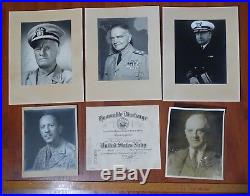

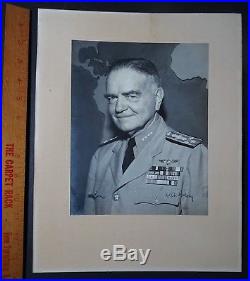

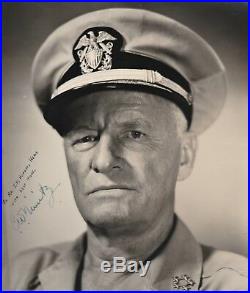

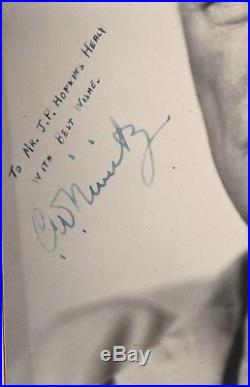

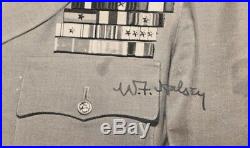

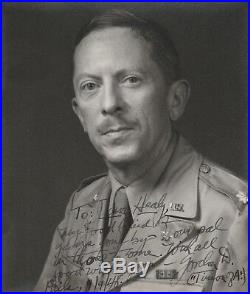

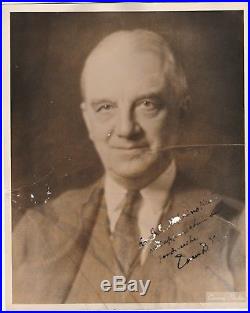

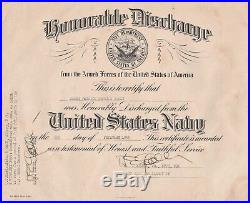

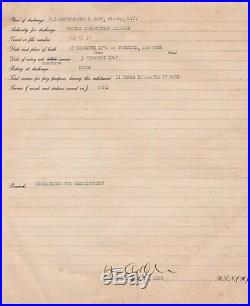

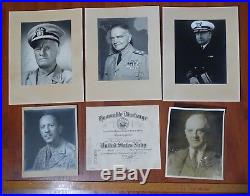

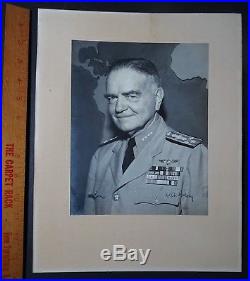

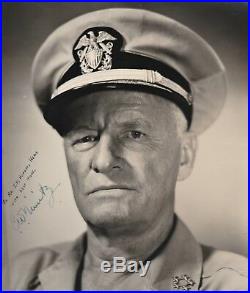

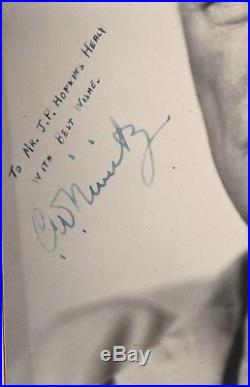

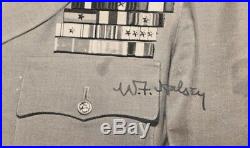

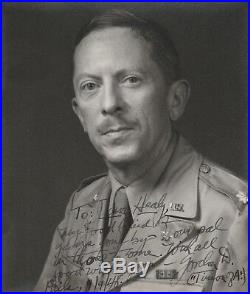

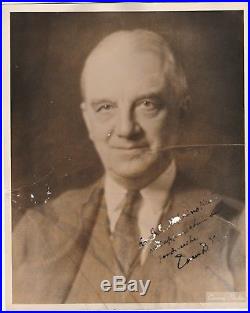

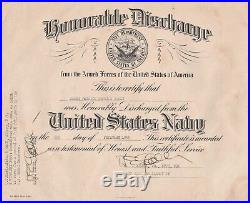

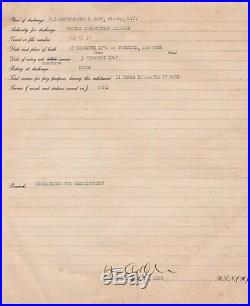

SUPER WWII Signed Photo Archive + MORE. Fresh from the Estate of a WWII Veteran. For offer – a very nice archive collection! Fresh from an estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now. Vintage, Old, antique, Original – NOT Reproductions – Guaranteed!! These pieces came out of an estate in Springwater, NY. 6 pieces, belonged to James Patrick Hopkins Healy, who was in the US Navy during WWII and discharged in 1955. Included are the following: Signed photo of Admiral C. Nimitz; Signed Photo of Fleet Admiral W. Halsey, 3 other photos I have not identified – one a Rear Admiral; Honorable Discharge of Healy, signed. Three photos are fairly large and high quality, as shown in photos. Overall in good to very good condition. The last photo – an 8 x 10, has some erosion of the inscription and signature. If you collect United States Military, 20th century history, American, Americana, photography images, autographs, etc. This is a nice one for your paper or ephemera collection. Chester William Nimitz, Sr. (/nmts/; February 24, 1885 February 20, 1966) was a fleet admiral of the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Fleet (CinCPac) and Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas (CinCPOA), commanding Allied air, land, and sea forces during World War II. Nimitz was the leading US Navy authority on submarines. Qualified in submarines during his early years, he later oversaw the conversion of these vessels’ propulsion from gasoline to diesel, and then later was key in acquiring approval to build the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Nautilus, whose propulsion system later completely superseded diesel-powered submarines in the US. He also, beginning in 1917, was the Navy’s leading developer of underway replenishment techniques, the tool which during the Pacific war would allow the US fleet to operate away from port almost indefinitely. The chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation in 1939, Nimitz served as Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) from 1945 until 1947. He was the United States’ last surviving officer who served in the rank of fleet admiral. Early life and education[edit]. Nimitz, a German Texan, was born the son of Anna Josephine (Henke) and Chester Bernhard Nimitz on February 24, 1885, in Fredericksburg, Texas, [3] where his grandfather’s hotel is now the Admiral Nimitz State Historic Site. His frail, rheumatic father had died six months earlier, on August 14, 1884. [4] He was significantly influenced by his German-born paternal grandfather, Charles Henry Nimitz, a former seaman in the German Merchant Marine, who taught him, the sea like life itself is a stern taskmaster. The best way to get along with either is to learn all you can, then do your best and don’t worry especially about things over which you have no control. [5] His grandfather became a Texas Ranger in the Texas Mounted Volunteers in 1851. He then served as captain of the Gillespie Rifles Company in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. Originally, Nimitz applied to West Point in hopes of becoming an Army officer, but no appointments were available. His congressman, James L. Slayden, told him that he had one appointment available for the United States Naval Academy and that he would award it to the best qualified candidate. Nimitz felt that this was his only opportunity for further education and spent extra time studying to earn the appointment. He was appointed to the United States Naval Academy from Texas’s 12th congressional district in 1901, and he graduated with distinction on January 30, 1905, seventh in a class of 114. This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). Midshipman 1/C Nimitz, circa 1905. Nimitz joined the battleship Ohio at San Francisco, and cruised on her to the Far East. In September 1906, he was transferred to the cruiser Baltimore; on January 31, 1907, after the two years at sea as a warrant officer then required by law, he was commissioned as an ensign. Remaining on Asiatic Station in 1907, he successively served on the gunboat Panay, destroyer Decatur, and cruiser Denver. The destroyer Decatur ran aground on a mud bank in the Philippines on July 7, 1908 while under the command of Ensign Nimitz. In May of that year, he was given command of the flotilla, with additional duty in command of USS Plunger, later renamed A-1. He commanded USS Snapper (later renamed C-5) when that submarine was commissioned on February 2, 1910, and on November 18, 1910 assumed command of USS Narwhal (later renamed D-1). In the latter command, he had additional duty from October 10, 1911 as Commander 3rd Submarine Division Atlantic Torpedo Fleet. In November 1911, he was ordered to the Boston Navy Yard, to assist in fitting out USS Skipjack and assumed command of that submarine, which had been renamed E-1, at her commissioning on February 14, 1912. On the monitor Tonopah on March 20, 1912, he rescued Fireman Second Class W. Walsh from drowning, receiving a Silver Lifesaving Medal for his action. World War I[edit]. In the summer of 1913, Nimitz (who spoke German) studied engines at the diesel engine plants in Nuremberg, Germany, and Ghent, Belgium. Returning to the New York Navy Yard, he became executive and engineer officer of Maumee at her commissioning on October 23, 1916. Navy destroyers to cross the Atlantic, to take part in the war. Under his supervision, Maumee conducted the first-ever underway refuelings. On August 10, 1917, Nimitz became aide to Rear Admiral Samuel S. Robison, Commander, Submarine Force, U. On February 6, 1918, Nimitz was appointed chief of staff and was awarded a Letter of Commendation for meritorious service as COMSUBLANT’s chief of staff. On September 16, he reported to the office of the Chief of Naval Operations, and on October 25 was given additional duty as Senior Member, Board of Submarine Design. Between the wars[edit]. From May 1919 to June 1920, he served as executive officer of the battleship South Carolina. He then commanded the cruiser Chicago with additional duty in command of Submarine Division 14, based at Pearl Harbor. Returning to the mainland in the summer of 1922, he studied at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island. In June 1923, he became aide and assistant chief of staff to the Commander, Battle Fleet, and later to the Commander In Chief, U. In August 1926, he went to the University of California, Berkeley, to establish the Navy’s first Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps unit. Nimitz lost part of one finger in an accident with a diesel engine, only saving the rest of it when the machine jammed against his Annapolis ring. In June 1929, he took command of Submarine Division 20. In June 1931, he assumed command of the destroyer tender Rigel and the destroyers out of commission at San Diego, California. In October 1933, he took command of the cruiser Augusta and deployed to the Far East, where in December, Augusta became the flagship of the Asiatic Fleet. He took command of Battleship Division 1, Battle Force. On June 15, 1939, he was appointed chief of the Bureau of Navigation. During this time, Nimitz conducted experiments in the underway refueling of large ships which would prove a key element in the Navy’s success in the war to come. World War II[edit]. (December 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). See also: United States Navy in World War II. Nimitz pins the Navy Cross on Doris “Dorie” Miller at ceremony on board USS Enterprise, Pearl Harbor, May 27, 1942. The surrender of Japan aboard USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945: Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, representing the United States, signs the instrument of surrender. Ten days after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he was promoted by Roosevelt to commander-in-chief, United States Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT), with the rank of admiral, effective December 31. The change of command ceremony would normally have taken place aboard a battleship, but every battleship in Pearl Harbor had been either sunk or damaged during the attack. Assuming command at the most critical period of the war in the Pacific, Admiral Nimitz successfully organized his forces to halt the Japanese advance despite the losses from the attack on Pearl Harbor and the shortage of ships, planes, and supplies. On March 24, 1942, the newly formed US-British Combined Chiefs of Staff issued a directive designating the Pacific theater an area of American strategic responsibility. Six days later, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) divided the theater into three areas: the Pacific Ocean Areas, the Southwest Pacific Area (commanded by General Douglas MacArthur), and the Southeast Pacific Area. The JCS designated Nimitz as “Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas”, with operational control over all Allied units (air, land, and sea) in that area. As rapidly as ships, men, and materiel became available, Nimitz shifted to the offensive and fought the Japanese navy in the Battle of the Coral Sea a tactical victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk, but a strategic victory for the Allies for several reasons in the pivotal Battle of Midway, and in the Solomon Islands campaign. The severe losses in carriers at Midway prevented the Japanese from re-attempting to invade Port Moresby from the ocean. The Allies took advantage of Japan’s resulting strategic vulnerability in the South Pacific and launched the Guadalcanal Campaign that, along with the New Guinea Campaign, eventually broke Japanese defenses in the South Pacific. In the final phases in the war in the Pacific, Nimitz’s forces attacked the Mariana Islands, inflicting a decisive defeat on the Japanese fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and capturing Saipan, Guam, and Tinian. His Fleet Forces isolated enemy-held bastions of the central and eastern Caroline Islands and secured in quick succession Peleliu, Angaur, and Ulithi. In the Philippines, his ships turned back powerful task forces of the Japanese fleet, a historic victory in the multiphased Battle of Leyte Gulf, October 24 to 26, 1944. Nimitz culminated his long-range strategy by successful amphibious assaults on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. In addition, Nimitz also ordered the United States Army Air Forces to mine the Japanese ports and waterways by air with B-29 Superfortresses in a successful mission called Operation Starvation, which severely interrupted the Japanese logistics. By Act of Congress, passed on December 14, 1944, the grade of Fleet Admiral the highest grade in the Navy was established and the next day President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Nimitz to that rank. Nimitz took the oath of that office on December 19, 1944. In January 1945, Nimitz moved the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet forward from Pearl Harbor to Guam for the remainder of the war. On September 2, 1945, Nimitz signed for the United States when Japan formally surrendered on board USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. On October 5, 1945, which had been officially designated as “Nimitz Day” in Washington, D. Admiral Nimitz was personally presented a Gold Star for the third award of the Distinguished Service Medal by Harry S. Truman for exceptionally meritorious service as Commander in Chief, U. