coach

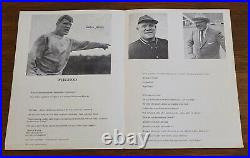

Coach Wally Weber 1969 Autograph University Michigan Wolverines Football Signed

FOLDOUR PROGRAM ; FOLDED MEASURES 8.5X11 INCHES. FEATURES A VERY RARE AUTOGRAPH OF FORMER COACH AND PLAYER WALLY WEBER. Inscribed to Bob Govell A great blocker for the Michigan Tradition Wally J Weber. Weber was an American football player and coach at the University of Michigan. He played halfback and fullback for the Wolverines in 1925 and 1926 on the same teams as Benny Friedman and Bennie Oosterbaan. He later became an assistant football coach at Michigan for 28 years from 1931 to 1958. As a player, coach, scout and raconteur, Wally Weber has furthered Michigan’s athletic tradition. A starter at fullback on Fielding Yost’s Big Ten champions in 1925 and 1926, Weber was known for his hard-hitting style of play on both sides of the ball. He was often assigned to stop the opponents’ biggest back, and when the Wolverines twice defeated Minnesota in 1926, Wally successfully shut down Gopher All-American Herb Joesting to lead the victories. Later, he took over coaching the freshmen and served as a scout. He coached under coaches Kipke, Crisler, Oosterbaan and Elliott and retired from the athletic department in 1973. Weber was a widely popular public speaker, preaching the merits of the Michigan athletic and academic tradition across the country. The Michigan Wolverines football team represents the University of Michigan in college football at the NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision level. Michigan has the most all-time wins in college football history. [2][3] The team is known for its distinctive winged helmet, its fight song, its record-breaking attendance figures at Michigan Stadium, [4] and its many rivalries, particularly its annual, regular season-ending game against Ohio State, known simply as “The Game, ” once voted as ESPN’s best sports rivalry. Michigan began competing in intercollegiate football in 1879. The Wolverines joined the Big Ten Conference at its inception in 1896, and other than a hiatus from 1907 to 1916, have been members since. Michigan has won or shared 42 league titles, and, since the inception of the AP Poll in 1936, has finished in the top 10 a total of 38 times. The Wolverines claim 11 national championships, most recently that of the 1997 squad voted atop the final AP Poll. From 1900 to 1989, Michigan was led by a series of nine head coaches, each of whom has been inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame either as a player or as a coach. Yost became Michigan’s head coach in 1901 and guided his “Point-a-Minute” squads to a streak of 56 games without a defeat, spanning from his arrival until the season finale in 1905, including a victory in the 1902 Rose Bowl, the first college football bowl game ever played. Fritz Crisler brought his winged helmet from Princeton University in 1938 and led the 1947 Wolverines to a national title and Michigan’s second Rose Bowl win. The first decade of his tenure was underscored by a fierce competition with his former mentor, Woody Hayes, whose Ohio State Buckeyes squared off against Schembechler’s Wolverines in a stretch of the Michigan-Ohio State rivalry dubbed the “Ten-Year War”. Following Schembechler’s retirement, the program was coached by two of his former assistants, Gary Moeller and then Lloyd Carr, who maintained the program’s overall success over the next 18 years. However, the program’s fortunes declined under the next two coaches, Rich Rodriguez and Brady Hoke, who were both fired after relatively short tenures. Following Hoke’s dismissal, Michigan hired Jim Harbaugh on December 30, 2014. [6] Harbaugh is a former quarterback of the team, having played for Michigan between 1982 and 1986 under Schembechler. The Michigan Wolverines have featured 83 players that have garnered consensus selection to the College Football All-America Team. Three Wolverines have won the Heisman Trophy: Tom Harmon in 1940, Desmond Howard in 1991, and Charles Woodson in 1997. Gerald Ford, who later became the 38th President of the United States, started at center and was voted most valuable player by his teammates on the 1934 team. Program records and achievements. Individual awards and honors. Team and conference MVP. Big Ten Conference honors. Hall of Fame inductees. College Football Hall of Fame. Pro Football Hall of Fame. Alumni in the NFL. See also: List of Michigan Wolverines football seasons. It has been suggested that portions of this section be split out into another article titled History of Michigan Wolverines football. Main article: History of Michigan Wolverines football in the early years. The 1879 squad, the first team fielded by the University. On May 30, 1879, Michigan played its first intercollegiate football game against Racine College at White Stocking Park in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune called it the first rugby-football game to be played west of the Alleghenies. “[7] Midway through “the first’inning’, [8] Irving Kane Pond scored the first touchdown for Michigan. [9][10] According to Will Perry’s history of Michigan football, the crowd responded to Pond’s plays with cheers of Pond Forever. [7] In 1881, Michigan played against Harvard in Boston. The game that marked the birth of inter-sectional football. [11] On their way to a game in Chicago in 1887, Michigan players stopped in South Bend, Indiana and introduced football to students at the University of Notre Dame. A November 23 contest marked the inception of the Notre Dame Fighting Irish football program and the beginning of the Michigan-Notre Dame rivalry. [12] In 1894, Michigan defeated Cornell, which was the first time in collegiate football history that a western school defeated an established power from the east. The 1898 Michigan Wolverines, the first Michigan team to win a conference title. In 1896, the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives-then commonly known as the Western Conference and later as the Big Ten Conference-was formed by the University of Michigan, the University of Chicago, the University of Illinois, the University of Minnesota, the University of Wisconsin, Northwestern University, and Purdue University. [14] The first Western Conference football season was played in 1896, with Michigan going 9-1, but losing out on the inaugural Western Conference title with a loss to the Chicago Maroons to end the season. By 1898 Amos Alonzo Stagg was fast at work at turning the University of Chicago football program into a powerhouse. Before the final game of the 1898 season, Chicago was 9-1-1 and Michigan was 9-0; a game between the two teams in Chicago decided the third Western Conference championship. Michigan won, 12-11, capturing the program’s first conference championship in a game that inspired “The Victors”, which later became the school’s fight song. [17] Michigan went 8-2 and 7-2-1 in 1899 and 1900, results that were considered unsatisfactory relative to the 10-0 season of 1898. Main article: History of Michigan Wolverines football in the Yost era. This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Please consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article’s talk page. Fielding Yost in 1902. After the 1900 season, Charles A. Baird, Michigan’s first athletic director, wrote to Fielding H. Yost, “Our people are greatly roused up over the defeats of the past two years”, and gave Yost an offer to come to Michigan to coach the