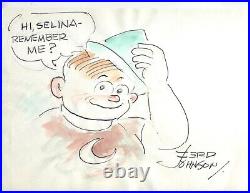

FERD JOHNSON SIGNED 8X11 VINTAGE ORIGINAL WATERCOLOR AND INK SKETCH SIGNE AND INSCRIBED. Ferdinand Johnson, usually cited as Ferd Johnson, was an American cartoonist, best known for his 68-year stint on the Moon Mullins comic strip. He was Frank Willard’s assistant and eventual successor on the comic strip Moon Mullins. Born December 18, 1905, in Spring Creek, Pennsylvania, Johnson became interested in cartooning after winning the Erie Pa. Dispatch-Herald cartoon contest at the age of 12. After finishing high school in 1923 he attended the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts but left school after only three months to take an assistant’s job at the Chicago Tribune with Frank Willard who had recently created the Moon Mullins comic strip. While assisting on Moon Mullins, Johnson remained active with other Tribune projects. In 1940 he revived Texas Slim in Texas Slim and Dirty Dalton (with the companion strip, Buzzy), which ran for 18 years. After Willard’s death in 1958 he took over full responsibility for Moon Mullins, which he continued to draw (assisted in later years by his son, Tom) until his retirement in 1991. Scope and Contents of the Collection. The Ferd Johnson Cartoons collection consists of. Daily cartoon: traces of graphite, blue pencil, opaque white, zipatone, pasteovers, brush, pen and ink on illustration board, approx. 6 x 17 ½ in. Sunday cartoon: traces of graphite, blue pencil, opaque white, pasteovers, brush, pen and ink on illustration board, approx. 17 x 24 ½ in. 10 ½ x 24 in. Sunday cartoon: traces of graphite, brush, pen and ink on illustration board, approx. 5 ½ x 23 ½ in. Arrangement of the Collection. Cartoons are arranged by title in chronological order. Daily and Sunday cartoons are housed separately. The majority of our archival and manuscript collections are housed offsite and require advanced notice for retrieval. Written permission must be obtained from SCRC and all relevant rights holders before publishing quotations, excerpts or images from any materials in this collection. Other original Moon Mullins strips may be found in the Frank Willard Cartoons. Special Collections Research Center has collections of over eighty cartoonists. Please refer to the SCRC Subject Index for a complete listing. Moon Mullins is an American comic strip which had a run as both a daily and Sunday feature from June 19, 1923 to June 2, 1991. Syndicated by the Chicago Tribune/New York News Syndicate, the strip depicts the lives of diverse lowbrow characters who reside at the Schmaltz (later Plushbottom) boarding house. The central character, Moon (short for Moonshine), is a would-be prizefighter-perpetually strapped for cash but with a roguish appetite for vice and high living. Moon took a room in the boarding house at 1323 Wump Street in 1924 and never left, staying on for 67 years. The strip was created by cartoonist Frank Willard. Comic books and reprints. Kayo Mullins chocolate drink. Frank Henry Willard was born on September 21, 1893, in Anna, Illinois, [citation needed] the son of a physician, [citation needed] who early on determined to become a cartoonist. After attending the Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago in 1913, [citation needed] he was a staff artist with the Chicago Herald (1914-18), where he drew the Sunday kids’ page Tom, Dick and Harry and another strip, Mrs. [citation needed] He next wrote and drew The Outta Luck Club for King Features Syndicate (1919-23). In The Comics (1947), Coulton Waugh described Willard’s art style as gritty-looking. [1] In 2003, the Scoop newsletter documented the 1923 events that led to the creation of the strip. Moon was a tough-talking, if generally good natured, kind of guy who took (and dealt) plenty of punches during his run. And actually, those are very appropriate characteristics. See, back before Moon was created, Frank Willard was working on a strip called The Outta Luck Club for King Features Syndicate. That’s when he got the notion that some of his ideas were being slipped to fellow cartoonist George McManus (creator of Bringing Up Father). So, in typical Moon Mullins fashion, Willard approached McManus and gave him a wallop that knocked the latter out cold and got the former fired. That little episode didn’t stop Captain Joe Patterson’s interest from being piqued, however, and Willard soon set to work on a new strip for the Chicago Tribune Syndicate. That strip was Moon Mullins.. He made a horrible role model but a hilarious star nonetheless-as did his assorted pals… Adventures included stints in jail, trysts with stolen cars, failed employment opportunities, misunderstandings and plenty of black eyes for all. Yet, there was a certain lightness to all of Moon’s debaucheries that made his low-down ways pretty charming… Willard was in tune with the working class characters he created, as noted by David Westbrook in From Hogan’s Alley to Coconino County: Four Narratives of the Early Comic Strip. Some comic strip artists laid claim to a similar working-class authenticity by representing themselves in the position of employee. When Frank Willard, author of Moon Mullins, narrates a scene from his workplace, he portrays himself as a rowdy underdog much like The Yellow Kid. He becomes, in effect, the “tricky and roguish” character cited by Gilbert Seldes as the quintessence of the comic strip. I worked for a syndicate manager once who got everybody in the place together once a week and jumped on a desk and gave us’pep talks. He didn’t give us ideas, but, oh boy, how worn out we were after those pep talks. When Brennecke (in “The Real Mission of the Funny Paper” by Ernest Brennecke, from The Century Magazine, March 1924) locates the truth of comic strip realism in the comics’ habit of “commenting trenchantly” on “the life of the middle classes, ” it is comics like The Yellow Kid and artists like Willard that he has in mind… Moon Mullins: With his big eyes, plaid pants, perpetual cigar and yellow derby hat, Moon is an amiable roughneck. He haunts saloons, racetracks and pool halls, mangles the English language with Jazz Age slang, and gets into endless scrapes looking for an easy buck or a hot dame. Moon himself is a low-rent but likeable sort of riff-raff, involved in get-rich schemes and bootleg whiskey, crap games and staying out all night with disreputable friends. None of the roughhousing was fatal or even particularly