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, from June 1944 to August 1945. On November 26, 1945, his nomination as Chief of Naval Operations was confirmed by the U. Senate, and on December 15, 1945, he relieved Fleet Admiral Ernest J. He had assured the President that he was willing to serve as the CNO for one two-year term, but no longer. He tackled the difficult task of reducing the most powerful navy in the world to a fraction of its war-time strength, while establishing and overseeing active and reserve fleets with the strength and readiness required to support national policy. For the postwar trial of German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946, Nimitz furnished an affidavit in support of the practice of unrestricted submarine warfare, a practice that he himself had employed throughout the war in the Pacific. This evidence is widely credited as a reason why Dönitz was sentenced to only 10 years of imprisonment. Nimitz endorsed an entirely new course for the U. Navy’s future by way of supporting then-Captain Hyman G. Rickover’s chain-of-command-circumventing proposal in 1947 to build USS Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear-powered vessel. [11] As is noted at a display at the Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, Texas: Nimitz’s greatest legacy as CNO is arguably his support of Admiral Hyman Rickover’s effort to convert the submarine fleet from diesel to nuclear propulsion. From 1949 to 1953, Nimitz served as UN-appointed Plebiscite Administrator for Jammu and Kashmir. [12] His proposed role as administrator was accepted by Pakistan but rejected by India. Inactive duty as a fleet admiral[edit]. On December 15, 1947, Nimitz retired from office as Chief of Naval Operations and received a third Gold Star in lieu of a fourth Navy Distinguished Service Medal. However, since the rank of fleet admiral is a lifetime appointment, he remained on active duty for the rest of his life, with full pay and benefits. He and his wife, Catherine, moved to Berkeley, California. After he suffered a serious fall in 1964, he and Catherine moved to US Naval quarters on Yerba Buena Island in the San Francisco Bay. In San Francisco, Nimitz served in the mostly ceremonial post as a special assistant to the Secretary of the Navy in the Western Sea Frontier. He worked to help restore goodwill with Japan after World War II by helping to raise funds for the restoration of the Japanese Imperial Navy battleship Mikasa, Admiral Heihachiro Togo’s flagship at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. He was also appointed as the United Nations Plebiscite Administrator for Kashmir, but owing to disagreements between India and Pakistan over demilitarization, that mission did not take place. Nimitz became a member of the Bohemian Club of San Francisco. In 1948, he sponsored a Bohemian dinner in honor of U. Army General Mark Clark, known for his campaigns in North Africa and Italy. Nimitz served as a regent of the University of California during 19481956, where he had formerly been a faculty member as a professor of naval science for the NROTC program. Nimitz was honored on October 17, 1964, by the University of California on Nimitz Day. Nimitz as he appears at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D. Nimitz married Catherine Vance Freeman (March 22, 1892 February 1, 1979) on April 9, 1913, in Wollaston, Massachusetts. Nimitz and his wife had four children. Catherine Vance “Kate” (22 February 1914, Brooklyn, NY 14 January 2015)[17][18]. Chester William “Chet”, Jr. Anna Elizabeth “Nancy” (19192003[20][21]). Mary Manson (19312006[22][23]). Catherine Vance graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1934, [24] became a music librarian with the Washington D. Public Library, [25] and married U. Navy Commander James Thomas Lay (19092001[26]), from St. Clair, Missouri, in Chester and Catherine’s suite at the Fairfax Hotel in Washington, D. On March 9, 1945. [27] She had met Lay in the summer of 1934 while visiting her parents in Southeast Asia. Graduated from the U. Naval Academy in 1936 and served as a submariner in the Navy until his retirement in 1957, reaching the (post retirement) rank of rear admiral; he served as chairman of PerkinElmer from 19691980. Anna Elizabeth (“Nancy”) Nimitz was an expert on the Soviet economy at the RAND Corporation from 1952 until her retirement in the 1980s. Sister Mary Aquinas (Nimitz) became a sister in the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), working at the Dominican University of California. She taught biology for 16 years, and was academic dean for 11 years, acting president for one year, and vice president for institutional research for 13 years before becoming the university’s emergency preparedness coordinator. She held this job until her death, due to cancer, on February 27, 2006. In late 1965, Nimitz suffered a stroke, complicated by pneumonia. In January 1966, he left the U. Naval Hospital (Oak Knoll) in Oakland to return home to his naval quarters. He died at home at age 80 on the evening of February 20 at Quarters One on Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco Bay. [28] His funeral on February 24 was at the chapel of adjacent Naval Station Treasure Island and Nimitz was buried with full military honors at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno. [29][30][31][32][33] He lies alongside his wife and his long-term friends Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Admiral Richmond K. Turner, and Admiral Charles A. Lockwood and their wives, an arrangement made by all of them while living. Dates of rank[edit]. Jpg United States Naval Academy Midshipman January 1905. US Navy O1 insignia. US Navy O2 insignia. US Navy O3 insignia. US Navy O4 insignia. US Navy O5 insignia. US Navy O6 insignia. US Navy O7 insignia. US Navy O8 insignia. US Navy O9 insignia. US Navy O10 insignia. US Navy O11 insignia. Commodore no longer a rank in the United States Navy, was previously reserved for wartime use and was not in use at the time of Nimitz’s promotion to flag rank. Currently, a captain who is promoted to pay grade O-7 becomes a rear admiral (lower half) and uses the abbreviated rank designation RDML as opposed to RADM, which designates a rear admiral (upper half), O-8. During Admiral Nimitz’s service, the only rank existing among these was rear admiral, without distinction between upper and lower half. Fleet admiral rank made permanent in the United States Navy on May 13, 1946, a lifetime appointment. At the time of Nimitz’s promotion to rear admiral, the United States Navy did not maintain a one-star rank (Commodore). Nimitz was thus promoted directly from a captain to rear admiral. By Congressional appointment, he skipped the rank of vice admiral and became an admiral in December 1941. Nimitz also never held the rank of lieutenant junior grade, as he was appointed a full lieutenant after three years of service as an ensign. For administrative reasons, Nimitz’s naval record states that he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant junior grade and lieutenant on the same day. Decorations and awards[edit]. United States awards[edit]. Gold starGold starGold star. Navy Distinguished Service Medal with three gold stars. Army Distinguished Service Medal ribbon. Army Distinguished Service Medal. Silver Lifesaving Medal ribbon. World War I Victory Medal with Secretary of the Navy Commendation Star. American Defense Service Medal ribbon. American Defense Service Medal. Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal ribbon. World War II Victory Medal ribbon. World War II Victory Medal. National Defense Service Medal with service star. Order of the Bath UK ribbon. United Kingdom Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. Legion Honneur GO ribbon. France Grand-Officier de la Légion d’honneur. NLD Order of Orange-Nassau – Knight Grand Cross BAR. Netherlands Order of Orange-Nassau with Swords in the Degree of the Knight Grand Cross (Dutch: Ridder Grootkruis in de Orde van Oranje Nassau). GRE Order of George I – Grand Cross BAR. Greece Grand Cross of the Order of George I. Order of Precious Tripod with Special Grand Cordon ribbon. China Grand Cordon of Pao Ting (Tripod) Special Class. Guatemalan Armed Forces Cross. Guatemala Cross of Military Merit First Class (Spanish: La Cruz de Merito Militar de Primera Clase). Order of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes – Grand Cross (Cuba) – ribbon bar v. Cuba Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos Manuel de Cespedes. ARG Order of the Liberator San Martin – Knight BAR. Argentina Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Spanish: Orden del Libertador San Martin). Order of Abdón Calderón 1st Class (Ecuador) – ribbon bar. Ecuador Order of Abdon Calderon (1st Class). BEL Kroonorde Grootkruis BAR. Belgium Grand Cross Order of the Crown (Belgium) with Palm (French: Grand Croix de l’ordre de la Couronne avec palme). Cavaliere di gran Croce BAR. Italy Knight of the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy (Cavaliere di Gran Croce). Order of Naval Merit – Knight (Brazil) – ribbon bar. Brazil Order of Naval Merit (Ordem do Mérito Naval). Philippine Medal of Valor ribbon. Philippines Philippine Medal of Valor. Belgium War Cross with Palm (French: Croix de Guerre Avec Palme). United Kingdom Pacific Star. Philippines Liberation Medal with one bronze service star. Memorials and legacy[edit]. USS Nimitz at sea near Victoria, British Columbia. Nimitz’s headstone at Golden Gate National Cemetery. USS Nimitz, the first of her class of ten nuclear-powered supercarriers, which was commissioned in 1975 and remains in service. Nimitz Foundation, established in 1970, which funds the National Museum of the Pacific War and the Admiral Nimitz Museum, Fredericksburg, Texas. The Nimitz Freeway (Interstate 880) from Oakland to San Jose, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area. Nimitz Glacier in Antarctica for his service during Operation Highjump as the CNO. Nimitz Boulevard a major thoroughfare in the Point Loma Neighborhood of San Diego. Camp Nimitz, a recruit camp constructed in 1955 at the Naval Training Center, San Diego. The Nimitz Library, the main library at the U. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland. Nimitz Drive, in the Admiral Heights neighborhood of Annapolis, Maryland. Callaghan Hall (the Naval and Air Force ROTC building at UC Berkeley) containing the Nimitz Library (was gutted by arson in 1985). The town of Nimitz in Summers County, West Virginia. The summit on Guam where Chester Nimitz relocated his Pacific Fleet headquarters, and where the current Commander U. Naval Forces Marianas (ComNavMar) resides, is called Nimitz Hill. Nimitz Park, a recreational area located at United States Fleet Activities Sasebo, Japan. The Nimitz Trail in Tilden Park in Berkeley, California. The Main Gate at Pearl Harbor is called Nimitz Gate. Admiral Nimitz Circle located in Fair Park, Dallas, Texas. Chester Nimitz Oriental Garden Waltz performed by Austin Lounge Lizards. Admiral Nimitz Fanfare composed by John Steven Lasher (2014). Admiral Nimitz March composed by John Steven Lasher (2014). The Nimitz Building, Raytheon Company site headquarters, Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Nimitz Road in Diego Garcia, British Indian Ocean Territory is named in his honor. Nimitz Place part of Havemeyer Park located in Old Greenwich, Connecticut was named in his honor along with many other World War II military personnel. Nimitz Hall is the Officer Candidate School barracks of Naval Station Newport, Newport, Rhode Island. The barracks was dedicated March 15, 2013. Nimitz-McArthur Building, Headquarters U. Nimitz Statue, designed by Armando Hinojosa of Laredo, is located at the entrance to SeaWorld in San Antonio, Texas. Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Statue, commissioned by the Naval Order of the United States, is situated near the bow of the USS Missouri memorial on Ford Island, facing the USS Arizona memorial. The statue was dedicated September 2, 2013. Nimitz Beach Park, Agat, Guam. Nimitz High School, (Harris County, Texas). Nimitz High School, Irving, Texas. Nimitz Junior High School, Odessa, Texas. Nimitz Middle School, Huntington Park, California. Nimitz Middle School, San Antonio, Texas. Nimitz Elementary School, Sunnyvale, California. Nimitz Elementary School, Kerrville, Texas. United States Navy portal. World War I portal. World War II portal. Henry Arnold Karosee hand-written inscription on photo given to Adm. Admiral of the Navy. Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey Jr. KBE (October 30, 1882 August 16, 1959), [2] known as Bill Halsey or “Bull” Halsey, was an American admiral in the United States Navy during World War II. He is one of the four individuals to have attained the rank of fleet admiral of the United States Navy. Born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Halsey graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1904. He served in the Great White Fleet and, during World War I, commanded the USS Shaw. He took command of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga in 1935 after completing a course in naval aviation, and was promoted to the rank of rear admiral in 1938. At the start of the War in the Pacific (194145) Halsey commanded the task force centered on the carrier USS Enterprise in a series of raids against Japanese-held targets. Halsey was made commander, South Pacific Area and led the Allied forces over the course of the Battle for Guadalcanal (194243) and the fighting up the Solomon chain (194245). [3] In 1943 he was made commander of the Third Fleet, the post he held through the rest of the war. [4] He took part in the Battle for Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the Second World War and, by some criteria, the largest naval battle in history. He was promoted to fleet admiral in December 1945 and retired from active service in March 1947. Halsey was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on October 30, 1882, the son of U. Navy Captain William F. Through his father he was a descendant of Senator Rufus King, who was an American lawyer, politician, diplomat, and Federalist. Halsey attended the Pingry School. After waiting two years to receive an appointment to the United States Naval Academy, Halsey decided to study medicine at the University of Virginia and then join the Navy as a physician. He chose Virginia because his best friend, Karl Osterhause, was there. While there, Halsey joined the Delta Psi fraternity and was also a member of the secretive Seven Society. [6] After his first year, Halsey received his appointment to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, and entered the Academy in the fall of 1900. While attending the academy he lettered in football as a fullback and earned several athletic honors. Halsey graduated from the Naval Academy on February 2, 1904. Following graduation he spent his early service years in battleships, and sailed with the main battle fleet aboard the battleship USS Kansas (BB-21) as Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet circumnavigated the globe from 1907 to 1909. Halsey was on the bridge of the battleship USS Missouri on Wednesday, April 13, 1904, when a flareback from the port gun in her after turret ignited a powder charge and set off two others. No explosion occurred, but the rapid burning of the powder burnt and suffocated to death 31 officers and men. This resulted in Halsey dreading the 13th of every month, especially when it fell on a Friday. After his service on the Missouri, Halsey served aboard torpedo boats, beginning with USS Du Pont in 1909. Halsey was one of the few officers who was promoted directly from Ensign to full lieutenant, skipping the rank of lieutenant (junior grade). [9] Torpedoes and torpedo boats became specialties of his, and he commanded the First Group of the Atlantic Fleet’s Torpedo Flotilla in 1912 through 1913. Halsey commanded a number of torpedo boats and destroyers during the 1910s and 1920s. Lieutenant Commander Halsey’s World War I service, including command of USS Shaw in 1918, earned him the Navy Cross. In October 1922, he was the naval attaché at the American Embassy in Berlin, Germany. One year later, he was given additional duty as naval attaché at the American Embassies in Christiania, Norway; Copenhagen, Denmark; and Stockholm, Sweden. Upon his return to the U. Captain Halsey continued his destroyer duty on his next two-year stint at sea, starting in 1930 as Commander Destroyer Division Three of the Scouting Force, before returning to study at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1934 the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, Navy Admiral Ernest King, offered Halsey command of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga, subject to completion of the course of an air observer. Captain Halsey elected to enroll as a cadet for the full 12-week Naval Aviator course rather than the simpler Naval Aviation Observer program. I thought it better to be able to fly the aircraft itself than to just sit back and be at the mercy of the pilot. Halsey earned his Naval Aviator’s Wings on May 15, 1935, at the age of 52, the oldest person to do so in the history of the U. While he had approval from his wife to train as an observer, she learned from a letter after the fact that he had changed to pilot training, and she told her daughter, What do you think that the old fool is doing now? He’s learning to fly! [11] He went on to command the Saratoga, and later the Naval Air Station Pensacola at Pensacola, Florida. Halsey considered airpower an important part of the future navy, commenting, The naval officer in the next war had better know his aviation, and good. Captain Halsey was promoted to rear admiral in 1938. During this time he commanded carrier divisions and served as the overall commander of the Aircraft Battle Force. Traditional naval doctrine envisioned naval combat fought between opposing battleship gun lines. This view was challenged when army airman General Billy Mitchell demonstrated the capability of aircraft to substantially damage and sink even the most heavily armored naval vessel. In the interwar debate that followed, some saw the carrier as defensive in nature, providing air cover to protect the battle group from shore-based aircraft. Carrier-based aircraft were lighter in design and had not been shown to be as lethal. The adage “Capital ships cannot withstand land-based air power” was well known. [12] Aviation proponents, however, imagined bringing the fight to the enemy with the use of air power. [13] Halsey was a firm believer in the aircraft carrier as the primary naval offensive weapon system. When he testified at Admiral Husband Kimmel’s hearing after the Pearl Harbor debacle he summed up American carrier tactics being to get to the other fellow with everything you have as fast as you can and to dump it on him. Halsey testified he would never hesitate to use the carrier as an offensive weapon. With tensions high and war imminent, U. Naval intelligence indicated Wake Island would be the target of a Japanese surprise attack. In response, on 28 November 1941 Admiral Kimmel ordered Halsey to take USS Enterprise to ferry aircraft to Wake Island to reinforce the Marines there. Kimmel had given Halsey “a free hand” to attack and destroy any Japanese military forces encountered. [9] The planes flew off her deck on December 2. ” Protested his operations officer, “Goddammit, Admiral, you can’t start a private war of your own! Who’s going to take the responsibility? ” Said Halsey: “I’ll take it! If anything gets in my way, we’ll shoot first and argue afterwards. Instead of returning on December 6 as planned, she was still 200 miles out at sea, when she received word that the surprise attack anticipated was not at Wake Island, but at Pearl Harbor itself. News of the attack came in the form of overhearing desperate radio transmissions from one of her aircraft sent forward to Pearl Harbor, attempting to identify itself as American. [15] The plane was shot down, and her