football team. [19] Upon arriving at Michigan, Yost famously ran up State Street and proclaimed to a reporter, Michigan isn’t going to lose a game. [19] Yost certainly delivered, with the 1901 Michigan team demolishing its opponents. In the first season under head coach Yost, a lopsided victory over Buffalo drew national attention and marked the arrival of Yost’s “Point-a-Minute” teams. The Buffalo team beat Ivy League power Columbia earlier in the year and was favored over a Michigan team the Buffalo newspapers had dubbed Woolly Westerners. [20] Michigan scored 22 touchdowns in 38 minutes of play, averaging a touchdown every one minute and 43 seconds. Buffalo quit 15 minutes before the game was scheduled to end. [20] The New York Times reported that Michigan’s margin of victory was one of the most remarkable ever made in the history of football in the important colleges. [21] At the end of the season, Michigan participated in the inaugural Rose Bowl, the first bowl game in American football history. [22] Michigan dominated the game so thoroughly that Stanford’s captain requested the game be called with eight minutes remaining. Neil Snow scored five touchdowns in the game, which is still the all-time Rose Bowl record. [23] The Tournament of Roses Association held chariot races and other events in lieu of a football game for the next 15 years. The next year, 1902, featured a contest between Michigan and the Wisconsin Badgers. The two teams were undefeated since 1900, and the crowd (20,000-22,000) was the largest in western football history. Michigan won, 6-0, leading the Detroit Free Press to call it the greatest football game ever played on a western gridiron. [24] The undefeated 1902 team outscored its opponents 644 to 12 on its way to an 11-0 season. In 1903, Michigan played a game against Minnesota that started the rivalry for the Little Brown Jug, the oldest rivalry trophy in college football. After the game ended in a tie, Yost forgot the jug in the locker room. Custodian Oscar Munson discovered it and brought it to L. Cooke, who painted the jug brown and wrote Michigan Jug – Captured by Oscar, October 31, 1903. Michigan 6, Minnesota 6. [25] The game marked the only time from 1901 to 1904 that Michigan failed to win. [18] Michigan finished the season at 11-0-1. In 1904, Michigan once again went undefeated at 10-0 while recording one of the most lopsided defeats in college football history, a 130-0 defeat of the West Virginia Mountaineers. From 1901 through 1904, Michigan didn’t lose a single game. [18] The streak was finally halted at the end of the 1905 season by Amos Alonzo Stagg’s Chicago Maroons, a team that went on to win two Big 9 (as the Western Conference was now being called with the addition of Iowa and Indiana) titles in the next three years. [15] The game, dubbed “The First Greatest Game of the Century, “[26] broke Michigan’s 56-game unbeaten streak and marked the end of the “Point-a-Minute” years. The 1905 Michigan team had outscored opponents 495-0 in its first 12 games. The game was lost in the final ten minutes of play when Denny Clark was tackled for a safety as he attempted to return a punt from behind the goal line. Michigan tied for another Big 9 title in 1906 before opting to go independent for the 1907 season. The independent years were not as kind to Yost as his years in the Big 9. Michigan suffered one loss in 1907. [18] In 1908, Michigan got battered by Penn (a team that went 11-0-1 that year) in a game in which Michigan center Germany Schulz took such a battering as to have to be dragged off the field. [27] In 1909, Michigan suffered its first loss to Notre Dame, leading Yost to refuse to schedule another game against Notre Dame; the schools did not play again until 1942. [16] In 1910, Michigan played their only undefeated season of the independent years, going 3-0-3. [18] Overall from 1907 to 1916, Michigan lost at least one game every year (with the exception of 1910). Benny Friedman in 1929. Michigan rejoined the Big 9 in 1917, after which it was called the Big Ten. Yost immediately got back to work. In 1918, Michigan played the first game against Stagg’s Chicago Maroons since Chicago ended Michigan’s winning streak in 1905. [16] Michigan defeated the Maroons, 18-0, on the way to a 5-0 record. [16][18] The next three years were lean, with Michigan going 3-4, 5-2, and 5-1-1, in 1919, 1920, and 1921. [18] However, in 1922 Michigan managed to spoil the “Dedication Day” for Ohio Stadium, defeating the Buckeyes 19-0. [16] Legend has it that the rotunda at Ohio Stadium is painted with maize flowers on a blue background due to the outcome of the 1922 dedication game. [28] Michigan went 5-0-1 in 1922, capturing a Big Ten title. [15][18] In 1923, Michigan went 8-0, winning another conference championship. [15][18] The 1924 Wolverines, coached by George Little, saw their 20-game unbeaten streak end at the hands of Red Grange. [16] After the 1924 season, Little left Michigan to accept the head coach and athletic director positions at Wisconsin, returning athletic director Yost to the head coaching position. [29] Although the 1925 and 1926 seasons did not include a conference title, they were memorable due to the presence of the famous “Benny-to-Bennie” combination, a reference to Benny Friedman and Bennie Oosterbaan. The two helped popularize passing the ball in an era when running held dominance. Oosterbaan became a three-time All-American and was selected for the All-Time All-American team in 1951, [30] while Friedman went on to have a Hall of Fame NFL career. [31] Also during 1926, Michigan was retroactively awarded national titles for the 1901 and 1902 seasons via the Houlgate System, the first national titles awarded to the program. Other major selectorswho? Later retroactively awarded Michigan with titles in the 1903, 1904, 1918, 1923, 1925, and 1926 seasons. [citation needed] Michigan claims titles in the 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1918, and 1923 seasons. Yost stepped aside in 1926 to focus on being Michigan’s athletic director, a post he had held since 1921, thus ending the greatest period of success in the history of Michigan football. [33] Under Yost, Michigan posted a 165-29-10 record, winning ten conference championships and six national championships. [15][16][32] One of his main actions as athletic director was to oversee the construction of Michigan Stadium. Michigan began playing football games in Michigan Stadium in the fall of 1927. At the time Michigan Stadium had a capacity of 72,000, although Yost envisioned eventually expanding the stadium to a capacity well beyond 100,000. [34] Michigan Stadium was formally dedicated during a game against the Ohio State Buckeyes that season to the tune of a 21-0 victory. Tad Wieman became Michigan’s head coach in 1927. That year, Michigan posted a modest 6-2 record. [18] However, the team ended 1928 with a losing 3-4-1 record and Wieman was fired. Main article: History of Michigan Wolverines football in the Kipke years. In 1929, Harry Kipke, a former player under Yost, took over as head coach. During that stretch, Michigan won the Big Ten title every year and the national championship in 1932 and 1933. [15][32] In 1932, quarterback and future College Football Hall of Famer Harry Newman was a unanimous first-team All-American, and the recipient of the Douglas Fairbanks Trophy as Outstanding College Player of the Year (predecessor of the Heisman Trophy), and the Helms Athletic Foundation Player