threatening, however. Indeed, the gentleness of the situational humor behind all the characters’ rough edges kept the strip on an even keel. The name “Moonshine” referenced Mullins as a drinker and gambler during Prohibition. Kayo: Moon’s street urchin kid brother, who sleeps in an open dresser drawer. Kayo is usually clad in suspenders, polka dot pants and a black derby. Pint-sized Kayo a play on K. Sportswriters’ shorthand for a knockout punch is wise beyond his years and even a bit of a cynic. His plain-speaking, matter-of-fact bluntness is a frequent source of comedy. Moon Mullins #2 (February-March 1948) displayed reprints of the comic strip. Emmy (Schmaltz) Plushbottom: the nosy, lanky, spinsterish landlady who likes to put on airs. She finally married on October 6, 1933 and became Lady Plushbottom. (Uncle) Willie: Introduced in 1927, Moon’s long lost, no-account uncle wears a checkered suit and is perpetually unshaven. Willie, who would disappear for months at a time, prefers the hobo life-despite being married and half-domesticated. His only occupation seems to be the avoidance of physical labor and confrontations with his formidable wife, Mamie. (Aunt) Mamie: Miss Schmaltz’s burly, no-nonsense washwoman and cook. Her rolled-up sleeves reveal a conspicuous star tattoo. She’s the only featured character of the working class cast who actually works. Mamie is usually tolerant of her errant husband, but she can be dangerous when riled-much to Willie’s dismay. Lord Plushbottom: aka “Plushie, ” as Moon calls him. Willard introduced him because Patterson thought tossing a well-bred Englishman into that shabby crowd had great comic possibilities. [citation needed] Plushbottom initially appeared as a man of wealth, whom Emmy pursued for 10 years before their marriage. Afterward he moved in, in apparently reduced circumstances, but never discarded his evening clothes, spats and top hat for everyday wear. Egypt: Emmy’s beautiful flapper niece with the bobbed Louise Brooks coiffure, and Moon’s sometime girlfriend. Mushmouth: Moon’s pal and much-maligned step-and-fetch-it. Kitty Higgins: the star of Willard’s “topper” strip about a precocious little girl and her maid, Pauline. Kitty eventually joined the Moon Mullins cast as Kayo’s girlfriend. After Johnson took over, other characters were added to the cast, including. Professor Byrrd: an erudite, tweed-suited academic. Myna Byrrd: the Professor’s lovely brunette daughter. Miss Swivel: a sexy blonde stenographer, frequently pursued by Moon. Doodle: an eccentric, temperamental artist. Joke: a cab driver. The strip was reviewed by Dr. It was never so hysterical that you felt you just had to clip it and show it to everyone you knew, but Moon Mullins was always enjoyable and funny in a low-key way. Frank Willard’s art was better than it’s given credit for, very smooth and subtle; but his real strength was in the amusing personalities he gave his characters. Longtime assistant Ferd Johnson took over after Willard’s death in 1958. “Moonshine” Mullins, as his name hinted, was a shady sort of rogue, always in trouble and often in jail. His little brother Kayo was a tough guy in a derby and turtleneck; everyone remembers him as the kid who slept in a pulled-out dresser drawer. Running the boarding house was sour ol’ Emmy Schmaltz she later married insubstantial Englishman Lord Plushbottom. Rounding out the continuing cast were the cook Mamie and her less than industrious husband Willie. Moon Mullins is not likely to be adapted into the new big Broadway musical (although you never know), but I always liked it and would like to see it remembered. The Sunday page’s topper strip, Kitty Higgins, ran from December 14, 1930 to 1973. Ferd Johnson’s Moon Mullins (January 3, 1959). When Willard died suddenly on January 11, 1958, the Tribune Syndicate hired Johnson to helm the strip. Johnson’s first credited strip ran on March 3, 1958. Frank Willard’s tombstone at the Anna Cemetery in Anna, Illinois, is graced with an engraving of Moon Mullins. Ferd Johnson was born December 18, 1905, in Spring Creek, Pennsylvania. [citation needed] Johnson became interested in cartooning after winning the Erie (Pennsylvania) Dispatch-Herald cartoon contest at the age of 12. [citation needed] After finishing high school in 1923 he attended the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, but left school after only three months to take an assistant’s job at the Chicago Tribune with Willard. [citation needed] While assisting on Moon Mullins, Johnson remained active with other Tribune projects. In 1940, he revived Texas Slim in Texas Slim and Dirty Dalton (with the companion strip, Buzzy), which ran for 18 years. By the time he took Moon Mullins, it had evolved from long story continuities to a gag-a-day strip. In 1978, Ferd’s son, Tom Johnson, signed on as his assistant. Ferd Johnson stayed with the strip until it came to an end upon his retirement in 1991. Frank Willard’s Moon Mullins (March 3, 1942). Moon Mullins appeared in 350 papers at its height but declined to 50. Johnson said, [citation needed] They just kept dropping off because it’s so damn old. The new ones come out and the editors want to make room for them, so the old ones get dumped. And Moon sure qualifies that way. In April 1991, the Chicago Tribune dropped the strip, and the Tribune Media Syndicate told Johnson that it was the end. [7] The last strip ran on Sunday, 2 June 1991. This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: “Moon Mullins” – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). Dover Publications reprinted a collection of the daily strips in 1976, consisting of the third and fifth Cupples & Leon books. Representative samples of Moon Mullins daily continuity were featured in Great Comics Syndicated by the Daily News-Chicago Tribune (Crown Publishers, 1972), and The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics (Smithsonian Institution Press/Harry Abrams, 1977). The latter volume also reproduces several full-color Sunday pages. Moon Mullins merchandising[8] began when agent Toni Mendez arranged a licensing deal for Kayo suspenders. The wave of products that followed included such items as a series of Kellogg’s Pep Cereal pins, a Milton Bradley board game (1938), salt and pepper shakers, perfume bottles, Christmas lights, bisque toothbrush holders, a set of German nodder figures, carnival chalkware statues, a wind-up toy handcar, oilcloth and celluloid Kayo