadway revival of the August Wilson play Fences. On July 14, 2010, Marsalis made his debut with the New York Philharmonic on Central Park’s Great Lawn. Led by conductor Andrey Boreyko, Marsalis and the New York Philharmonic performed Glazunov’s “Concerto for Alto Saxophone” and Schuloff’s Hot-Sonate for Alto Saxophone and Orchestra. Boreyko, Marsalis and the Philharmonic performed the same program again in Vail, CO later that month and four more times at Avery Fisher Hall in New York, NY the following February. Branford Marsalis at a concert in Bielsko-Biala, Poland at the Lotos Jazz Festival 2019. In June 2011, after working together for over 10 years in a band setting, Branford Marsalis and Joey Calderazzo released their first duo album titled Songs of Mirth and Melancholy, on Branford’s label, Marsalis Music. Their first public performance was at the 2011 TD Toronto Jazz Festival. In 2012, Branford Marsalis released Four MFs Playin’ Tunes on deluxe 180-gram high definition vinyl, prior to Record Store Day 2012 on April 21, 2012. This is the first recording of the Branford Marsalis Quartet with drummer Justin Faulkner, who joined the band in 2009, and was the first vinyl release from Marsalis Music. The album was named Apple iTunes Best of 2012 Instrumental Jazz Album of the Year. Marsalis performed “The Star-Spangled Banner” on Wednesday, September 5, 2012 at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte. In 2019 Marsalis released The Secret Between the Shadow and the Soul, which he recorded in Australia with his quartet. Marsalis, commenting on the longevity of his band and their approach said, ahead of the album’s release:’Staying together allows us to play adventurous, sophisticated music and sound good. Lack of familiarity leads to defensive playing, playing not to make a mistake. I like playing sophisticated music, and I couldn’t create this music with people I don’t know. Marsalis was raised Catholic. The Branford Marsalis Quartet received a Grammy Award in 2001 for their album Contemporary Jazz. In September 2006, Branford Marsalis was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music. During his acceptance ceremony, he was honored with a tribute performance featuring music throughout his career. Marsalis won the 2010 Drama Desk Award in the category “Outstanding Music in a Play” and was also nominated for a 2010 Tony Award in the category of “Best Original Score (Music and/or Lyrics) Written for the Theatre” for his participation in the Broadway revival of August Wilson’s Fences. Marsalis, with his father and brothers, were group recipients of the 2011 NEA Jazz Masters Award. In May 2012, he received an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In June 2012, Marsalis, along with friend and fellow New Orleans native Harry Connick, Jr. Roger Horchow Award for Greatest Public Service by a Private Citizen, an award given out annually by the Jefferson Awards for Public Service, for their work in the Musicians’ Village of New Orleans. On March 26, 2013, he received the degree of Doctor of Arts Leadership, honoris causa from Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota. Soprano: His most famous soprano has been a silver Selmer Mark VI with a modified bent neck. He is said[13] to now be playing a Yamaha YSS-82ZR, and uses a Selmer D mouthpiece and Vandoren V12 Clarinet reeds 5+[14]. Alto: Cannonball Vintage Series (model AV/LG-L)[15] with a Selmer Classic C mouthpiece and Vandoren #5[14]. Tenor: Selmer Super Balanced Action with a Fred Lebayle 8 mouthpiece and Alexander Superial size 3.5 reeds[14]. Marsalis performed alongside Sting and Phil Collins at the London Live Aid concert at Wembley Stadium on July 13, 1985. Featured as saxophonist on “Fight the Power” (1989) by Public Enemy. Don’t Tell Me! Guest on the “Not My Job” section of the show. On this performance he claimed the saxophone was the sexiest instrument, then insults the accordion. In a later episode of the show, “Weird Al” Yankovic stands up for the accordion; later guest Yo-Yo Ma claimed the saxophone was in fact the sexiest. Interviewed on Space Ghost Coast to Coast Episode 10: “Gum, Disease” (aired November 11, 1994). Although the Coast to Coast crew