of the Year Award, the Chicago Tribune Silver Football trophy as the Most Valuable Player in the Big Ten Conference. [39] During this span Kipke’s teams only lost one game, to Ohio State. [16][18] After 1933, however, Kipke’s teams compiled a 12-22 record from 1934 to 1937. [18] The 1934 Michigan team only won one game, against Georgia Tech in a controversial contest. Georgia Tech coach and athletic director W. “Bill” Alexander refused to allow his team to take the field if Willis Ward, an African-American player for Michigan, stepped on the field. Michigan conceded, and the incident reportedly caused Michigan player Gerald R. Ford to consider quitting the team. [40] Overall, Kipke posted a 49-26-4 record at Michigan, winning four conference championships and two national championships. Main article: History of Michigan Wolverines football in the Crisler years. In 1938, Michigan hired Fritz Crisler as Kipke’s successor. [41] Crisler had been head coach of the Princeton Tigers and reportedly wasn’t excited to leave Princeton. [41] Michigan invited him to name his price, and Crisler demanded what he thought would be unacceptable: the position of athletic director when Yost stepped down and the highest salary in college football. [42] Michigan accepted, and Crisler became the new head coach of the Michigan football program. Fritz Crisler in 1948. Upon arriving at Michigan, Crisler introduced the winged football helmet, ostensibly to help his players find the receivers down field. [43] Whatever the reasoning, the winged helmet has since become one of the iconic marks of Michigan football. [44] Michigan debuted the winged helmet in a game against Michigan State in 1938. [45] Two years later in 1940, Tom Harmon led the Wolverines to a 7-1 record on his way to winning the Heisman Trophy. [18][46] Harmon ended the season by scoring three rushing touchdowns, two passing touchdowns, four extra points, intercepting three passes, and punting three times for an average of 50 yards in a game against the Ohio State Buckeyes. [47] The 1943 season included a No. 1 (Notre Dame) vs. 2 (Michigan) match-up against Notre Dame, a game the Wolverines lost 35-12. [16] Michigan ended the season at 8-1, winning Crisler’s first Big Ten championship. From 1938 to 1944, Michigan posted a 48-11-2 record, [48] although the period lacked a national title and only contained one conference title. [18] Yet, Crisler’s biggest mark on the game of football was made in 1945, when Michigan faced a loaded Army squad that featured two Heisman trophy winners, Doc Blanchard and Glenn Davis. Crisler didn’t feel that his Michigan team could match up with Army, so he opted to take advantage of a 1941 NCAA rule that allowed players to enter or leave at any point during the game. [42] Crisler divided his team into “offensive” and “defensive” specialists, an act that earned him the nickname the father of two-platoon football. [49] Michigan still lost the game with Army 28-7, [16] but Crisler’s use of two-platoon football shaped the way the game was played in the future. Eventually, Crisler’s use of the platoon system propelled his team to a conference championship and a national title in 1947, his final season. [15][16][32] The 1947 team, nicknamed the “Mad Magicians” due to their use of two-platoon football, capped their season with a 49-0 victory over the USC Trojans in the 1948 Rose Bowl. [16] Crisler finished with a 116-32-9 record at Michigan, winning two conference titles and one national title. [15][18][32][48]. Main article: History of Michigan Wolverines football in the Oosterbaan years. Crisler continued as athletic director while Bennie Oosterbaan, the same Bennie that had electrified the world while making connections with Benny Friedman 20 years earlier, took over the football program. [50] Things started off well for Oosterbaan in 1948 with the Wolverines earning a quality mid-season victory over No. [16][50] Michigan finished the season undefeated at 9-0, thus winning another national championship. [18][32] Initially, Oosterbaan continued Crisler’s tradition of on-field success, winning conference titles each year from 1948 to 1950 and the national title in 1948. [15][32] The 1950 season ended in interesting fashion, with Michigan and Ohio State combining for 45 punts in a game that came to be known as the Snow Bowl. Michigan won the game 9-3, winning the Big Ten conference and sending the Wolverines off to the 1951 Rose Bowl. [15][16] Subsequently, Michigan’s football team began to decline under Oosterbaan. From 1951 to 1958, Michigan compiled a record of 42-26-2, a far cry from the success under Crisler and Yost. [18] Perhaps more importantly, Oosterbaan posted a 2-5-1 record against Michigan State and a 3-5 record against Ohio State over the same time period. [16] Under mounting pressure, Oosterbaan stepped down after 1958. Main article: History of Michigan Wolverines football in the Elliott years. In place of Oosterbaan stepped Bump Elliott, a former Michigan player of Crisler’s. Elliott continued many of the struggles that began under Oosterbaan, posting a 51-42-2 record from 1959 through 1968 (including a 2-7-1 record against Michigan State and a 3-7 record against Ohio State). [18] Michigan’s only Big Ten title under Elliott came in 1964, a season that included a win over Oregon State in the 1965 Rose Bowl. [15][16] Following a 50-14 drubbing at the hands of Ohio State in 1968, [16] Elliott resigned, opening the way for Michigan athletic director Don Canham to hire Bo Schembechler. Bo Schembechler in 1975. Schembechler’s first team got off to a moderate start, losing to rival Michigan State and entering the Ohio State game with a 7-2 record. [18] Ohio State, coached by icon Woody Hayes, entered the game at 8-0 and poised to repeat as national champions. [53] The 1969 Ohio State team was hailed by some as being the “greatest college football team ever assembled” and came into the game favored by 17 points over Michigan. [54] Michigan shocked the Buckeyes, winning 24-12, going to the Rose Bowl, and launching The Ten Year War between Hayes and Schembechler. [16] From 1969 to 1978, one of either Ohio State or Michigan won at least a share of the Big Ten title and represented the Big Ten in the Rose Bowl every season. In 1970 Schembechler failed to repeat on the magic of 1969, that year losing to Ohio State 20-9 and finishing at 9-1. [16] However, in 1971, Schembechler led Michigan to an undefeated regular season, only to lose to the Stanford Indians in the Rose Bowl to finish at 11-1 and miss out on a chance at a national championship. [18] From 1972 to 1975, Michigan failed to win a game against Ohio State (powered by phenom running back Archie Griffin), finishing at 10-1, 10-0-1, 10-1, and 8-2-2. [16] However, Michigan did tie Ohio State in 1973, only missing out on the Rose Bowl due to a controversial vote that sent Ohio State to the Rose Bowl and left Michigan at home. [16] Another notable event occurred during the 1975 season, with the first of Michigan’s record streak of games with more than 100,000 people in attendance occurring during a game against the Purdue Boilermakers. Rick Leach, who played quarterback for Michigan from 1975 through 1978. From 1976 to 1978, Michigan asserted its own dominance of the rivalry, beating Ohio State, going to the Rose Bowl, and posting a 10-2 record every year. [16][18] After the 1978 season, Woody Hayes was fired for punching an opposing player during the 1978 Gator Bowl, thus ending