dolls, coloring books and a series of jigsaw puzzles (1943). Kayo Chocolate Drink was the name of a bottled, later canned, [9] chocolate-flavored milk drink. Created in 1929 by Aaron D. Pashkow of Chicago, [10][11] it was bottled under authority of Chocolate Products, manufactured for decades, [12] and featured Kayo Mullins on its label. In 1973, the Moon Mullins radio program was issued on this LP produced by George Garabedian for Mark 56 Records. The sleeve notes were by radio historian Jim Harmon. Moon Mullins was adapted for radio during the 1940s. In the third episode of the series (March 25, 1940), the Plushbottoms trade Moon’s only suit to pay for a collect telegram and learn they are owners of a goldmine. Lord Plushbottom plans to go to a costume party as an Indian but instead winds up with a suit of armor. Character actor Sheldon Leonard was in the cast. Cambria Studios produced two sample episodes of a proposed Moon Mullins syndicated TV series with their Syncro-Vox animation process in the early 1960s, but it didn’t clear enough television stations to go into production. Moon and Kayo became one of several rotating segments on the Saturday morning cartoon series. Other comic strip character features in the rotation included Broom-Hilda, Dick Tracy, The Captain and the Kids, Alley Oop, Nancy and Sluggo and Smokey Stover. It was repeated in 1978, without Archie, under the title Fabulous Funnies. When Ferd Johnson was thirteen years old, he won a gold watch for drawing cartoons for a railroad station agents’ magazine. He studied at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. He got a job at the Chicago Tribune, coloring Sunday pages of Frank Willard’s’Moon Mullins’. In 1925, Ferd Johnson drew his own Sunday page,’Texas Slim’. In 1932, he created another,’Lovey-Dovey’. His great break came in 1940, when he revived Texas Slim in a strip called’Texas Slim and Dirty Dalton’. This popular cowboy comedy ran for eighteen years, until the death of Frank Willard, after which Johnson took over’Moon Mullins’. He worked on this strip with his son Tom until his retirement in 1991. Ferd Johnson died in 1996. Ferdinand Johnson (December 18, 1905 – October 14, 1996), usually cited as Ferd Johnson, was an American cartoonist, best known for his 68-year stint on the Moon Mullins comic strip. Johnson was born December 18, 1905, in Spring Creek, Pennsylvania, [1] and had a younger brother, George. [citation needed] Johnson’s youthful interest in cartooning had the support of his family after he won an Erie Dispatch Herald cartoon contest. He recalled in 1989, I think I was 11 years old. I went through that and worked on the high school yearbook all the time. I did lots of drawings there. After graduating from high school in 1923, he attended the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts for three months. [1] When Moon Mullins creator Frank Willard taught briefly there, Willard invited the talented youngster to visit his workplace, The Chicago Tribune. Johnson recalled, I stood around there for hours watching him work. He finally turned around and said,’Ferd, if you’re going to hang around here all this time, I’m going to put you to work. So I got a job as assistant at 15 bucks a week. I’ve got it made. [3] Dropping out of school, he became Willard assistant two months after Willard launched Moon Mullins in 1923. [1] Johnson worked at the Tribune as a color artist and sports illustrator. While Johnson was still in his teens, the paper offered him the opportunity to create his own comic strip. Johnson’s effort, Texas Slim, about a ranch hand working for the antihero Dirty Dalton, debuted as a Sunday page from the Tribune Syndicate on August 30, 1925. It ran three years, until February 12, 1928. [4] Starting October 4, 1931, Johnson revived Texas Slim as a topper strip paired with his short-lived domestic-comedy strip Lovey Dovey. The topper lasted until September 11, 1932; Lovey Dovey held on until September 25, 1933. This strip had its own topper, Buzzy, which ran from 1943 to 1953. Willard and Johnson traveled to Florida, Maine and Los Angeles, doing Moon Mullins while living in hotels, apartments and farmhouses. At its peak of popularity during the 1940s and 1950s, the strip ran in 350 newspapers. According to Johnson, he had been doing the strip solo for at least a decade before Willard’s death on January 11, 1958. “They put my name on it then”, Johnson said in 1989. I had been doing it about 10 years before that because Willard had heart attacks and strokes and all that stuff. The minute my name went on that thing and his name went off, 25 papers dropped the strip. That shows you that, although I had been doing it 10 years, the name means a lot. After Willard’s death, the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate hired Johnson as Willard’s logical successor, and he began signing the strip. Johnson recalled that,”Texas [Slim & Dirty Dalton] ran until 1958 when I took over Moon completely. Up to then I was working on both Moon and Texas and some advertising work, and taking some time off to eat and sleep. He stayed with the strip until it concluded in June 1991. [1] In 1978, [citation needed] his son, Tom Johnson, signed on as his assistant[1] (drawing the Sunday page and assisting on the dailies). [citation needed] Ferd Johnson worked on Moon Mullins for 68 years, a stint that comics historian Don Markstein calls probably the longest in the history of American comics. Johnson continued to draw and paint after he moved into a retirement home in Irvine, California in 1995, [citation needed] and he died 15 months later. [citation needed] Doris, his wife of 57 years, whom he met in art school in Chicago, died in 1986. Ferd Johnson received a ComicCon International Inkpot Award in 1993. A comic strip is a sequence of drawings, often cartoon, arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, with text in balloons and captions. Traditionally, throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, these have been published in newspapers and magazines, with daily horizontal strips printed in black-and-white in newspapers, while Sunday papers offered longer sequences in special color comics sections. With the advent of the internet, online comic strips began to appear as webcomics. Strips are written and drawn by a comics artist, known as a cartoonist. As the word “comic” implies, strips are frequently humorous. Examples of these gag-a-day