pilot and crew were lost. In the immediate wake of the attack upon Pearl Harbor, Admiral Kimmel named Halsey commander of all the ships at sea. [9] Enterprise searched south and west of the Hawaiian islands for the Japanese attackers, but did not locate the six Japanese fleet carriers then retiring to the north and west. Early Pacific carrier raids[edit]. An SBD Dauntless flies anti-submarine patrol over Enterprise and Saratoga. Vice Admiral Halsey and Enterprise slipped back into Pearl Harbor on the evening of December 8. Surveying the wreckage of the Pacific Fleet, he remarked, Before we’re through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell. [16] Halsey was an aggressive commander. Above all else, he was an energetic and demanding leader who had the ability to invigorate the U. Navy’s fighting spirit when most required. [17] In the early months of the war, as the nation was rocked by the fall of one western bastion after another, Halsey looked to take the fight to the enemy. Serving as commander, Carrier Division 2 aboard his flagship Enterprise, Halsey led a series of hit-and-run raids against the Japanese, striking the Gilbert and Marshall islands in February, Wake Island in March, and carrying out the Doolittle Raid in April, 1942 against the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Japan’s largest and most populous island Honshu, the first air raid to strike the Japanese Home Islands, providing an important boost to American morale. Halsey’s slogan, “Hit hard, hit fast, hit often” soon became a byword for the Navy. He had spent nearly all of the previous six months on the bridge of the carrier Enterprise, directing the Navy’s counterstrikes. A debilitating chronic skin condition covered a great deal of his body and caused unbearable itching, making it nearly impossible for him to sleep. Naval intelligence had strongly ascertained that the Japanese were planning an attack on the Central Pacific island of Midway. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U. Pacific Fleet, determined to take the opportunity to engage them. The loss of his most aggressive and combat experienced carrier admiral, Halsey, on the eve of this crisis was a severe blow to Nimitz. [18] Nimitz met with Halsey, who recommended his cruiser division commander, Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance, to take command for the upcoming Midway operation. [19] Nimitz considered the move, but it would mean stepping over Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher of Task Force 17, who was the senior of the two men. After interviewing Fletcher and reviewing his reports from the Coral Sea engagement, Nimitz was convinced that Fletcher’s performance was sound, and he was given the responsibility of command in the defense of Midway. [20] Acting upon Halsey’s recommendations, Nimitz then made Rear Admiral Spruance commander of Halsey’s Task Force 16, comprising the carriers Enterprise and Hornet. To aid Spruance, who had no experience as the commander of a carrier force, Halsey sent along his irascible chief of staff, Captain Miles Browning. The ensuing harrowing Battle of Midway was a crucial turning point in the war for the United States and a dramatic victory for the U. Halsey’s skin condition was so serious, he was sent on the light cruiser USS Detroit to San Francisco where he was met by a leading allergist for specialized treatment. The skin condition soon receded but Halsey was ordered to stand down for the next 6 weeks and relax. While detached stateside during his convalescence, he visited family and travelled to Washington D. In late August, he accepted a speaking engagement at the U. Naval Academy at Annapolis. At the completion of his convalescence in September 1942 Admiral Nimitz reassigned Halsey to Commander, Air Force, Pacific Fleet. South Pacific Area Command[edit]. Halsey in the South Pacific. After being medically approved to return to duty, Halsey was named to command a carrier task force in the South Pacific Area. Since Enterprise was still laid up in Pearl Harbor undergoing repairs following the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, and the other ships of Task Force 16 were still being readied, he began a familiarization trip to the south Pacific on October 15, 1942, arriving at area headquarters at Nouméa in New Caledonia on the 18th. The Guadalcanal Campaign was at a critical juncture, with the 1st Marine Division, 11,000 men, under the combat command of Marine Major General Alexander A. Vandergrift holding on by a thread around Henderson (Air) Field. The Marines did receive additional support from the U. Army’s 164th Regiment with a complement of 2,800 soldiers on October 13. This addition only helped to fill some of the serious holes and was insufficient to sustain the battle of itself. During this critical juncture, naval support was tenuous due to Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley’s reticence, malaise and lackluster performance. [9] Pacific Fleet commander Chester Nimitz had concluded that Vice Admiral Ghormley had become dispirited and exhausted. [22] Nimitz made his decision to change the South Pacific Area command while Halsey was en route. As Halsey’s aircraft came to rest in Nouméa, a whaleboat came alongside carrying Ghormley’s flag lieutenant. Meeting him before he could board the flagship, the lieutenant handed over a sealed envelope containing a message from Nimitz. YOU WILL TAKE COMMAND OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC AREA AND SOUTH PACIFIC FORCES IMMEDIATELY[3]. The order came as an awkward surprise to Halsey. Ghormley was a long time personal friend, and had been since their days as teammates on the football team back at Annapolis. Awkward or not, the two men carried out their directives. Halsey’s command now included all ground, sea, and air forces in the South Pacific area. News of the change flashed and produced an immediate boost to morale with the beleaguered Marines, energizing his command. He was widely considered the U. Navy’s most aggressive admiral, and with good reason. He set about assessing the situation to determine what actions were needed. Ghormley had been unsure of his command’s ability to maintain the Marine toehold on Guadalcanal, and had been mindful of leaving them trapped there for a repeat of the Bataan Peninsula disaster. Halsey punctiliously made it clear he did not plan to withdraw the Marines. He not only intended to counter the Japanese efforts to dislodge them, he intended to secure the island. Above all else, he wanted to regain the initiative and take the fight to the Japanese. It was two days after Halsey had taken command in October 1942 that he gave an order that all naval officers in the South Pacific would dispense with wearing neckties with their tropical uniforms. As Richard Frank commented in his account of the Battle for Guadalcanal. Halsey said he gave this order to conform to Army practice and for comfort. To his command it viscerally evoked the image of a brawler stripping for action and symbolized a casting off of effete elegance no more appropriate to the tropics than to war. Halsey led the South Pacific command through what was for the U. Navy the most tenuous phase of the war. Halsey committed his limited naval forces through a series of naval battles around Guadalcanal, including the carrier engagements of the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. These engagements checked the Japanese advance and drained their naval forces of carrier aircraft and pilots. Admirals Nimitz and Halsey discuss South Pacific strategy in early 1943. In November Halsey’s willingness to place at risk his command’s two fast battleships in the confined waters around Guadalcanal for a night engagement paid off with the U. Navy winning the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the decisive naval engagement of the Guadalcanal campaign that doomed the Japanese garrison and wrested control from the Japanese. IJN aviation proved to be formidable during the Solomon campaign. [24] In April 1943, Halsey assigned Admiral Marc Mitscher to Commander Air, Solomon Islands (ComAirSols) where he directed a mixed bag of Army, Navy, Marine and New Zealand aircraft in the airwar over Guadalcanal and up the Solomon chain. Said Halsey: I knew we’d probably catch hell from the Japs in the air. That’s why I sent Pete Mitscher up there. Pete was a fighting fool and I knew it. South Pacific Command was expecting the arrival of an additional air group to support their next offensive. As a part of the long view of winning the war taken by Nimitz, upon its arrival at Fiji the group was given new orders to return stateside and be broken up, its pilots to be used as instructors for pilot training. South Pacific command had been counting on the air group for their operations up the Solomon chain. The staff officer who brought the dispatch to Halsey remarked If they do that to us we will have to go on the defensive. ” The admiral turned to the speaker and replied: “As long as I have one plane and one pilot, I will stay on the offensive. Admiral Halsey’s forces spent the rest of the year battling up the Solomon Islands chain to Bougainville. At Bougainville the Japanese had two airfields in the southern tip of the island, and another at the northern most peninsula, with a fourth on Buki just across the northern passage. Here, instead of landing near the Japanese airfields and taking them away against the bulk of the Japanese defenders, Halsey landed his invasion force of 14,000 marines in Empress Augusta Bay, about halfway up the west coast of Bougainville. There he had the Seabees clear and build their own airfield. Two days after the landing, a large cruiser force was sent down from Japan to Rabaul in preparation for a night engagement against Halsey’s screening force and supply ships in Empress Augusta Bay. The Japanese had been conserving their naval forces over the past year, but now committed a force of seven heavy cruisers, along with one light cruiser and four destroyers. At Rabaul the force refueled in preparation for the coming night battle. Halsey had no surface forces anywhere near equivalent strength to oppose them. The battleships Washington, South Dakota and assorted cruisers had been transferred to the Central Pacific to support the upcoming invasion of Tarawa. Other than the destroyer screen, the only force Halsey had available were the carrier airgroups on Saratoga and Princeton. Rabaul was a heavily fortified port, with five airfields and extensive anti-aircraft batteries. Other than the surprise raid at Pearl Harbor, no mission against such a target had ever been accomplished with carrier aircraft. It was highly dangerous to the aircrews, and to the carriers as well. With the landing in the