The Ten Year War. [55] Michigan had a slight edge in the war, with Schembechler going 5-4-1 against Hayes. However, while Schembechler successfully placed great emphasis on the rivalry, Michigan’s bowl performances were sub-par. Michigan failed to win their last game of the season every year during The Ten Year War. [16] The only year in which Michigan didn’t lose its last game of the season was the 1973 tie against Ohio State. After the end of the Ten Year War, Michigan’s regular season performance declined, but its post season performance improved. The 1979 season included a memorable game against Indiana that ended with a touchdown pass from John Wangler to Anthony Carter with six seconds left in the game. [56] Michigan went 8-4 on the season, losing to North Carolina in the 1979 Gator Bowl. In 1980, Michigan went 10-2 and got their first win in the Rose Bowl under Schembechler, a 23-6 win over Washington. [16][18] Michigan went 9-3 in 1981 to get Schembechler’s second bowl win in the 1981 Bluebonnet Bowl. [16][18] In 1982, Michigan won the Big Ten championship while being led by three-time All-American wide receiver Anthony Carter. [15][57] Michigan fell to UCLA Bruins in the 1983 Rose Bowl. [16] Without Anthony Carter, the Wolverines did not win the Big Ten title in 1983, going 9-3. [18] In 1984, the Wolverines suffered their worst season under Schembechler, going 6-6 with a loss to national champion BYU in the 1984 Holiday Bowl. Michigan needed to reverse its fortunes in 1985, and they began doing so with new quarterback Jim Harbaugh. [58] Harbaugh led the Wolverines to a 5-0 record, propelling them to a No. 2 ranking heading into a game with the No. [59] Michigan lost 12-10, [16] but did not lose another game the rest of the season to finish at 10-1-1 with a victory over Tom Osborne’s Nebraska Cornhuskers in the 1986 Fiesta Bowl. [18] In 1986 Michigan won the Big Ten at 11-2, suffering a loss to the Arizona State Sun Devils in the 1987 Rose Bowl. The departure of Harbaugh after 1986 once again left Michigan on tough times as Schembechler’s team stumbled to an 8-4 record in 1987. [18] However, Michigan bounced back again in 1988 and 1989, winning the Big Ten title outright both years at 9-2-1 and 10-2 with trips to Rose Bowl. [15][18] From 1981 through 1989, Michigan went 80-27-2, winning four Big Ten titles and going to a bowl game every year (with another Rose Bowl win obtained against USC Trojans after the 1988 season). [16] Bo Schembechler retired after the 1989 season, handing the job over to his offensive coordinator Gary Moeller. [60] Under Schembechler, Michigan posted a 194-48-5 record[61] (11-9-1 against Ohio State), and won 13 Big Ten championships. Gary Moeller took over from Schembechler for the 1990 season, becoming the 16th head coach in Michigan football history. [62] Moeller inherited a talented squad that had just played in the 1990 Rose Bowl, including wide receiver Desmond Howard. [15][16] The next two years, Moeller’s teams won the conference outright, setting marks of 10-2 and 9-0-3. [15][18] In 1991, Desmond Howard had a memorable season that propelled him to win the Heisman Trophy, the award given to college football’s most outstanding player. [63] The 1992 team, led by quarterback Elvis Grbac, posted a 9-0-3 record, [18] defeating Washington in the 1993 Rose Bowl. [16] Moeller led Michigan to 8-4 records in both 1993 and 1994. [18] The 1994 season was marked by an early-season loss to Colorado that included a Hail Mary pass from Kordell Stewart to Michael Westbrook to end the game, leading to the game being dubbed The Miracle at Michigan. [64] After the 1994 season, Moeller was found intoxicated at a Southfield, MI restaurant in an incident in which Moeller was caught on tape throwing a punch in a police station, which resulted in his firing. Michigan’s athletic director appointed Lloyd Carr, an assistant at Michigan since 1980, as interim head coach for the 1995 season. [67] Michigan finished his first season at 9-4. [18][68] Carr had similar success in his second season, going 8-4 and earning a trip to the 1997 Outback Bowl. [69] Michigan went undefeated in 1997. [16][18] Overall, the Michigan defense only allowed 9.5 points per game and ended the season ranked No. 1 in the AP Poll, giving Michigan its first national championship since 1948 with a victory in the 1998 Rose Bowl. [70][71][16][32] For his efforts, Woodson won the Heisman Trophy and was selected 4th overall in the 1998 NFL Draft by the Oakland Raiders. With Tom Brady as quarterback, Michigan went 10-3 and repeated as Big Ten champions in 1998, but in 1999 Michigan lost out on the conference championship at 10-2 to the Wisconsin Badgers. [15][18] Drew Henson led Michigan to a 9-3 record and a tie for the Big Ten championship in 2000. Ohio State, Michigan’s chief rival, fired their coach John Cooper, who was 2-10-1 against Michigan while at Ohio State, after the 2000 season and replaced him with Jim Tressel. [73][74] Tressel immediately ushered in a new era in the Ohio State-Michigan rivalry, upsetting the Wolverines 26-20 in 2001, [75] his first season at the helm. [16] This came on the heels of another last-second loss in which Michigan State defeated Michigan with a pass in the last second of the game in a controversial finish that led to the game being referred to as Clockgate. [76] Despite these setbacks, Michigan’s 2001 squad, led by John Navarre, went 8-4 with an appearance in the 2002 Florida Citrus Bowl. [77][16][18] Again under Navarre in 2002, Michigan compiled a 10-3 record, [78] but included another loss to Ohio State, who went on to win the national championship. [79][16][18] Carr got over the hump against Tressel in 2003 as John Navarre and Doak Walker Award-winning running back Chris Perry led the Wolverines to a 10-3 record, [80] a Big Ten championship, and an appearance in the 2004 Rose Bowl. 2006 Michigan Wolverines huddle during a game against the Central Michigan Chippewas. For the 2004 season, Carr turned to highly rated recruit Chad Henne to lead the Wolverines at quarterback. [81] Michigan went 9-3 in 2004[82] to tie for another Big Ten championship and earn a trip to the 2005 Rose Bowl, but the season again included a loss to Ohio State, [83] who only went 8-4 on the season. In 2005, Michigan struggled to make a bowl game, only going 7-5, with the season capped with another loss to Ohio State. [16][18] Expectations were tempered going into the 2006 season; however, a 47-21 blowout of No. 2 Notre Dame and an 11-0 start propelled Michigan to the No. 2 rankings going into “The Game” with No. [84] The 2006 Ohio State-Michigan game was hailed by the media as the Game of the Century. The day before the game, Bo Schembechler died, leading Ohio State to honor him with a moment of silence, one of the few Michigan Men to be so honored in Ohio Stadium. [85] The game itself was a back-and-forth affair, with Ohio State winning 42-39 for the right to play in the 2007 BCS National Championship Game. [16] Michigan lost to USC in the 2007 Rose Bowl, ending the season at 11-2. Going into 2007, Michigan had high expectations. [86] Standout players Chad Henne, Mike Hart, and Jake Long all opted to return for their senior seasons for one last crack at Ohio State and a chance at a national championship, causing Michigan to be ranked fifth in the preseason polls. [87] However, Michigan’s struggles against the spread offense reared its ugly head again as the Wolverines shockingly lose the opener