strips are Blondie, Bringing Up Father, Marmaduke, and Pearls Before Swine. In the late 1920s, comic strips expanded from their mirthful origins to feature adventure stories, as seen in Popeye, Captain Easy, Buck Rogers, Tarzan, and Terry and the Pirates. In the 1940s, soap-opera-continuity strips such as Judge Parker and Mary Worth gained popularity. Because “comic” strips are not always funny, cartoonist Will Eisner has suggested that sequential art would be a better genre-neutral name. Every day in American newspapers, for most of the 20th century, there were at least 200 different comic strips and cartoon panels, which makes 73,000 per year. [2] Comic strips have appeared inside American magazines such as Liberty and Boys’ Life, but also on the front covers, such as the Flossy Frills series on The American Weekly Sunday newspaper supplement. In the UK and the rest of Europe, comic strips are also serialized in comic book magazines, with a strip’s story sometimes continuing over three pages or more. Social and political influence. Rights to the strips. Storytelling using a sequence of pictures has existed through history. One medieval European example in textile form is the Bayeux Tapestry. Printed examples emerged in 19th-century Germany and in 18th-century England, where some of the first satirical or humorous sequential narrative drawings were produced. William Hogarth’s 18th century English cartoons include both narrative sequences, such as A Rake’s Progress, and single panels. The Biblia pauperum (“Paupers’ Bible”), a tradition of picture Bibles beginning in the later Middle Ages, sometimes depicted Biblical events with words spoken by the figures in the miniatures written on scrolls coming out of their mouths-which makes them to some extent ancestors of the modern cartoon strips. In China, with its traditions of block printing and of the incorporation of text with image, experiments with what became lianhuanhua date back to 1884. The first newspaper comic strips appeared in North America in the late 19th century. [4] The Yellow Kid is usually credited as one of the first newspaper strips. However, the art form combining words and pictures developed gradually and there are many examples which led up to the comic strip. The Glasgow Looking Glass was the first mass-produced publication to tell stories using illustrations and is regarded as the worlds first comic strip. It satirised the political and social life of Scotland in the 1820s. Conceived and illustrated by William Heath. His illustrated stories such as Histoire de M. Vieux Bois (1827), first published in the USA in 1842 as The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck or Histoire de Monsieur Jabot (1831), inspired subsequent generations of German and American comic artists. In 1865, German painter, author, and caricaturist Wilhelm Busch created the strip Max and Moritz, about two trouble-making boys, which had a direct influence on the American comic strip. Max and Moritz was a series of seven severely moralistic tales in the vein of German children’s stories such as Struwwelpeter (“Shockheaded Peter”). In the story’s final act, the boys, after perpetrating some mischief, are tossed into a sack of grain, run through a mill, and consumed by a flock of geese (without anybody mourning their demise). Max and Moritz provided an inspiration for German immigrant Rudolph Dirks, [5] who created the Katzenjammer Kids in 1897 – a strip starring two German-American boys visually modelled on Max and Moritz. Familiar comic-strip iconography such as stars for pain, sawing logs for snoring, speech balloons, and thought balloons originated in Dirks’ strip. When Dirks left William Randolph Hearst for the promise of a better salary under Joseph Pulitzer, it was an unusual move, since cartoonists regularly deserted Pulitzer for Hearst. In a highly unusual court decision, Hearst retained the rights to the name “Katzenjammer Kids”, while creator Dirks retained the rights to the characters. Hearst promptly hired Harold Knerr to draw his own version of the strip. Dirks renamed his version Hans and Fritz (later, The Captain and the Kids). Thus, two versions distributed by rival syndicates graced the comics pages for decades. Dirks’ version, eventually distributed by United Feature Syndicate, ran until 1979. In the United States, the great popularity of comics sprang from the newspaper war (1887 onwards) between Pulitzer and Hearst. The Little Bears (1893-96) was the first American comic strip with recurring characters, while the first color comic supplement was published by the Chicago Inter-Ocean sometime in the latter half of 1892, followed by the New York Journal’s first color Sunday comic pages in 1897. On January 31, 1912, Hearst introduced the nation’s first full daily comic page in his New York Evening Journal. [7] The history of this newspaper rivalry and the rapid appearance of comic strips in most major American newspapers is discussed by Ian Gordon. [8] Numerous events in newspaper comic strips have reverberated throughout society at large, though few of these events occurred in recent years, owing mainly to the declining use of continuous storylines on newspaper comic strips, which since the 1970s had been waning as an entertainment form. [9] From 1903 to 1905 Gustave Verbeek, wrote his comic series “The UpsideDowns of Old Man Muffaroo and Little Lady Lovekins”. These comics were made in such a way that one could read the 6 panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. He made 64 such comics in total. The longest-running American comic strips are. Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Barney Google and Snuffy Smith (1919-present). Some newspaper strips begin or remain exclusive to one newspaper. For example, the Pogo comic strip by Walt Kelly originally appeared only in the New York Star in 1948 and was not picked up for syndication until the following year. Newspaper comic strips come in two different types: daily strips and Sunday strips. Daily strips usually are printed in black and white, and Sunday strips are usually in color. However, a few newspapers have published daily strips in color, and some newspapers have published Sunday strips in black and white. While in the early 20th century comic strips were a frequent target for detractors of “yellow journalism”, by the 1920s the medium became wildly popular. While radio, and later, television surpassed newspapers as a means of entertainment, most comic strip characters were widely recognizable until the 1980s, and the “funny pages” were often arranged in a way they appeared at the front of Sunday editions. In 1931, George Gallup’s first poll had the comic section as the most important part of the newspaper, with additional surveys pointing out that the comic strips were the second most popular feature after the picture page. During the 1930s, many comic sections had between 12 and 16 pages, although in some cases, these had up to 24 pages. The popularity and accessibility of strips meant they were often clipped and saved; authors including John Updike and Ray Bradbury have written about their childhood collections of clipped strips. Often posted on bulletin boards, clipped strips had an ancillary form of distribution when they were faxed, photocopied or mailed. The Baltimore Sun’s Linda White recalled, I followed the adventures of Winnie Winkle, Moon Mullins and Dondi, and waited each fall to see how Lucy would manage to trick Charlie Brown into trying to kick that football. After I left for college, my father would clip out that strip each year and send it to me just to make sure I didn’t miss it. The two conventional formats for newspaper comics are strips and single gag panels. The strips are usually displayed horizontally, wider than they are tall. Single panels are square, circular or taller than they are wide. Strips usually, but not always, are broken up into several smaller panels with continuity from panel to panel. A horizontal strip can also be used for a single panel with a single gag, as seen occasionally in Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grimm. Early daily strips were large, often running the entire width of the newspaper, and were sometimes three or more inches high. [14] Initially, a newspaper page included only a single daily strip, usually either at the top or the bottom of the page. By the 1920s, many newspapers had a comics page on which many strips were collected together. During the 1930s, the original art for a daily strip could be drawn as large as 25 inches wide by six inches high. [15] Over decades, the size of daily strips became smaller and smaller, until by 2000, four standard daily strips could fit in an area once occupied by a single daily strip. [14] As strips have become smaller, the number of panels have been reduced. Proof sheets were the means by which syndicates provided newspapers with black-and-white line art for the reproduction of strips (which they arranged to have colored in the case of Sunday strips). Michigan State University Comic Art Collection librarian Randy Scott describes these as large sheets of paper on which newspaper comics have traditionally been distributed to subscribing newspapers. Typically each sheet will have either six daily strips of a given title or one Sunday strip. Thus, a week of Beetle Bailey would arrive at the Lansing State Journal in two sheets, printed much larger than the final version and ready to be cut apart and fitted into the local comics page. [16] Comic strip historian Allan Holtz described how strips were provided as mats (the plastic or cardboard trays in which molten metal is poured to make plates) or even plates ready to be put directly on the printing press. He also notes that with electronic means of distribution becoming more prevalent printed sheets are definitely on their way out. NEA Syndicate experimented briefly with a two-tier daily strip, Star Hawks, but after a few years, Star Hawks dropped down to a single tier. In Flanders, the two-tier strip is the standard publication style of most daily strips like Spike and Suzy and Nero. [19] They appear Monday through Saturday; until 2003 there were no Sunday papers in Flanders. [20] In the last decades, they have switched from black and white to color. Main article: Panel (comics). Jimmy Hatlo’s They’ll Do It Every Time was often drawn in the two-panel format as seen in this 1943 example. Single panels usually, but not always, are not broken up and lack continuity. The daily Peanuts is a strip, and the daily Dennis the Menace is a single panel. Williams’ long-run Out Our Way continued as a daily panel even after it expanded into a Sunday strip, Out Our Way with the Willets. Jimmy Hatlo’s They’ll Do It Every Time was often displayed in a two-panel format with the first panel showing some deceptive, pretentious, unwitting or scheming human behavior and the second panel revealing the truth of the situation. Main article: Sunday comics. Gene Ahern’s The Squirrel Cage (January 3, 1937), an example of a topper strip which is better remembered than the strip it accompanied, Ahern’s Room and Board. Russell Patterson and Carolyn Wells’ New Adventures of Flossy Frills (January 26, 1941), an example of comic strips on Sunday magazines. Sunday newspapers traditionally included a special color section. Early Sunday strips (known colloquially as “the funny papers”, shortened to “the funnies”), such as Thimble Theatre and Little Orphan Annie, filled an entire newspaper page, a format known to collectors as full page. Sunday pages during the 1930s and into the 1940s often carried a secondary strip by the same artist as the main strip. No matter whether it appeared above or below a main strip, the extra strip was known as the topper, such as The Squirrel Cage which ran along with Room and Board, both drawn by Gene Ahern. During the 1930s, the original art for a Sunday strip was usually drawn quite large. For example, in 1930, Russ Westover drew his Tillie the Toiler Sunday page at a size of 17″ × 37″. [21] In 1937, the cartoonist Dudley Fisher launched the innovative Right Around Home, drawn as a huge single panel filling an entire Sunday page. Full-page strips were eventually replaced by strips half that size. Strips such as The Phantom and Terry and the Pirates began appearing in a format of two strips to a page in full-size newspapers, such as the New Orleans Times Picayune, or with one strip on a tabloid page, as in the Chicago Sun-Times. When Sunday strips began to appear in more than one format, it became necessary for the cartoonist to allow for rearranged, cropped or dropped panels. During World War II, because of paper shortages, the size of Sunday strips began to shrink. After the war, strips continued to get smaller and smaller because of increased paper and printing costs. The last full-page comic strip was the Prince Valiant