balance, Halsey sent his two carriers to steam north through the night to get into range of Rabaul, then launch a daybreak raid on the base. Aircraft from recently captured Vella Lavella were sent over to provide a combat air patrol over the carriers. All available aircraft from the two carriers were committed to the raid itself. The mission was a stunning success, so damaging the cruiser force at Rabaul as to make them no longer a threat. Aircraft losses in the raid were light. Halsey later described the threat to the landings the most desperate emergency that confronted me in my entire term as ComSoPac. Following the successful Bougainville operation, he then isolated and neutralized the Japanese naval stronghold at Rabaul by capturing surrounding positions in the Bismarck Archipelago in a series of amphibious landings known as Operation Cartwheel. This enabled the continuation of the drive north without the heavy fighting that would have been necessary to capture the base itself. With the neutralization of Rabaul, major operations in the South Pacific Command came to a close. With his determination and grit, Halsey had bolstered his command’s resolve and seized the initiative from the Japanese until ships, aircraft and crews produced and trained in the States could arrive in 1943 and 1944 to tip the scales of the war in favor of the allies. Battles of the Central Pacific[edit]. Halsey (right) confers with Task Force 38 commander and fellow’dirty trickster’ Adm. On board Halsey’s flagship, the USS New Jersey, 1944. As the war progressed it moved out of the South Pacific and into the Central Pacific. Admiral Halsey’s command shifted with it, and in May 1944 he was promoted to commanding officer of the newly formed Third Fleet. He commanded actions from the Philippines to Japan. From September 1944 to January 1945, he led the campaigns to take the Palaus, Leyte and Luzon, and on many raids on Japanese bases, including off the shores of Formosa, China, and Vietnam. By this point in the conflict the U. Navy was doing things the Japanese high command had not thought possible. The Fast Carrier Task Force was able to bring to battle enough air power to overpower land based aircraft and dominate whatever area the fleet was operating in. Moreover, the Navy’s ability to establish forward operating ports as they did at Majuro, Enewetak and Ulithi, and their ability to convoy supplies out to the combat task forces allowed the fleet to operate for extended periods of time far out to sea in the central and western Pacific. The Japanese Navy conserved itself in port and would sortie in force to engage the enemy. Navy remained at sea and on station, dominating whatever region it entered. The size of the Pacific Ocean, which Japanese planners had thought would limit the U. Navy’s ability to operate in the western Pacific, would not be adequate to protect Japan. Command of the “big blue fleet” was alternated with Raymond Spruance. [N 1] Under Spruance the fleet designation was the Fifth Fleet and the Fast Carrier Task Force was designated “Task Force 58″. Under Halsey the fleet was designated Third Fleet and the Fast Carrier Task Force was designated “Task Force 38″. [4] The split command structure was intended to confuse the Japanese and created a higher tempo of operations. While Spruance was at sea operating the fleet, Halsey and his staff, self-dubbed the “Department of Dirty Tricks”, would be planning the next series of operations. [29] The two admirals were a contrast in styles. Halsey was aggressive and a risk taker. Spruance was calculating, professional and cautious. Most higher-ranking officers preferred to serve under Spruance; most common sailors were proud to serve under Halsey. Halsey dines with crew of USS New Jersey (November 1944). In October 1944, amphibious forces of the U. Seventh Fleet carried out General Douglas MacArthur’s major landings on the island of Leyte in the Central Philippines. Halsey’s Third Fleet was assigned to cover and support Seventh Fleet operations around Leyte. Halsey’s plans assumed the Japanese fleet or a major portion of it would challenge the effort, creating an opportunity to engage it decisively. Halsey directed the Third Fleet will seek the enemy and attempt to bring about a decisive engagement if he undertakes operations beyond support of superior land based air forces. In response to the invasion, the Japanese launched their final major naval effort, an operation known as’Sho-Go’, involving almost all their surviving fleet. The Northern Force of Admiral Ozawa was built around the remaining Japanese aircraft carriers, now weakened by the heavy loss of trained pilots. The Northern Force was meant to lure the covering U. These forces were built around the remaining strength of the Japanese Navy, and comprised a total of 7 battleships and 16 cruisers. The operation brought about the Battle for Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the Second World War and, by some criteria, the largest naval battle in history. The Center Force commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita was located October 23 coming through the Palawan Passage by two American submarines, which attacked the force, sinking two heavy cruisers and damaging a third. The following day Third Fleet’s aircraft carriers launched strikes against Kurita’s Center Force, sinking the battleship Musashi and damaging the heavy cruiser Myk, causing the force to turn westward back towards its base. Kurita appeared to be retiring but he later reversed course and headed back into the San Bernardino Strait. At this point Ozawa’s Northern Force was located by Third Fleet scout aircraft. Halsey made the momentous decision to take all available strength northwards to destroy the Japanese carrier forces, planning to strike them at dawn of October 25. He considered leaving a battle group behind to guard the strait, and made tentative plans to do so, but he felt he would also have to leave one of his three carrier groups to provide air cover, weakening his chance to crush the remaining Japanese carrier forces. The entire Third Fleet steamed northward. San Bernardino Strait was effectively left unguarded by any major surface fleet. Battle off Samar[edit]. In moving Third Fleet northwards, Halsey failed to advise Admiral Thomas Kinkaid of Seventh Fleet of his decision. Seventh Fleet intercepts of organizational messages from Halsey to his own task group commanders seemed to indicate that Halsey had formed a task force and detached it to protect the San Bernardino Strait, but this was not the case. Kinkaid and his staff failed to confirm this with Halsey, and neither had confirmed this with Nimitz. Despite aerial reconnaissance reports on the night of 2425 October of Kurita’s Center Force in the San Bernardino Strait, Halsey continued to take Third Fleet northwards, away from Leyte Gulf. Halsey with Vice Admiral John S. When Kurita’s Center Force emerged from the San Bernardino Strait on the morning of October 25, there was nothing to oppose them except a small force of escort carriers and screening destroyers and destroyer escorts, Task Unit 77.4.3 “Taffy 3″, which had been tasked and armed to attack troops on land and guard against submarines[clarification needed], not oppose the largest enemy surface fleet since Midway led by the largest battleship in the world. Advancing down the coast of the island of Samar towards the troop transports and support ships of the Leyte Gulf landing, they took Seventh Fleet’s escort carriers and their screening ships entirely by surprise. In the desperate Battle off Samar which followed, Kurita’s ships destroyed one of the escort carriers and three ships of the carriers’ screen, and damaging a number of other ships as well. The remarkable resistance of the screening ships of the escort carrier groups against Kurita’s battle-group remains one of the most heroic feats in the storied history of the US Navy. Their efforts and those of the aircraft that the escort carriers could put up took a heavy toll on Kurita’s ships and convinced him that he was facing a stronger force than was the case. Mistaking the escort carriers for Halsey’s fleet carriers, and fearing entrapment from the six battleships of the Third Fleet battleship group, he decided to withdraw back through the San Bernardino Strait and to the west without achieving his objective of the Leyte landing. When the Seventh Fleet’s escort carriers found themselves under attack from the Center Force, Halsey began to receive a succession of desperate calls from Kinkaid asking for immediate assistance off Samar. For over two hours Halsey turned a deaf ear to these calls. Then, shortly after 10:00 hours, [32] a message was received from Admiral Nimitz: Where is repeat where is Task Force 34? The tail end of this message, The world wonders, was intended as padding designed to confuse enemy decoders, but was mistakenly left in the message when it was handed to Halsey. The urgent inquiry had seemingly become a stinging rebuke. The fiery Halsey threw his hat on the deck of the bridge and began cursing. [32] Finally Halsey’s Chief of Staff, Rear Admiral Robert “Mick” Carney, confronted him, telling Halsey Stop it! What the hell’s the matter with you? Halsey cooled but continued to steam Third Fleet northward to close on Ozawa’s Northern Force for a full hour after receiving the signal from Nimitz. [32] Then, Halsey ordered Task Force 34 south. As Task Force 34 proceeded south they were further delayed when the battle force had to slow to 12 knots so that the battleships could refuel their escorting destroyers. The refueling cost a two and a half hour further delay. [32] By the time Task Force 34 arrived at the scene it was too late to assist the Seventh Fleet’s escort carrier groups. Kurita had already decided to retire and had left the area. A single straggling destroyer was caught by Halsey’s advance cruisers and destroyers, but the rest of Kurita’s force was able to escape. Meanwhile the major part Third Fleet continued to close on Ozawa’s Northern Force, which included one fleet carrier (the last surviving Japanese carrier of the six that had attacked Pearl Harbor) and three light carriers. The Battle of Cape Engaño resulted in Halsey’s Third Fleet sinking all four of Ozawa’s carriers. The same attributes that made Halsey an invaluable leader in the desperate early months of the war, his desire to bring the fight to the enemy, his willingness to take on a gamble, worked against him in the later stages of the war. Halsey received much criticism for his decisions during the battle, with naval historian Samuel Morison terming the Third Fleet run to the north Halsey’s Blunder. [33] However, the destruction of the Japanese carriers had been the prime goal of Pacific naval battles up