to the Appalachian State Mountaineers. [88][89][16] The game marked the first win by a Division I-AA team over a team ranked in the Associated Press Poll. [90] The next week, Michigan was blown out by Oregon. [91][16] Despite the early rough start, Michigan won their next eight games and went into the Ohio State game with a chance to win the Big Ten championship. [16] However, Michigan once again fell to the Buckeyes, this time 14-3. [92][16] After the game, Lloyd Carr announced that he would retire as Michigan head coach after the bowl game. [93] In the 2008 Capital One Bowl, Carr’s final game, Michigan defeated the defending national champion Florida Gators, led by Heisman Trophy winner Tim Tebow, 41-35. [94] Carr’s accomplishments at Michigan included a 122-40 record, five Big Ten championships, and one national championship. Rich Rodriguez at Michigan in 2008. Following Carr’s retirement, Michigan launched a coaching search that ultimately saw Rich Rodriguez lured away from his alma mater, West Virginia. [95] Rodriguez’s arrival marked the beginning of major upheaval in the Michigan football program. Rodriguez, a proponent of the spread offense, installed it in place of the pro-style offense that had been used by Carr. The offseason saw significant attrition in Michigan’s roster. The expected starting quarterback Ryan Mallett departed the program, stating that he would be unable to fit in a spread offense. Starting wide receivers Mario Manningham and Adrian Arrington both decided to forgo their senior seasons and enter the NFL Draft. [96] Michigan lost a good deal of its depth and, when the 2008 season began, was forced to start players with very little playing experience. The 2008 season was disappointing for Michigan, finishing at 3-9 and suffering its first losing campaign since 1967. Michigan also missed a bowl game invitation for the first time since 1974. For the 2009 season the team saw many changes from the previous year. A new practice facility replaced Oosterbaan Fieldhouse as Michigan’s indoor practice facility, [97] and two new quarterbacks, Tate Forcier and Denard Robinson, became the focus of the offseason. The week before the season began, however, the Detroit Free Press accused the team of violating the NCAA’s practice time limits. [98] While the NCAA conducted investigations, Michigan won its first four games, including a last second victory against its rival Notre Dame. The season ended in disappointment, however, as Michigan went 1-7 in its last eight games and missed a bowl for the second straight season. Rodriguez’s final season began with new hope in the program, as Robinson was named the starting quarterback over Forcier. Robinson led the Wolverines to a 5-0 start, but after a defeat to Michigan State at home, the Wolverines finished the season 2-5 over their last seven games. Michigan did, however, qualify for a bowl game with a 7-5 record, and clinched its bowl berth in dramatic fashion against Illinois, with Michigan winning 67-65 in three overtime periods. The game was the highest combined scoring game in Michigan history, and saw Michigan’s defense give up the most points in its history. [99] Michigan was invited to the Gator Bowl to face Mississippi State, losing 52-14. The Michigan defense set new school records as the worst defense in Michigan history. In the middle of the season, the NCAA announced its penalties against Michigan for the practice time violations. The program was placed on three of years probation and docked 130 practice hours, which was twice the amount Michigan had exceeded. Rodriguez was fired following the bowl game, with athletic director Dave Brandon citing Rodriguez’s failure to meet expectations as the main reason for his dismissal. [101] Rodriguez left the program winless against rivals Michigan State and Ohio State and compiled a 15-22 record, the worst record of any head coach in Michigan history. Athletic director Dave Brandon (left) with head coach Brady Hoke in 2011. Michigan announced the hiring of head coach Brady Hoke on January 11, 2011. [103] He became the 19th head coach in Michigan football history. Hoke had previously been the head coach at his alma mater Ball State and then San Diego State after serving as an assistant at Michigan under Lloyd Carr from 1995 to 2002. In his first season, Hoke led the Wolverines to 11 wins, beating rival Notre Dame with a spectacular comeback in Michigan’s first night game at Michigan Stadium. Despite losing to Iowa and Michigan State, the Wolverines finished with a 10-2 regular season record with their first win over Ohio State in eight years. The Wolverines received an invitation to the Sugar Bowl in which they defeated Virginia Tech, 23-20, in overtime. This was the program’s first bowl win since the season of 2007. Until the streak was broken in 2008, Michigan had appeared in a bowl game each year since the 1975 season. In Hoke’s second season, he led Michigan to an 8-5 record. The Wolverines dropped their season opener to eventual national champions, Alabama in Dallas, Texas. U-M won the next two games at home in non-conference bouts against Air Force and UMass, totaling 94 points over the two games. Michigan then traveled to face eventual national runner-up Notre Dame. In this game, the Wolverines committed six turnovers, including five interceptions, as they fell to the Fighting Irish by a 13-6 final. After back-to-back wins over Purdue and Illinois, they defeated in-state rival Michigan State for the first time since 2007. The win was the 900th in program history, becoming the first program to reach the milestone. U-M finished the season with wins over Minnesota, Northwestern and Iowa as well as losses to Nebraska and Ohio State to finish the regular season. Michigan was selected to participate in the 2013 Outback Bowl, where they fell to South Carolina by a 33-28 score. In the 2013 campaign, Michigan finished with a 7-6 record, including a 3-5 record in Big Ten play and a loss to Kansas State in the Buffalo Wild Wings Bowl 31-14. On December 2, 2014, Hoke was fired as the head coach after four seasons following a 5-7 record in 2014. This marked only the third season since 1975 in which Michigan missed a bowl game. Hoke compiled a 31-20 record, including an 18-14 record in Big Ten play. On December 30, 2014, the University of Michigan announced the hiring of Jim Harbaugh as the team’s 20th head coach. Harbaugh, who was starting quarterback in the mid-1980s under Bo Schembechler, had most recently served as head coach of the San Francisco 49ers. In his first season, Harbaugh led Michigan to a 10-3 record, including a 41-7 win over the Florida Gators in the 2016 Citrus Bowl. [106] The squad achieved an identical 10-3 record during the 2016 season, which ended with a 33-32 loss to Florida State in the Orange Bowl on December 30. The team lost many key players on the offensive and defensive side of the ball prior to Harbaugh’s third season. [107] Harbaugh’s fourth season started with a loss to rival Notre Dame, followed by ten consecutive wins. Wins over ranked Big Ten opponents Michigan State, Wisconsin, Penn State, all of whom beat Michigan the previous year, led to the team rallying around referring to the season as a revenge tour. “[108] The Wolverines rose to fourth in the College Football Playoff rankings, but the “revenge tour came to an abrupt end when they were upset by rival Ohio State by a lopsided score of 62-39 to end the regular season. Ohio State’s 62 points set a record