said, “He was the most pleasant, and well mannered guest we had ever interviewed”, he didn’t sign a release for merchandising rights, so the episode couldn’t be on the Space Ghost Coast to Coast Volume One DVD. Marsalis was featured in Shanice’s 1992 hit “I Love Your Smile”. In the second half of the song, he has a solo and Shanice says, “Blow, Branford, Blow”. He played the role of Lester in the movie Throw Momma from the Train (1987) and the role of Jordam in Spike Lee’s 1988 musical-drama film School Daze. Cameo as a repair man who asks Hillary on a date in the episode Stop Will! In the Name of Love”, and as himself in the episode “Sleepless in Bel-Air on the sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (1994). Interviews with Marsalis are featured prominently in the documentary Before the Music Dies (2006). Marsalis was a guest judge on the final episode of the fifth season of Top Chef which took place in New Orleans, Louisiana. On April 28 and 29, 2009, Marsalis played with the Dead (the remaining members of the Grateful Dead) at the IZOD Center in East Rutherford, New Jersey, rekindling a relationship started when he performed with them at a set at Nassau Coliseum on March 29, 1990, [16] during which, according to Dead aficionados, who? One of the greatest renditions of “Eyes of the World”, was performed. On July 21, 2010, Marsalis guested with Dave Matthews Band on the songs “Lover Lay Down, ” “What Would You Say” and “Jimi Thing” at the Verizon Wireless Amphitheater in Charlotte, NC. This was the first time Marsalis had guested with Dave Matthews Band, although he had previously played with Dave Matthews and Gov’t Mule on a cover of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” on December 16, 2006 in Asheville, NC. [17] Marsalis performed with the Dave Matthews Band again on December 12, 2012 at the PNC Arena in Raleigh, NC. Marsalis appeared as a special guest of Bob Weir and Bruce Hornsby at two festivals in the summer of 2012. They first performed at the All Good Music Festival in Thornville, OH on July 19, 2012 and then headed to Bridgeport, CT for a performance at Gathering of the Vibes the following day, July 20, 2012. Marsalis appeared as a special guest of Furthur for their performance at Red Rocks on September 21, 2013. Marsalis appeared as a special guest of Dead & Company for their second night of a two night headlining performance at Lock’n Festival on August 26, 2018. 1982 Fathers & Sons with Wynton Marsalis, Ellis Marsalis, Chico Freeman, Von Freeman (Columbia). 1984 Scenes in the City (Columbia). 1986 Romances for Saxophone (CBS Masterworks). 1986 Royal Garden Blues (CBS). 1988 Random Abstract (CBS). 1989 Trio Jeepy (CBS). 1990 Crazy People Music. 1990 Mo’ Better Blues. 1991 The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born. 1991 Herve Sellin Sextet/Brandford Marsalis (Columbia). 1992 I Heard You Twice the First Time (Columbia). 1992 David and Goliath (Rabbit Ears). 1996 The Dark Keys. 1996 Loved Ones with Ellis Marsalis (Columbia). 2001 Creation with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra (Sony Classical). 2002 Footsteps of Our Fathers. 2003 Romare Bearden Revealed. 2009 American Spectrum (BIS). 2011 Songs of Mirth and Melancholy with Joey Calderazzo (Marsalis Music). 2012 Four MFs Playin’ Tunes (Marsalis Music). 2013 Romances for Saxophone (Sony Music). 2014 In My Solitude: Live at Grace Cathedral (Marsalis Music). 2016 Upward Spiral (Marsalis Music) with Kurt Elling. 2019 The Secret Between the Shadow and the Soul (Sony Masterworks). Live at Montreux and Northsea (Timeless, 1981). Keystone 3 (Concord Jazz, 1982). Terence Blanchard (Columbia, 1991). Malcolm X (Columbia, 1992). Wandering Moon (Sony Classical, 2000). In the Door (Blue Note, 1991). To Know One (Blue Note, 1992). Going Home (Sunnyside, 2015). With Harry Connick Jr. We Are in Love (Columbia, 1990). Songs I Heard (Columbia, 2001). Occasion: Connick on Piano, Volume 2 (Marsalis Music/Rounder, 2005). Your Songs (Columbia, 2009). Smokey Mary (Columbia, 2013). Every Man Should Know (Columbia, 2013). Three Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest Warner Bros. Tales from the Acoustic Planet Warner Bros. Live Art