to that point, and the failure to pursue the Japanese fleet carriers and destroy them had been a major criticism of Spruance in some circles, whose Fifth Fleet missed the opportunity at the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Halsey’s Typhoon[edit]. Main article: Typhoon Cobra (1944). USS Langley struggles in Typhoon Cobra. After the Leyte Gulf engagement, December found the Third Fleet confronted with another powerful enemy in the form of Typhoon Cobra which was dubbed “Halsey’s Typhoon” by many. While conducting operations off the Philippines, the fleet had to discontinue refueling due to a Pacific storm. Rather than move Third Fleet away, Halsey chose to remain on station for another day. In fairness, he received conflicting information from Pearl Harbor and his own staff. The Hawaiian weathermen predicted a northerly path for the storm, which would have cleared Task Force 38 by some two hundred miles. Eventually his own staff provided a prediction regarding the direction of the storm that was far closer to the mark with a westerly direction. [34] However, Halsey played the odds, declining to cancel planned operations and requiring the ships of Third Fleet to hold formation. On the evening of December 17 the combat air patrol over Third Fleet was unable to land their aircraft aboard the pitching and rolling carriers. The pilots were forced to ditch in the ocean. The aircraft were lost but all the pilots were picked up by escorting destroyers. Still the fleet attempted to maintain stations. Finally, at 11:49 a. Halsey issued the order for the ships of the fleet to take the most comfortable course available to them, something which many ships had already been forced to do. Between 11:00 a. And 2:00 p. The typhoon did its worst damage, tossing the ships in seventy-foot waves. The barometer continued to drop and the wind roared at eighty-three knots with gusts well over 100 knots. At 1:45 p. Halsey issued a typhoon warning to Fleet Weather Central. By this time the Third Fleet had already lost three destroyers. The storm inflicted damage on a great many ships in the fleet, with the loss of some 802 men and 146 aircraft. Third Fleet conducted search and rescue operations for three days following the storm, finally retiring for repairs at Ulithi on December 22. Following the typhoon a Navy court of inquiry was convened on board the USS Cascade (AD-16) in the Naval base at Ulithi. Admiral Nimitz, CINCPAC, was in attendance at the court. Forty-three-year-old Captain Herbert K. Gates, of the Cascade, was the Judge Advocate. [35] The inquiry found that though Halsey had committed an error of judgement in sailing the Third Fleet into the heart of the typhoon, it stopped short of unambiguously recommending sanction. [36] The events surrounding Typhoon Cobra were similar to those the Japanese navy itself faced some nine years earlier in what they termed The Fourth Fleet Incident. End of the war[edit]. Fleet Admiral Nimitz signing the documents of surrender on board USS Missouri. Behind him stand Gen. William Halsey and Rear Adm. During January 1945 the Third Fleet attacked Formosa and Luzon, and raided the South China Sea in support of the landing of US Army forces on Luzon. At the conclusion of this operation, Halsey passed command of the ships that made up Third Fleet to Admiral Spruance on 26 January, whereupon its designation changed to Fifth Fleet. Returning home Halsey was asked about General MacArthur. General MacArthur was not the easiest man to work with, and vied with the Navy over the conduct and management of the war in the Pacific. [38] Halsey had worked well with MacArthur and did not mind saying so. When a reporter asked Halsey if he thought General MacArthur’s fleet (7th Fleet) would get to Tokyo first, the admiral grinned and answered We’re going there together. ” Then seriously he added “He’s a very fine man. I have worked under him for over two years and have the greatest admiration and respect for him. In early June 1945 3rd Fleet again sailed through the path of Typhoon Connie. On this occasion, six men were swept overboard and lost, along with 75 airplanes lost or destroyed, with another 70 badly damaged. Though some ships sustained significant damage, none were lost. A Navy court of inquiry was again convened, this time recommending that Halsey be reassigned, but Admiral Nimitz declined to abide by this recommendation, citing Halsey’s prior service record, despite that record including a previous instance of negligently sailing his fleet through a typhoon. Halsey led Third Fleet through the final stages of the war, striking targets on the Japanese homeland itself. Third Fleet aircraft conducted attacks upon Tokyo, the naval base at Kure and the northern Japanese island of Hokkaid, and Third Fleet battleships engaged in the bombardment of a number of Japanese coastal cities in preparation for an invasion of Japan, which ultimately never had to be undertaken. After the cessation of hostilities, Halsey, still aggressively cautious of Japanese kamikaze attacks, ordered Third Fleet to maintain a protective air cover with the following communiqué. If any Japanese airplanes appear, shoot them down in a friendly way. He was present when Japan formally surrendered on the deck of his flagship, USS Missouri, on September 2, 1945. He hauled down his flag in November of that year and was assigned special duty in the office of the Secretary of the Navy. On December 11, 1945, he took the oath as Fleet Admiral, becoming the fourth and still the most recent naval officer awarded that rank. Fleet Admiral Halsey made a goodwill flying trip, passing by Central and South America, covering nearly 28,000 miles and 11 nations. He retired from active service in March 1947 but, as a Fleet Admiral, he was not taken off active duty status. Halsey was asked about the weapons used to win the war and he answered. If I had to give credit to the instruments and machines that won us the war in the Pacific, I would rate them in this order: submarines first, radar second, planes third, bulldozers fourth. Halsey joined the New Jersey Society of the Sons of the American Revolution in 1946. Upon retirement, he joined the board of two subsidiaries of the International Telephone and Telegraph Company, including the American Cable and Radio Corporation, and served until 1957. He maintained an office near the top of the ITT Building at 67 Broad Street, New York City in the late 1950s. He was involved in a number of efforts to preserve his former flagship USS Enterprise (CV-6) as a memorial in New York harbor. Halsey died on August 16, 1959, while holidaying on Fishers Island, New York. [42] After lying in state in the Washington National Cathedral, he was interred on August 20, 1959, near his parents in Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Frances Grandy Halsey, is buried with him. Asked about his contribution in the Pacific and the role he played in defending the United States, Halsey said merely. There are no great men, just great challenges which ordinary men, out of necessity, are forced by circumstances to meet. While at the University of Virginia he met Frances Cooke Grandy (18871968) of Norfolk, Virginia, who Halsey called Fan. After his return from the Great White Fleet’s circumnavigation of the globe and upon his promotion to the rank of full lieutenant he was able to persuade her to marry him. [44] They married on December 1, 1909, at Christ Church in Norfolk. Among the ushers were Halsey’s friends Thomas C. Hart and Husband E. Fan developed manic depression in the late 1930s and eventually had to live apart from Halsey. [45] The couple had two children, Margaret Bradford (October 10, 1910, to December 1979) and William Fredrick Halsey III (Sept 8, 1915, to Sept 23, 2003). Jpg United States Naval Academy MidshipmanClass of 1904. Halsey never held the rank of lieutenant (junior grade), as he was appointed a full lieutenant after three years of service as an ensign. For administrative reasons, Halsey’s naval record states he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) and lieutenant on the same day. At the time of Halsey’s promotion to rear admiral, both rear admirals lower half (O-7) and rear admirals upper half (O-8) wore two stars. This was the case until 1982. During World War II and up until 1950, the Navy used the one star commodore rank for certain staff specialties. Awards and decorations[edit]. Presidential Unit Citation (United States) with service star. Mexican Service Medal ribbon. World War I Victory Medal with Destroyer clasp. American Defense Service Medal with Fleet clasp. Silver starSilver starBronze starBronze star. Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with twelve battle stars. National Defense Service Medal ribbon. National Defense Service Medal. Argentina Order of Naval Merit, Grand Cross (March 1, 1947). Brazil Order of the Southern Cross, Grand Cross. Chile Grand Cross of Order of Merit of Chile. Colombia Grand Cross of Boyaca. Panama Orden Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Grand Cross. Order of the Quetzal – Grand Cross (Guatemala) – ribbon bar. Guatemala made him a Supreme Chief in the Order of the Quetzal. Ecuador Order of Abdon Calderón, 1st Class. United Kingdom Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE). Chile Al Merito, First Class, Insignia and Diploma. Cuba Order of Naval Merit (Cuba). GRE Order Redeemer 5Class. Greece Order of the Redeemer. Peru Order of Ayacucho. Venezuela Order of the Liberator. Philippines Philippine Presidential Unit Citation. Philippines Philippine Liberation Medal with two stars. [48][49][50][51]. Halsey Field, NAS North Island in Coronado, California, dedicated October 20, 1960 celebrating 50 years of Naval Aviation (19111961). Halsey Society, student Naval ROTC organization at Texas A&M University[53]. Leadership Academy & William F. Halsey House, Elizabeth High School in Elizabeth, New Jersey[54]. Halsey Field House, United States Naval Academy. Halsey Hall, University of Virginia. Halsey Hall, Jonathan Dayton High School. USS Halsey (BEQ-439), A Junior Enlisted Barracks for Students going through initial training in Naval Station Great Lakes, IL. USS Halsey (CG-23), a Leahy-class guided-missile cruiser. USS Halsey (DDG-97), an Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer. Halsey Street sign in Alexandria, Louisiana. Admiral Halsey Slope sign in Nouméa, New Caledonia. Admiral Halsey Drive, NE, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Halsey Street, Alexandria, Louisiana. Halsey Street, Auckland, New Zealand. Halsey Avenue, Bakersfield, California. Halsey Road Dover, Delaware. Halsey Place, Baltimore, Maryland. Halsey Street, Chula Vista, California. Admiral Halsey Avenue, Daytona Beach, Florida[56]. Halsey