for points against Michigan during regulation. A blowout loss to Florida in the Peach Bowl ended the season, and they finished at 10-3 for the third time in Harbaugh’s four years. During his fifth season (2019), the Wolverines lost to Wisconsin 35-14 and to Penn State 28-21, both on the road. Michigan went on to beat rivals Notre Dame 45-14 and Michigan State 44-10, but once again lost to then No. 1 ranked Ohio State by a score of 56-27 to end the regular season. Michigan later lost to Alabama 16-35 in the Citrus Bowl to end the season with a record of 9-4. For the 2020 season, -precautions delayed the start of Big10 play. The Wolverines started with a dominating win against Minnesota 49-24, however, in a highly physical game against Michigan State, the Wolverines incurred many player injuries and lost in a close score of 27-24. It proved to be the turning point of the season. The next week, playing many true freshmen, Michigan was thoroughly defeated by Indiana University 38-21. On November 14, 2020, Michigan hosted Wisconsin and Michigan suffered its largest halftime deficit at home since Michigan Stadium opened in 1927 (28-0), as well as its largest home loss (49-11) since 1935. [109][110] On November 28, 2020, Michigan hosted Penn State and for the first time in Michigan football history, lost to a team that was 0-5 or worse. [111] Michigan was winless at home during the 2020 season, marking the first time in program history that Michigan did not win any games at home. [112] The final three scheduled games of the season, against Maryland, Ohio State, and Iowa, were canceled due to -concerns. Again, Michigan failed to qualify for a postseason bowl game. The Athletic reported on December 22, 2020 that Michigan had fired its defensive coordinator, Don Brown, who had been on Harbaugh’s staff since the beginning of his tenure. Michigan finished the 2020 season with a record of 2-4 with sharply worse defensive statistics than in prior Brown-led defenses. The Michigan total defense was rated 2nd nationally in 2016 but was 59th overall in yards per play in 2020. On January 8, 2021, Jim Harbaugh signed a contract extension through 2025. Big Ten Conference (1917-present). Big Ten Conference (1953-present). Michigan has played in 48 bowl games in its history, compiling a record of 21-27. Before missing a bowl game in 2008, Michigan had made a bowl game 33 years in a row, the second longest streak (as of the end of 2013 season) in college football history. [114] From the 1921 to 1945 seasons, the Big Ten Conference did not allow its teams to participate in bowls. From the 1946 to 1974 seasons, only a conference champion, or a surrogate representative, was allowed to attend a bowl, the Rose Bowl, and no team could go two years in a row until the 1972 Rose Bowl, with the exception of Minnesota in 1961 and 1962. Hall of Fame Bowl. Buffalo Wild Wings Bowl. Bowl record by game. Citrus Bowl (Capital One Bowl). Outback Bowl (Hall of Fame Bowl). Main article: Washtenaw County Fairgrounds. In the early days of Michigan football, Michigan played smaller home games at the Washtenaw County Fairgrounds with larger games being held in Detroit at the Detroit Athletic Club. [115] The Fairgrounds were originally located at the southeast intersection of Hill and Forest, but in 1890 moved to what is now called Burns Park. Main article: Regents Field. Regents Field just before kickoff during the 1904 game between Michigan and Chicago. [116] Michigan began play on Regents Field in 1893, with capacity being expanded to over 15,000 by the end of the field’s use. Main article: Ferry Field. By 1902 Regents Field had grown inadequate for the uses of the football team as a result of the sport’s increasing popularity. [117] Thanks to donations from Dexter M. Ferry, work began on planning the next home stadium for the Michigan football team. [117] Ferry Field was expanded to a capacity of 21,000 in 1914 and 42,000 in 1921. [117] However, attendance was often over-capacity with crowds of 48,000 cramming into the small stadium. [117] This prompted athletic director Fielding Yost to contemplate the construction of a much larger stadium. Main article: Michigan Stadium. Michigan Stadium on September 17, 2011. Yost anticipated massive crowds as college football’s popularity increased and wished to build a stadium with a capacity of at least 80,000. [34] Ultimately, the final plans authorized the construction of a stadium with a capacity of 72,000 with footings to be set in place to expand it beyond 100,000 later. [34] Michigan Stadium was dedicated in 1927 during a game against the Ohio State Buckeyes, drawing an over-capacity crowd of 84,401. [118] After World War II, crowd sizes increased, prompting another stadium expansion to a capacity of 93,894 in 1949. [118] Michigan Stadium cracked the 100,000 mark by expanding to 101,001 in 1955. [118] Michigan Stadium temporarily lost the title of “largest stadium” to Neyland Stadium of the Tennessee Volunteers in 1996, but recaptured the title in 1998 with another expansion to 107,501. [121] This allowed Michigan to play its first night game at home against Notre Dame in 2011. Main article: Michigan-Ohio State football rivalry. Michigan and Ohio State first played each other in 1897. Ohio State’s victory in 2010 was vacated. The rivalry was particularly enhanced during The Ten Year War, a period in which Ohio State was coached by Woody Hayes and Michigan was coached by Bo Schembechler. Overall, the Buckeye and Wolverine football programs have combined for 19 national titles, 77 conference titles, and 10 Heisman Trophy winners. Michigan holds a 58-51-6 advantage through the 2019 season. Main article: Michigan-Michigan State football rivalry. Michigan and Michigan State first played each other in 1898. Since Michigan State joined the Big Ten Conference in 1953, the two schools have competed annually for the Paul Bunyan – Governor of Michigan Trophy. The winner retains possession of the trophy until the next year’s game. Michigan leads the trophy series 38-28-2. Michigan State is the holder of the trophy following a 2020 upset win over the heavily favored Wolverines, 27-24. Michigan holds a 71-37-5 advantage through the 2020 season. Main article: Michigan-Minnesota football rivalry. Michigan plays Minnesota for the Little Brown Jug trophy. The Little Brown Jug is the most regularly exchanged rivalry trophy in college football, the oldest trophy game in FBS college football, and the second oldest rivalry trophy overall. [125] Through the 2017 season, Michigan leads the overall series 75-25-3. Main article: Michigan-Notre Dame football rivalry. Michigan and Notre Dame began playing each other in 1887 in Notre Dame’s first football game. [127] The rivalry is notable due to the historical success of the football programs. Through the end of the 2017 season, Michigan is ranked No. 1 in wins and all-time winning percentage while Notre Dame is No. 2 in both categories. [128] Both schools also claim 11 national championships. [129] Michigan and Notre Dame have played in 42 contests, with Michigan holding a 25-17-1 advantage through the 2019 season. Main article: George Jewett Trophy. Michigan and Northwestern first played each other in 1892. In 2021, the two universities announced the creation of a new rivalry trophy to be awarded to the game’s winner, the George Jewett Trophy. The trophy honors George Jewett, the first African-American player in Big Ten Conference history, who played for both