strip for 11 April 1971. Comic strips have also been published in Sunday newspaper magazines. Russell Patterson and Carolyn Wells’ New Adventures of Flossy Frills was a continuing strip series seen on Sunday magazine covers. Beginning January 26, 1941, it ran on the front covers of Hearst’s American Weekly newspaper magazine supplement, continuing until March 30 of that year. Between 1939 and 1943, four different stories featuring Flossy appeared on American Weekly covers. Sunday comics sections employed offset color printing with multiple print runs imitating a wide range of colors. Printing plates were created with four or more colors-traditionally, the CMYK color model: cyan, magenta, yellow and “K” for black. With a screen of tiny dots on each printing plate, the dots allowed an image to be printed in a halftone that appears to the eye in different gradations. The semi-opaque property of ink allows halftone dots of different colors to create an optical effect of full-color imagery. The decade of the 1960s saw the rise of underground newspapers, which often carried comic strips, such as Fritz the Cat and The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Zippy the Pinhead initially appeared in underground publications in the 1970s before being syndicated. [24] Bloom County and Doonesbury began as strips in college newspapers under different titles, and later moved to national syndication. Underground comic strips covered subjects that are usually taboo in newspaper strips, such as sex and drugs. Many underground artists, notably Vaughn Bode, Dan O’Neill, Gilbert Shelton, and Art Spiegelman went on to draw comic strips for magazines such as Playboy, National Lampoon, and Pete Millar’s CARtoons. Jay Lynch graduated from undergrounds to alternative weekly newspapers to Mad and children’s books. Webcomics, also known as online comics and internet comics, are comics that are available to read on the Internet. Many are exclusively published online, but the majority of traditional newspaper comic strips have some Internet presence. King Features Syndicate and other syndicates often provide archives of recent strips on their websites. This section may contain indiscriminate, excessive, or irrelevant examples. Please improve the article by adding more descriptive text and removing less pertinent examples. See Wikipedia’s guide to writing better articles for further suggestions. Most comic strip characters do not age throughout the strip’s life, but in some strips, like Lynn Johnston’s award-winning For Better or For Worse, the characters age as the years pass. The first strip to feature aging characters was Gasoline Alley. The history of comic strips also includes series that are not humorous, but tell an ongoing dramatic story. Examples include The Phantom, Prince Valiant, Dick Tracy, Mary Worth, Modesty Blaise, Little Orphan Annie, Flash Gordon, and Tarzan. Sometimes these are spin-offs from comic books, for example Superman, Batman, and The Amazing Spider-Man. A number of strips have featured animals as main characters. Some are non-verbal (Marmaduke, The Angriest Dog in the World), some have verbal thoughts but are not understood by humans, (Garfield, Snoopy in Peanuts), and some can converse with humans (Bloom County, Calvin and Hobbes, Mutts, Citizen Dog, Buckles, Get Fuzzy, Pearls Before Swine, and Pooch Cafe). Other strips are centered entirely on animals, as in Pogo and Donald Duck. Gary Larson’s The Far Side was unusual, as there were no central characters. Instead The Far Side used a wide variety of characters including humans, monsters, aliens, chickens, cows, worms, amoebas, and more. John McPherson’s Close to Home also uses this theme, though the characters are mostly restricted to humans and real-life situations. Wiley Miller not only mixes human, animal, and fantasy characters, but also does several different comic strip continuities under one umbrella title, Non Sequitur. Bob Thaves’s Frank & Ernest began in 1972 and paved the way for some of these strips, as its human characters were manifest in diverse forms – as animals, vegetables, and minerals. The comics have long held a distorted mirror to contemporary society, and almost from the beginning have been used for political or social commentary. This ranged from the conservative slant of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie to the unabashed liberalism of Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury. Al Capp’s Li’l Abner espoused liberal opinions for most of its run, but by the late 1960s, it became a mouthpiece for Capp’s repudiation of the counterculture. Pogo used animals to particularly devastating effect, caricaturing many prominent politicians of the day as animal denizens of Pogo’s Okeefenokee Swamp. In a fearless move, Pogo’s creator Walt Kelly took on Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, caricaturing him as a bobcat named Simple J. Malarkey, a megalomaniac who was bent on taking over the characters’ birdwatching club and rooting out all undesirables. Kelly also defended the medium against possible government regulation in the McCarthy era. At a time when comic books were coming under fire for supposed sexual, violent, and subversive content, Kelly feared the same would happen to comic strips. Going before the Congressional subcommittee, he proceeded to charm the members with his drawings and the force of his personality. The comic strip was safe for satire. During the early 20th century, comic strips were widely associated with publisher William Randolph Hearst, whose papers had the largest circulation of strips in the United States. Hearst was notorious for his practice of yellow journalism, and he was frowned on by readers of The New York Times and other newspapers which featured few or no comic strips. Hearst’s critics often assumed that all the strips in his papers were fronts for his own political and social views. Hearst did occasionally work with or pitch ideas to cartoonists, most notably his continued support of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. An inspiration for Bill Watterson and other cartoonists, Krazy Kat gained a considerable following among intellectuals during the 1920s and 1930s. Some comic strips, such as Doonesbury and Mallard Fillmore, may be printed on the editorial or op-ed page rather than the comics page because of their regular political commentary. For example, the August 12, 1974 Doonesbury strip