Drive, Flower Mound, Texas. Halsey Avenue, Middletown, Rhode Island. Halsey Street, Newport, Rhode Island. Halsey Drive, Warwick, Rhode Island. Halsey Street, Newark, New Jersey. Admiral Halsey Service Area, a north-bound rest area along the New Jersey Turnpike at mile marker 111 on Interstate 95, at the present New Jersey Route 81 interchange, in New Jersey[57]. Admiral Halsey Slope, Nouméa, New Caledonia. Halsey Court, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Admiral Halsey Road, Plymouth, Massachusetts. Halsey Court, Princeton, New Jersey. Halsey Street, Princeton, New Jersey. Halsey Street, Colonel Bud Day Field, Sioux City, Iowa. Halsey Avenue, Yuba City, California. Halsey Road, Toms River, New Jersey. Halsey Street, San Leandro, California. S Halsey Dr, Whidbey Island. Halsey Dr, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana. Halsey Drive, Riverside, Ohio. Halsey Rd, Jacksonville, FL. Halsey Street, East Hartford, Connecticut. In popular culture[edit]. Halsey was portrayed by James Cagney in the 1959 bio-pic, The Gallant Hours; by James Whitmore in the 1970 film, Tora! And by Robert Mitchum in the 1976 film, Midway. Halsey makes a brief appearance in Herman Wouk’s novel The Winds of War, and has a more substantial supporting role in the sequel War and Remembrance. (Chapter 92) Halsey was portrayed in the 1983 television miniseries adaptation of The Winds of War by Richard X. Slattery, and in the 1988 miniseries adaptation of War and Remembrance by Pat Hingle. Halsey has been portrayed in a number of other films and TV miniseries, played by Glenn Morshower (Pearl Harbor, 2001), Kenneth Tobey (MacArthur, 1977), Jack Diamond (Battle Stations, 1956), John Maxwell, (The Eternal Sea, 1955) and Morris Ankrum (Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, 1944). An “Admiral Halsey” is mentioned in the Paul and Linda McCartney song “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey”. The chorus of “hands across the water, heads across the sky” was a reference to the American aid programs of World War II. McCartney later specified that the second half of the song was indeed in honor of William Halsey. On March 4, 1951, Halsey appeared as a mystery guest on episode No. 40 of the game show, What’s My Line, where the panel correctly deduced his identity. In the television series, McHale’s Navy, one of Captain Binghampton’s catchphrases whenever he would get frustrated with one of McHale’s schemes was, What in the name of Halsey is going on here? Halsey is mentioned in the 1990 film The Hunt for Red October. Soviet submarine commander Marko Ramius, while engaged in battle with the Soviet attack submarine Konovalov, asks Jack Ryan what books he wrote for the CIA. Ryan mentions one about Admiral Halsey, entitled The Fighting Sailor (not to be confused with a real book of the same title); Ramius reveals his awareness of the book and expresses disdain for Ryan’s assessment of Halsey, saying, Your conclusions were all wrong, Ryan. The fictional aircraft carrier USS William Halsey in Darren Sapp’s novel, Fire on the Flight Deck, is named for Halsey. List of Fleet and Grand Admirals. List of United States military leaders by rank. List of military figures by nickname. The United States Navy grew rapidly during World War II from 194145, and played the central role in the war against Japan, and (after the British Royal Navy) a major role in the European war against Germany and Italy. Navy grew into a formidable force in the years prior to World War II, with battleship production being restarted in 1937, commencing with the USS North Carolina (BB-55). It was able to add to its fleets during the early years of the war while the US was still neutral, increasing production of vessels both large and small, deploying a navy of nearly 350 major combatant ships by December 1941 and having an equal number under construction. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) sought naval superiority in the Pacific by sinking the main American battle fleet at Pearl Harbor, which was built around its battleships. The December 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor did knock out the battle fleet, but it did not touch the aircraft carriers, which became the mainstay of the rebuilt fleet. Naval doctrine had to be changed overnight. The United States Navy (like the IJN) had followed Alfred Thayer Mahan’s emphasis on concentrated groups of battleships as the main offensive naval weapons. [2] The loss of the battleships at Pearl Harbor forced Admiral Ernest J. King, the head of the Navy, to place primary emphasis on the small number of aircraft carriers. Navy grew tremendously as the United States was faced with a two-front war on the seas. It achieved notable acclaim in the Pacific Theater, where it was instrumental to the Allies’ successful “island hopping” campaign. Navy fought six great battles with the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN): the Attack on Pearl Harbor, Battle of the Coral Sea, the Battle of Midway, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and the Battle of Okinawa. By war’s end in 1945, the United States Navy had added nearly 1,200 major combatant ships, including twenty-seven aircraft carriers and eight “fast” battleships, and ten prewar “old” battleships[6] totaling over 70% of the world’s total numbers and total tonnage of naval vessels of 1,000 tons or greater. On 16 June 1941, after negotiation with Churchill, Roosevelt ordered the United States occupation of Iceland to replace the British invasion forces. On 22 June 1941, the US Navy sent Task Force 19 (TF 19) from Charleston, South Carolina, to assemble at Argentia, Newfoundland. TF 19 included 25 warships and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade of 194 officers and 3714 men from San Diego, California under the command of Brigadier General John Marston. [9] Task Force 19 (TF 19) sailed from Argentia on 1 July. On 7 July, Britain persuaded the Althing to approve an American occupation force under a U. Icelandic defense agreement, and TF 19 anchored off Reykjavík that evening. Marines commenced landing on 8 July, and disembarkation was completed on 12 July. On 6 August, the U. Navy established an air base at Reykjavík with the arrival of Patrol Squadron VP-73 PBY Catalinas and VP-74 PBM Mariners. Army personnel began arriving in Iceland in August, and the Marines had been transferred to the Pacific by March, 1942. [9] Up to 40,000 U. Military personnel were stationed on the island, outnumbering adult Icelandic men at the time, Iceland had a population of about 120,000. The agreement was for the US military to remain until the end of the war (although the US military presence in Iceland remained through 2006). Main article: Attack on Pearl Harbor. After Pearl Harbor the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) seemed unstoppable because it outnumbered and outgunned the disorganized AlliesUS, Britain, Netherlands, Australia, China. London and Washington both believed in Mahanian doctrine, which stressed the need for a unified fleet. However, in contrast to the cooperation achieved by the armies, the Allied navies failed to combine or even coordinate their activities until mid-1942. Tokyo also believed in Mahan, who said command of the seasachieved by great fleet battleswas the key to sea power. Therefore, the IJN kept its main strike force together under Admiral Yamamoto and won a series of stunning victories over the Americans and British in the 90 days after Pearl Harbor. Outgunned at sea, the American strategy for victory required a holding action against the IJN until the much greater industrial potential of the US could be mobilized to build a fleet capable of projecting American power to the enemy heartland. Although most of the Battleships at Pearl Harbor were damaged, only the USS Arizona and the USS Oklahoma could not be repaired. It is often a misconception that the US Pacific fleet was “sunk” at Pearl Harbor. It is correct to say that American industrial might was a deciding factor in WWII, and Admiral Yamamoto knew that a prolonged war for Japan was a losing war. Main article: Battle of Midway. The Battle of Midway, together with the Guadalcanal campaign, marked the turning point in the Pacific. [10][11][12] Between June 47, 1942, the United States Navy decisively defeated a Japanese naval force that had sought to lure the U. Carrier fleet into a trap at Midway Atoll. The Japanese fleet lost four aircraft carriers to the U. Navy’s one American carrier and a destroyer. After Midway, and the exhausting attrition of the Solomon Islands campaign, Japan’s shipbuilding and pilot training programs were unable to keep pace in replacing their losses while the U. Steadily increased its output in both areas. Military historian John Keegan called the Battle of Midway the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare. Main article: Battle of Guadalcanal. Guadalcanal, fought from August 1942 to February 1943, was the first major Allied offensive of the war in the Pacific Theater. This campaign saw American air, naval and ground forces augmented by Australian and New Zealander forces in a six months campaign slowly overwhelm determined Japanese resistance. Guadalcanal was the key to control the Solomon Islands, which both sides saw as strategically essential. Both sides won some battles but both sides were overextended in terms of supply lines. The rival navies fought seven battles, with the two sides dividing the victories. They were: Battle of Savo Island, Battle of the Eastern Solomons, Battle of Cape Esperance, Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Battle of Tassafaronga and Battle of Rennell Island. Each of the sides pulled out its aircraft carriers, as they were too vulnerable to land-based aviation. In preparation of the recapture of the Philippines, the Allies started the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign to retake the Gilbert and Marshall Islands from the Japanese in summer 1943. Enormous effort went into recruiting and training sailors and Marines, and building warships, warplanes and support ships in preparation for a thrust across the Pacific, and to support Army operations in the Southwest Pacific, as well as in Europe and North Africa. The Navy continued its long movement west across the Pacific, seizing one island base after another. Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like the big bases at Truk, Rabaul and Formosa were neutralized by air attack and then simply leapfrogged. The ultimate goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks and finally an invasion. The US Navy did not seek out the Japanese fleet for a decisive battle, as Mahanian doctrine would suggest; the enemy had to attack to stop the inexorable advance. Battle of the Philippine Sea[edit]. Main article: Battle of the Philippine Sea. The carrier Zuikaku (center) and two destroyers under attack June 20, 1944. The climax of the carrier war came at the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Taking control of islands that could support airfields within B-29 range of Tokyo was the objective. 