schools. The game is the first FBS rivalry game named for an African-American player. [131] Michigan holds a 58-15-2 advantage in the all-time series through the 2020 season. The following is a list of Michigan’s 11 national championships:[133]. Helms, Houlgate, NCF[134]. Billingsley, Helms, Houlgate, NCF, Parke Davis[134]. Dickinson, Parke Davis[134]. Berryman (QPRS), Billingsley, Boand, CFRA, Dickinson, Helms, Houlgate, NCF, Parke Davis, Poling, Sagarin[134]. Berryman (QPRS), Billingsley, Boand, CFRA, DeVold, Dunkel, Helms, Houlgate, Litkenhous, NCF, Poling, Sagarin[134]. AP, Berryman (QPRS), Billingsley, CFRA, DeVold, Dunkel, Helms, Houlgate, Litkenhous, NCF, Poling, Sagarin, Williamson[134]. AP, Billingsley, FWAA, NCF, NFF, Sporting News[134]. In addition to the 11 national championships that Michigan claims, the school has been named national champion by various “major selectors” featured in the NCAA record book for five other seasons. [134] Michigan does not claim national championships for these years. Michigan was also undefeated in 11 other seasons: 1879, 1880, 1884, 1885, 1886, 1887, 1898, 1910, 1922, 1930, 1992. The following is a list of Michigan’s 42 conference championships as of 2019. Michigan has shared one division title. N/A lost tiebreaker to Ohio State. Most wins in college football history (964)[137]. Most winning seasons of any program (120)[138]. Most appearances in the final AP Poll (61)[139]. Main article: List of Michigan Wolverines head football coaches. See also: Michigan Wolverines football statistical leaders. AFCA Coach of the Year. Paul “Bear” Bryant Award. Eddie Robinson Coach of the Year. Walter Camp Coach of the Year Award. Bobby Dodd Coach of the Year Award. Sporting News Coach of the Year. AFCA Assistant Coach of the Year. Twenty-six Heisman Trophy candidates have played at Michigan. Three have won the award. 1939: Tom Harmon, 2nd. 1940: Tom Harmon, 1st. 1941: Bob Westfall, 8th. 1943: Bill Daley, 7th. 1947: Bob Chappuis, 2nd. 1955: Ron Kramer, 8th. 1956: Ron Kramer, 6th. 1964: Bob Timberlake, 4th. 1968: Ron Johnson, 6th. 1974: Dennis Franklin, 8th. 1975: Gordon Bell, 8th. 1976: Rob Lytle, 3rd. 1977: Rick Leach, 8th. 1978: Rick Leach, 3rd. 1980: Anthony Carter, 10th. 1981: Anthony Carter, 7th. 1982: Anthony Carter, 4th. 1986: Jim Harbaugh, 3rd. 1991: Desmond Howard, 1st. 1993: Tyrone Wheatley, 8th. 1994: Tyrone Wheatley, 12th. 1995: Tim Biakabutuka, 8th. 1997: Charles Woodson, 1st. 2003: Chris Perry, 4th. 2004: Braylon Edwards, 10th. 2006: Mike Hart, 5th. 2010: Denard Robinson, 6th. 2016: Jabrill Peppers, 5th. Main article: List of Michigan Wolverines football All-Americans. 1926: Benny Friedman (also Big Ten MVP). 1932: Harry Newman (also Big Ten MVP). 1940: Tom Harmon (also Big Ten MVP). 1947: Bump Elliott (also Big Ten MVP). 1957: Jim Pace (also Big Ten MVP). 1964: Bob Timberlake (also Big Ten MVP). 1968: Ron Johnson (also Big Ten MVP). 1970: Henry Hill and Don Moorhead. 1976: Rob Lytle (also Big Ten MVP). 1978: Rick Leach (also Big Ten MVP). 1982: Anthony Carter (also Big Ten MVP). 1986: Jim Harbaugh (also Big Ten MVP). 1991: Desmond Howard (also Big Ten MVP). 1997: Charles Woodson (also Big Ten MVP). 2003: Chris Perry (also Big Ten MVP). 2004: Braylon Edwards (also Big Ten MVP). 2006: David Harris and Mike Hart. 2009: Brandon Graham (also Big Ten MVP). 2010: Denard Robinson (also Big Ten MVP). 2017: Maurice Hurst Jr. Player of the Year. Graham-George Offensive Player of the Year. 1990: Jon Vaughn (coaches). Rimington-Pace Offensive Lineman of the Year. Nagurski-Woodson Defensive Player of the Year. Smith-Brown Defensive Lineman of the Year. Thompson-Randle El Freshman of the Year. 1995: Charles Woodson (coaches). 1997: Anthony Thomas (coaches and media). 2003: Steve Breaston (coaches). 2004: Mike Hart (coaches and media). 2015: Jabrill Peppers (coaches and media). Dave McClain / Hayes-Schembechler Coach of the Year. 1972: Bo Schembechler (media). 1976: Bo Schembechler (media). 1980: Bo Schembechler (media). 1982: Bo Schembechler (coaches). 1985: Bo Schembechler (media and coaches). 1989: Bo Schembechler (coaches). 1991: Gary Moeller (media and coaches). 1992: Gary Moeller (media). 2011: Brady Hoke (media and coaches). Tatum-Woodson Defensive Back of the Year. Butkus-Fitzgerald Linebacker of the Year. Kwalick-Clark Tight End of the Year. Eddleman-Fields Punter of the Year. Rodgers-Dwight Return Specialist of the Year. The following jersey numbers have been retired by the program:[142]. Michigan Wolverines Retired Numbers. Beginning in 2011, previously retired numbers of “Michigan Football Legends” were assigned to and worn by players selected by the head coach. The Legends program was discontinued in July 2015, and the numbers again permanently retired. See also: College Football Hall of Fame. Michigan inductees into the College Football Hall of Fame as of 2021. Michigan inductees to the Pro Football Hall of Fame as of 2021. The Rose Bowl Hall of Fame has inducted the following Michigan players and coaches. Updated as of May 10, 2021. Ben Braden: Green Bay Packers. Tom Brady: Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Ben Bredeson: Baltimore Ravens. Devin Bush: Pittsburgh Steelers. Taco Charlton: Kansas City Chiefs. Camaron Cheeseman: Washington Football Team. Frank Clark: Kansas City Chiefs. Mason Cole: Minnesota Vikings. Nico Collins: Houston Texans. Mike Danna: Kansas City Chiefs. Chris Evans: Cincinnati Bengals. Nick Eubanks: Dallas Cowboys. Devin Funchess: Green Bay Packers. Rashan Gary: Green Bay Packers. Zach Gentry: Pittsburgh Steelers. Graham Glasgow: Denver Broncos. Ryan Glasgow: New Orleans Saints. Jordan Glasgow: Indianapolis Colts. Brandon Graham: Philadelphia Eagles. Chad Henne: Kansas City Chiefs. Lano Hill: Seattle Seahawks. Lavert Hill: Philadelphia Eagles. Khaleke Hudson: Washington Football Team. Maurice Hurst: San Francisco 49ers. Carlo Kemp: Green Bay Packers. Taylor Lewan: Tennessee Titans. Jourdan Lewis: Dallas Cowboys. David Long: Los Angeles Rams. Erik Magnuson: Las Vegas Raiders. Ben Mason: Baltimore Ravens. Jalen Mayfield: Atlanta Falcons. Cameron McGrone: New England Patriots. Sean McKeon: Dallas Cowboys. Josh Metellus: Minnesota Vikings. Bryan Mone: Seattle Seahawks. Quinn Nordin: New England Patriots. Michael Onwenu: New England Patriots. Kwity Paye: Indianapolis Colts. Donovan Peoples-Jones: Cleveland Browns. Jabrill Peppers: New York Giants. Cesar Ruiz: New Orleans Saints. Jon Runyan: Green Bay Packers. Brandon Rusnak: Jacksonville Jaguars. Ambry Thomas: San Francisco 49ers. Josh Uche: New England Patriots. Jarrod Wilson: Jacksonville Jaguars. Chase Winovich: New England Patriots. Chris Wormley: Pittsburgh Steelers. Announced schedules as of April 7, 2021. Weber (February 27, 1903 – April 14, 1984) was an American football player and coach at the University of Michigan. He continued to work for the University of Michigan in recruiting and alumni relations and as an instructor of physical education until his retirement in 1972. He also provided color commentary on WPAG radio’s broadcasts of Michigan football games with Bob Ufer. From 1927 to 1930, he was football coach at Benton Harbor High School, leading the Tigers to the state championship in 1929. He was inducted into the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor in 1981 as part of the fourth group of inductees. Only seven football players were inducted into the Hall of Honor before Weber. Football player at Michigan. Football coach at Benton Harbor. Football