was awarded a 1975 Pulitzer Prize for its depiction of the Watergate scandal. Dilbert is sometimes found in the business section of a newspaper instead of the comics page because of the strip’s commentary about office politics, and Tank McNamara often appears on the sports page because of its subject matter. Lynn Johnston’s For Better or for Worse created an uproar when Lawrence, one of the strip’s supporting characters, came out of the closet. The world’s longest comic strip is 88.9-metre (292 ft) long and on display at Trafalgar Square as part of the London Comedy Festival. [27] The London Cartoon Strip was created by 15 of Britain’s best known cartoonists and depicts the history of London. The Reuben, named for cartoonist Rube Goldberg, is the most prestigious award for U. Reuben awards are presented annually by the National Cartoonists Society (NCS). In 1995, the United States Postal Service issued a series of commemorative stamps, Comic Strip Classics, marking the comic-strip centennial. Today’s strip artists, with the help of the NCS, enthusiastically promote the medium, which since the 1970s (and particularly the 1990s) has been considered to be in decline due to numerous factors such as changing tastes in humor and entertainment, the waning relevance of newspapers in general and the loss of most foreign markets outside English-speaking countries. One particularly humorous example of such promotional efforts is the Great Comic Strip Switcheroonie, held in 1997 on April Fool’s Day, an event in which dozens of prominent artists took over each other’s strips. Garfield’s Jim Davis, for example, switched with Blondie’s Stan Drake, while Scott Adams (Dilbert) traded strips with Bil Keane (The Family Circus). While the 1997 Switcheroonie was a one-time publicity stunt, an artist taking over a feature from its originator is an old tradition in newspaper cartooning (as it is in the comic book industry). In fact, the practice has made possible the longevity of the genre’s more popular strips. Examples include Little Orphan Annie (drawn and plotted by Harold Gray from 1924 to 1944 and thereafter by a succession of artists including Leonard Starr and Andrew Pepoy), and Terry and the Pirates, started by Milton Caniff in 1934 and picked up by George Wunder. A business-driven variation has sometimes led to the same feature continuing under a different name. In one case, in the early 1940s, Don Flowers’ Modest Maidens was so admired by William Randolph Hearst that he lured Flowers away from the Associated Press and to King Features Syndicate by doubling the cartoonist’s salary, and renamed the feature Glamor Girls to avoid legal action by the AP. The latter continued to publish Modest Maidens, drawn by Jay Allen in Flowers’ style. As newspapers have declined, the changes have affected comic strips. Jeff Reece, lifestyle editor of The Florida Times-Union, wrote, Comics are sort of the’third rail’ of the newspaper. In the early decades of the 20th century, all Sunday comics received a full page, and daily strips were generally the width of the page. The competition between papers for having more cartoons than the rest from the mid-1920s, the growth of large-scale newspaper advertising during most of the thirties, paper rationing during World War II, the decline on news readership (as television newscasts began to be more common) and inflation (which has caused higher printing costs) beginning during the fifties and sixties led to Sunday strips being published on smaller and more diverse formats. As newspapers have reduced the page count of Sunday comic sections since the late 1990s (by the 2010s, most sections have only four pages, with the back page not always being destined for comics) has also led to further downsizes. Daily strips have suffered as well. Before the mid-1910s, there wasn’t a “standard” size, with strips running the entire width of a page or having more than one tier. By the 1920s, strips often covered six of the eight columns occupied by a traditional broadsheet paper. During the 1940s, strips were reduced to four columns wide (with a “transition” width of five columns). As newspapers became narrower beginning in the 1970s, strips have gotten even smaller, often being just three columns wide, a similar width to the one most daily panels occupied before the 1940s. In an issue related to size limitations, Sunday comics are often bound to rigid formats that allow their panels to be rearranged in several different ways while remaining readable. Such formats usually include throwaway panels at the beginning, which some newspapers will omit for space. As a result, cartoonists have less incentive to put great efforts into these panels. Garfield and Mutts were known during the mid-to-late 80s and 1990s respectively for their throwaways on their Sunday strips, however both strips now run “generic” title panels. Some cartoonists have complained about this, with Walt Kelly, creator of Pogo, openly voicing his discontent about being forced to draw his Sunday strips in such rigid formats from the beginning. Kelly’s heirs opted to end the strip in 1975 as a form of protest against the practice. Since then, Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson has written extensively on the issue, arguing that size reduction and dropped panels reduce both the potential and freedom of a cartoonist. After a lengthy battle with his syndicate, Watterson won the privilege of making half page-sized Sunday strips where he could arrange the panels any way he liked. Many newspaper publishers and a few cartoonists objected to this, and some papers continued to print Calvin and Hobbes at small sizes. Opus won that same privilege years after Calvin and Hobbes ended, while Wiley Miller circumvented further downsizes by making his Non Sequitur Sunday strip available only in a vertical arrangement. Actually, most strips created since 1990 are drawn in the unbroken “third-page” format. Few newspapers still run half-page strips, as with Prince Valiant and Hägar the Horrible in the front page of the Reading Eagle Sunday comics section until the mid-2010s. With the success of The Gumps during the 1920s, it became commonplace for strips (comedy- and adventure-laden alike) to have lengthy stories spanning weeks or months. The “Monarch of Medioka” story in Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse comic strip ran from September 8, 1937 to May 2, 1938. Between the 1960s and the