Warner Bros. Little Worlds (Columbia, 2003). Closer to the Source (Atlantic, 1984). New Faces (GRP, 1985). Without a Net (Arista, 1990). Spring 1990 (The Other One) (2014). Wake Up to Find Out (Rhino, 2014). The Vibe (Novus, 1992). With the Tenors of Our Time (Verve, 1994). With Anna Maria Jopek. Pontius Pilate’s Decision (Novus, 1992). Minions Domain (Troubadour, 2006). With Ellis Marsalis Jr. Whistle Stop (CBS, 1994). Loved Ones (Columbia, 1996). Pure Pleasure for the Piano (Verve, 2012). Wynton Marsalis (Columbia, 1982). Think of One (CBS, 1983). Hot House Flowers (Columbia, 1984). Black Codes (From the Underground) (Columbia, 1985). Joe Cool’s Blues (Columbia, 1995). Jump Start and Jazz (Sony Classical, 1997). Love Stories (Columbia, 2000). A New Beginning (Boobescoot, 2010). The Dream of the Blue Turtles (A&M, 1985). Bring On the Night (A&M, 1986). Nothing Like the Sun (A&M, 1987). The Soul Cages (A&M, 1991). Mercury Falling (A&M, 1996). Brand New Day (A&M, 1999). Live in Berlin (Deutsche Grammophon 2010). New Moon Shine (Columbia, 1991). Country Libations (Marsalis Music, 2003). Bluestate (Marsalis Music, 2005). With Jeff “Tain” Watts. Citizen Tain (Columbia, 1999). Watts (Dark Key Music, 2009). Roy Ayers, You Might Be Surprised (Columbia, 1985). Allman Brothers, Cream of the Crop (Peach, 2018). Victor Bailey, Bottom’s Up (Atlantic, 1989). Joanne Brackeen, Fi-Fi Goes to Heaven (Concord Jazz, 1987). Alex Bugnon, As Promised (Narada/Virgin 2000). Mary Chapin Carpenter, Stones in the Road (Columbia, 1994). Dori Caymmi, Kicking Cans (Qwest, 1993). Ornette Coleman, Celebrate Ornette (Song X, 2016). Steve Coleman, Sine Die (Pangaea, 1988). Crosby, Stills & Nash, Live It Up (1990). Miles Davis, Decoy (Columbia, 1984). Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Voodoo (Columbia, 1989). Ray Drummond, Susanita (Nilva 1984). Kurt Elling, The Questions (Okeh, 2018). Kevin Eubanks, Opening Night (GRP, 1985). Robin Eubanks, Karma (JMT, 1991). Charles Fambrough, The Proper Angle (CTI, 1991). Benny Golson, Tenor Legacy (Arkadia Jazz, 1998). Paul Grabowsky, Tales Of Time And Space (Sanctuary Records, 2005). Dave Grusin, Migration (GRP, 1989). Russell Gunn, Young Gunn Plus (32 Jazz, 1998). Charlie Haden, Dream Keeper (DIW, 1990). Everette Harp, Common Ground (Blue Note/Contemporary, 1993). Billy Hart, Oshumare (Gramavision, 1984). Shirley Horn, You Won’t Forget Me (Verve, 1991). James Horner, Sneakers (Columbia, 1992). Bruce Hornsby, Harbor Lights (RCA, 1993). Robert Hurst, Robert Hurst Presents: Robert Hurst (Columbia, 1993). Bobby Hutcherson, Good Bait (Landmark, 1985). Miles Jaye, Miles (Island, 1987). Carole King, City Streets (Capitol, 1989). Kenny Kirkland, Kenny Kirkland (GRP, 1991). Bill Lee, Do the Right Thing (CBS, 1989). Michael McDonald, Wide Open (BMG, 2017). Marcus Miller, M2 (Victor, 2001). Youssou N’Dour, The Guide (Columbia 1994). Neville Brothers, Uptown (EMI, 1987). Ivan Neville, Thanks (Iguana, 1995). Makoto Ozone, The Trio (Verve, 2000). John Patitucci, Communion (Concord Jazz, 2001). Courtney Pine, The Vision’s Tale (Antilles). Eric Revis, In Memory of Things Yet Seen (Clean Feed, 2014). Sonny Rollins, Falling in Love with Jazz (Milestone, 1989). Renee Rosnes, Renee Rosnes (Blue Note, 1990). David Sanchez, Melaza (Columbia, 2000). Janis Siegel, At Home (Atlantic, 1987). Horace Silver, It’s Got to Be Funky (Columbia, 1993). Ed Thigpen, Young Men & Olds (Timeless, 1990). Tina Turner, Break Every Rule (Capitol, 1986). Chucho Valdes, Border-Free (Harmonia Mundi/JazzVillage 2013). Vinx, Rooms in My Fatha’s House I. Randy Waldman, Unreel (Concord Jazz, 2001). Joe Louis Walker, JLW (Verve, 1994). Was (Not Was), Born to Laugh at Tornadoes (Geffen, 1983). Rob Wasserman, Trios (GRP, 1994). Cleveland Watkiss, Blessing in Disguise (Polydor, 1991). Mark Whitfield, True Blue (Verve, 1994). Nancy Wilson, Forbidden Lover (CBS, 1993). Ben Wolfe, No Stranger Here (MAXJAZZ, 2008). Stevie Wonder, Conversation Peace (Motown, 1995). Branford Marsalis- The Soundillusionist. Germany 2016, 88 min. HD Stereo Language: English. Directed by Reinhold Jaretzky. Produced by Zauberbergfilm, Berlin, Germany. Living Single Season 2 cameo. Throw Momma From the Train (1987).