535 ships began landing 128,000 Army Soldiers and Marines on June 15, 1944 in the Mariana and Palau Islands. The achievement in planning such a complex logistical operation in just ninety days, and staging it 3,500 miles (5,600 km) from Pearl Harbor was indicative of American logistic superiority. The previous week an even bigger landing force hit the beaches of Normandyby 1944 the Allies had resources to spare. The Japanese launched an ill-coordinated attack on the larger American fleet; Japanese planes operated at extreme ranges and could not keep together, allowing them to be easily shot down in what Americans jokingly called the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. Japan had now lost all its offensive capabilities, and the U. Had control of Guam, Saipan and Tinian islands that provided air bases within range of B-29 bombers targeted at Japan’s home islands. It was entirely an air battle, in which Americans had all the technological advantages. It was the largest naval battle in history to date, surpassed only by the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. The American 5th Fleet covering the landing comprised 15 big carriers and 956 planes, plus 28 battleships and cruisers, and 69 destroyers. Tokyo sent Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa with nine-tenths of Japan’s fighting fleetit was about half the size of the American force, and included nine carriers with 473 planes, 18 battleships and cruisers, and 28 destroyers. Ozawa’s pilots boasted of their fiery determination, but they had only a fourth as much training and experience as the Americans. They were outnumbered 2-1 and used inferior equipment. Ozawa had anti-aircraft guns but lacked proximity fuzes and good radar. Ozawa gambled on surprise, luck and a trick strategy, but his battle plan was so complex and so dependent on good communications that it quickly broke down. His planes carried more gasoline because they were not weighted down with protective armor; they could attack at 300 miles (480 km), and could search a radius of 560 miles. [19] The heavier American Hellcats could only attack to 200 miles (320 km), and only search to 325. Ozawa’s plan therefore was to use his advantage in range by positioning his fleet 300 miles (480 km) out, forcing the Americans to search over 150,000 square miles (390,000 km2) of ocean just to find him. The Japanese ships would stay beyond American range, but their planes would have enough range to strike the American fleet. They would hit the carriers, land at Guam to refuel, then hit the Americans en route back to their carriers. Ozawa counted heavily on the 500 or so ground- based planes that had been flown ahead to Guam and other islands in the area. Main article: Battle of Okinawa. Okinawa was the last great battle of the entire war. The goal was to make the island into a staging area for the invasion of Japan scheduled for fall 1945. It was just 350 miles (550 km) south of the Japanese home islands. Marines and soldiers landed on 1 April 1945, to begin an 82-day campaign which became the largest land-sea-air battle in history and was noted for the ferocity of the fighting and the high civilian casualties with over 150,000 Okinawans losing their lives. Japanese kamikaze pilots enacted the largest loss of ships in U. Naval history with the sinking of 38 and the damaging of another 368. Casualties were over 12,500 dead and 38,000 wounded, while the Japanese lost over 110,000 men. The fierce combat and high American losses led the Navy to oppose an invasion of the main islands. An alternative strategy was chosen: using the atomic bomb to induce surrender. Technology and industrial power proved decisive. Japan failed to exploit its early successes before the immense potential power of the Allies could be brought to bear. In 1941, the Japanese Zero fighter had a longer range and better performance than rival American warplanes, and the pilots had more experience in the air. [21] But Japan never improved the Zero and by 1944 the Allied navies were far ahead of Japan in both quantity and quality, and ahead of Germany in quantity and in putting advanced technology to practical use. High tech innovations arrived with dizzying rapidity. Furthermore, older weapons systems were constantly upgraded and improved. Obsolescent airplanes, for example, received more powerful engines and more sensitive radar sets. One impediment to progress was that admirals who had grown up with great battleships and fast cruisers had a hard time adjusting their war-fighting doctrines to incorporate the capability and flexibility of the rapidly evolving new weapons systems. See also: List of ships of the Second World War. The ships of the American and Japanese forces were closely matched at the beginning of the war. By 1943 the American qualitative edge was winning battles; by 1944 the American quantitative advantage made the Japanese position hopeless. The Kriegsmarine, distrusting its Japanese ally, ignored Hitler’s orders to cooperate and failed to share its expertise in radar and radio. Thus the Imperial Navy was further handicapped in the technological race with the Allies (who did cooperate with each other). The United States economic base was ten times larger than Japan’s, and its technological capabilities also significantly greater, and it mobilized engineering skills much more effectively than Japan, so that technological advances came faster and were applied more effectively to weapons. Above all, American admirals adjusted their doctrines of naval warfare to exploit the advantages. The quality and performance of the warships of Japan were initially comparable to that of the US. The Americans were supremely, and perhaps overly, confident in 1941. Pacific commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz boasted he could beat a bigger fleet because of… Our superior personnel in resourcefulness and initiative, and the undoubted superiority of much of our equipment. As Willmott notes, it was a dangerous and ill-founded assumption. (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). The American battleships before Pearl Harbor could fire salvos of nine 2,100-pound armor-piercing shells every minute to a range of 35,000 yards (19 miles). Only another battleship had the thick armor that could withstand that kind of firepower. When intelligence reported that Japan had secretly built even more powerful battleships, Washington responded with four “Iowa” class battleships two of which were used a half-century later in the Gulf War. The “big-gun” admirals on both sides dreamed of a great shootout at twenty-mile (32 km) range, in which carrier planes would be used only for spotting the mighty guns. Their doctrine was utterly out of date. A plane like the Grumman TBF Avenger could drop a 2,000-pound bomb on a battleship at a range of hundreds of miles. An aircraft carrier cost less, required about the same number of personnel, was just as fast, and could easily sink a battleship. During the war the battleships found new missions: they were platforms holding all together dozens of anti-aircraft guns and 8 or 9 14″ or 16″ long-range guns used to blast land targets before amphibious landings. Their smaller 5″ guns, and the 4,800 3″ to 8 guns on cruisers and destroyers also proved effective at bombarding landing zones. After a short bombardment of Tarawa island in November 1943, Marines discovered that the Japanese defenders were surviving in underground shelters. It then became routine doctrine to thoroughly work over beaches with thousands of high-explosive and armor-piercing shells. The bombardment would destroy some fixed emplacements and kill some troops. More important, it severed communication lines, stunned and demoralized the defenders, and gave the landing parties fresh confidence. The sinking of the battleships at Pearl Harbor proved a blessing in deep disguise, for after they were resurrected and assigned their new mission they performed well. Absent Pearl Harbor, big-gun admirals like Raymond Spruance might have followed prewar doctrine and sought a surface battle in which the Japanese would have been very hard to defeat. [24] However, USN warships did enjoy a significant advantage over the IJN in terms of fire control, with even ships as small as destroyers being fitted with radar and ballistics computers. This advantage would prove decisive during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. In World War I the Navy explored aviation, both land-based and carrier based. However the Navy nearly abolished aviation in 1919 when Admiral William S. Benson, the reactionary Chief of Naval Operations, could not “conceive of any use the fleet will ever have for aviation”, and he secretly tried to abolish the Navy’s Aviation Division. [25] Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt reversed the decision because he believed aviation might someday be “the principal factor” at sea with missions to bomb enemy warships, scout enemy fleets, map mine fields, and escort convoys. Even Roosevelt, however, considered Billy Mitchell’s warnings of bombers capable of sinking battleships under wartime conditions to be “pernicious”. [26] Having failed in its attempt to rig a demonstration attack against the decommissioned USS Indiana, [27] the Navy was forced by Congressional resolutions to conduct more honest assessments. Despite rules of engagement again designed to enhance the survivability of the ships, [27][28] the tests went so badly against the ships that the Navy grudgingly continued to build up its aviation wing. In 1929, it had one carrier (USS Langley), 500 pilots and 900 planes; by 1937 it had 5 carriers (the Lexington, Saratoga, Ranger, Yorktown and Enterprise), 2000 pilots and 1000 much better planes. With Roosevelt now in the White House, the tempo soon quickened. One of the main relief agencies, the PWA, made building warships a priority. In 1941 the U. Navy with 8 carriers, 4,500 pilots and 3,400 planes had more airpower than the Japanese Navy. List of US Navy ships sunk or damaged in action during World War II. The item “SUPER WWII US Navy Archive Signed Photos etc Nimitz, Halsey, & Others USN” is in sale since Monday, January 15, 2018. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Militaria\WW II (1939-45)\Original Period Items\United States\Photographs”. The seller is “dalebooks” and is located in Rochester, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.