late 1980s, as television news relegated newspaper reading to an occasional basis rather than daily, syndicators were abandoning long stories and urging cartoonists to switch to simple daily gags, or week-long “storylines” with six consecutive (mostly unrelated) strips following a same subject, with longer storylines being used mainly on adventure-based and dramatic strips. Strips begun during the mid-1980s or after (such as Get Fuzzy, Over the Hedge, Monty, and others) are known for their heavy use of storylines, lasting between one and three weeks in most cases. The writing style of comic strips changed as well after World War II. With an increase in the number of college-educated readers, there was a shift away from slapstick comedy and towards more cerebral humor. Slapstick and visual gags became more confined to Sunday strips, because as Garfield creator Jim Davis put it, Children are more likely to read Sunday strips than dailies. Many older strips are no longer drawn by the original cartoonist, who has either died or retired. Such strips are known as “zombie strips”. A cartoonist, paid by the syndicate or sometimes a relative of the original cartoonist, continues writing the strip, a tradition that became commonplace in the early half of the 20th century. Hägar the Horrible and Frank and Ernest are both drawn by the sons of the creators. Some strips which are still in affiliation with the original creator are produced by small teams or entire companies, such as Jim Davis’ Garfield, however there is some debate if these strips fall in this category. This act is commonly criticized by modern cartoonists including Watterson and Pearls Before Swine’s Stephan Pastis. The issue was addressed in six consecutive Pearls strips in 2005. [29] Charles Schulz, of Peanuts fame, requested that his strip not be continued by another cartoonist after his death. He also rejected the idea of hiring an inker or letterer, comparing it to a golfer hiring a man to make his putts. Schulz’s family has honored his wishes and refused numerous proposals by syndicators to continue Peanuts with a new author. Since the consolidation of newspaper comics by the first quarter of the 20th century, most cartoonists have used a group of assistants (with usually one of them credited). However, quite a few cartoonists e. George Herriman and Charles Schulz, among others have done their strips almost completely by themselves; often criticizing the use of assistants for the same reasons most have about their editors hiring anyone else to continue their work after their retirement. Historically, syndicates owned the creators’ work, enabling them to continue publishing the strip after the original creator retired, left the strip, or died. This practice led to the term “legacy strips, ” or more pejoratively “zombie strips”. Most syndicates signed creators to 10- or even 20-year contracts. There have been exceptions, however, such as Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff being an early-if not the earliest-case in which the creator retained ownership of his work. Both these practices began to change with the 1970 debut of Universal Press Syndicate, as the company gave cartoonists a 50-percent ownership share of their work. Creators Syndicate, founded in 1987, granted artists full rights to the strips, [30] something that Universal Press did in 1990, followed by King Features in 1995. By 1999 both Tribune Media Services and United Feature had begun granting ownership rights to creators (limited to new and/or hugely popular strips). Starting in the late 1940s, the national syndicates which distributed newspaper comic strips subjected them to very strict censorship. Li’l Abner was censored in September 1947 and was pulled from the Pittsburgh Press by Scripps-Howard. The controversy, as reported in Time, centered on Capp’s portrayal of the U. Said Edward Leech of Scripps, We don’t think it is good editing or sound citizenship to picture the Senate as an assemblage of freaks and crooks… As comics are easier for children to access compared to other types of media, they have a significantly more rigid censorship code than other media. Stephan Pastis has lamented that the “unwritten” censorship code is still “stuck somewhere in the 1950s”. Generally, comics are not allowed to include such words as “damn”, “sucks”, “screwed”, and “hell”, although there have been exceptions such as the September 22, 2010 Mother Goose and Grimm in which an elderly man says, “This nursing home food sucks, ” and a pair of Pearls Before Swine comics from January 11, 2011 with a character named Ned using the word “crappy”. [32][33][34] Naked backsides and shooting guns cannot be shown, according to Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams. [35] Such comic strip taboos were detailed in Dave Breger’s book But That’s Unprintable (Bantam, 1955). Many issues such as sex, narcotics, and terrorism cannot or can very rarely be openly discussed in strips, although there are exceptions, usually for satire, as in Bloom County. This led some cartoonists to resort to double entendre or dialogue children do not understand, as in Greg Evans’ Luann. Another example of wordplay to get around censorship is a July 27, 2016 Pearls Before Swine strip that features Pig talking to his sister, and says the phrase I SIS! Repeatedly after correcting his sister’s grammar. The strip then cuts to a scene of a NSA wiretap agent, following a scene of Pig being arrested by the FBI saying “Never correct your sister’s grammar”, implying that the CIA mistook the phrase “I SIS” with “ISIS”. [citation needed] Younger cartoonists have claimed commonplace words, images, and issues should be allowed in the comics, considering that the pressure on “clean” humor has been a chief factor for the declining popularity of comic strips since the 1990s (Aaron McGruder, creator of The Boondocks, decided to end his strip partly because of censorship issues, while the Popeye daily comic strip ended in 1994 after newspapers objected to a storyline they considered to be a satire on abortion). Some of the taboo words and topics are mentioned daily on television and other forms of visual media. Webcomics and comics distributed primarily to college newspapers are much freer in this respect. Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. History of American comics. List of British comic strips. List of newspaper comic strips. Military humor comic strips.