coach and raconteur at Michigan. Family and later years. A native of Mount Clemens, Michigan, [1] Weber played football at Michigan in 1925 and 1926 as a halfback and fullback in the same backfield with College and Pro Football Hall of Famer Benny Friedman and College Hall of Famer Bennie Oosterbaan. [2][3] In 1927, Weber scored two touchdowns against Wisconsin in Fielding H. Yost’s last game as Michigan’s football coach (also the last Michigan football game played at Ferry Field). Michigan won the game, 37-0. [4] The next week, Michigan played Ohio State in Columbus, and an anxious Weber was quoted as saying to Oosterbaan, Ben, at this rate they’re going to beat us 40-0. ” Oosterbaan reportedly replied, “Dammit, Wally, we haven’t had the ball yet. Having played with Friedman and Oosterbaan, Weber once modestly noted that my sole function in the drama was to inflate the ball. “[5] Weber later recalled that the 1925 and 1926 teams with Oosterbaan and Friedman helped build the demand for Michigan football: “We were so good, we created the demand for the new stadium. Ferry Field had a capacity of 45,000 and that wasn’t nearly big enough to handle the crowds who wanted to see us play. So they had to build the new stadium. In 1925 or 1926, a rule change was instituted so that players did not need to pursue a fumble out-of-bounds attempting to gain possession. During a game after the rule change, Weber reportedly scrambled after a fumble out-of-bounds, across the track surrounding the gridiron at Ferry Field. Weber scraped his face, hands and arms with the cinders from the track. When he handed the ball to an official, the official said, Weber, you dummy, don’t you know the rule changed this year and the ball belonged to Michigan when it went out of bounds? ” Weber replied, “Sure I knew, but I wasn’t sure you did. “[7] Asked in 1977 about how modern football players differed from his era, Weber conceded that modern players were bigger and stronger, yet noted: “But players had more stamina in the old football game. A Harmon played it all the way. An Oosterbaan played it all the way. A Weber played it all the way. Sixty minutes, no breaks. After graduating, Weber was a high school football coach for four years at Benton Harbor, Michigan from 1927 to 1930. [8] His team lost only one game in 1928 and won the state football championship in 1929, as the Weber machine swept through the entire campaign. [1] Weber coached future All-American Chuck Bernard in high school at Benton Harbor and later coached him in college at Michigan. [9] Another of Weber’s players from Benton Harbor, Art Buss, went on to play at Michigan State and in the NFL from 1934 to 1937 for the Chicago Bears and Philadelphia Eagles. When he left in 1931 to accept a job at Michigan, the Benton Harbor newspaper ran an article with a banner headline paying tribute to his accomplishments. In part, it noted. Wally’ Weber, former football star at the University of Michigan, today ends his successful and brilliant four year term as head coach of the Benton Harbor football team. Weber passes from Benton Harbor but his shouts of’Run, Run, Run,’ will always ring in the ears of his players and followers at Filstrup field. Wally came to Benton Harbor as a rookie coach, but leaves today as one of the greatest in the brilliant history of the gridiron sport at the local high school. Since coming here four years ago, Weber gave Benton Harbor its first state championship in 26 years. Weber is passing from Benton Harbor in body, but his loyal and winning spirit will never be forgotten here. Another article noted: Benton Harbor probably never has boasted a coach as popular as Coach Weber, who has really put Benton Harbor on the football map. “[1] On being invited to a reunion of his players in 1959, Weber recalled fondly his days as a high school football coach: “Your fine invitation to break bread with the athletes of yesteryear at Benton Harbor has fallen upon the ears of a grateful coach. Without some of those magnificent boys of’27-28-29-30 my life might have been entirely different. Those boys by their valiant deeds on the gridiron at Filstrup field encouraged me to take up coaching as a lifetime career. In 1931, Weber accepted a position as an assistant coach at Michigan and continued in that position for 28 years. Hercules Renda, a Michigan fullback in the late 1930s, said: Wally Weber was the ideal freshman coach. He would call you by the place you were from, and the state you were from. Think of the memory that man had? He would also use those big words. You were perfectly at ease with him at any time. When Weber stepped down as an assistant coach in 1958, he became a full-time recruiter for Michigan. [8] At the time, a Michigan sports columnist wrote of Weber: For 23 years Wally has blown the whistle on freshman football players. The polysyllabic Weber is Michigan’s foremost representative on the banquet circuit. In fact, he’s about the only one of the staff to get out and stump the state. “[8] His official position was public relations, which one paper said “in blunt terms means recruiting chief. In the 1950s and 1960s, Weber was a popular banquet speaker renowned for his “polysyllabic fluency, “[13] “mind–boggling after-dinner speeches, “[14] and his often humorous talks about the history of Michigan football. It was noted that he would “regale with dubious rhetoric” audiences before whom he would thunderously and whimsically “expatiate upon” Michigan’s storied history. [5] Another described Weber’s unusual speaking style this way: He still sounds like an educated foghorn, and still flips that king’s English around in a manner to amaze and apall old Noah Webster. “[15] Praising a piledriver spotted among a current crop of Wolverines, the coach would exclaim, “When he hits’em, generations yet unborn feel the shock of the impact! [5] Jim Brandstatter wrote in his book Tales from Michigan Stadium that Weber was still a regular visitor at the football offices when he enrolled in 1968. [12] He recalled Weber as a master story teller and a favorite among the students at pep rallies: Who can forget Wally Weber rolling his pant legs up to his knees as the student body roared before he spoke so eloquently about his beloved Michigan? [12] Weber also held positions in the 1960s and early 1970s in alumni relations and the physical education department. [14] Weber also provided color commentary on WPAG radio’s broadcasts of Michigan football games with Bob Ufer for several years. [16] He retired in 1972 at the same time as Oosterbaan. [14] With the exception of four years at Benton Harbor, Weber had been a student or employee of U-M for 48 years at the time of his retirement. Weber was married to Frances L. Enders of Benton Harbor. His wife died before him in July 1965. [17] They had a son, Robert Weber, who was a football coach at Kimball High School in Royal Oak, Michigan. Weber was inducted into the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor in 1981 as part of the fourth group of inductees. [18][19] Weber was still living in 1981 at the time of his induction into the Hall of Honor. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Autographs\Sports”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Uruguay.

- Modified Item: Yes

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Autographed Item: TESTIMONIAL DINNER

- Signed by: WALLY WEBER

- Sport: Football-NCAA

- Modification Description: SIGNED AND INSCRIBED

- Signed: Yes