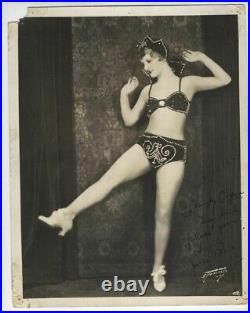

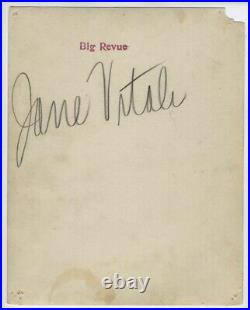

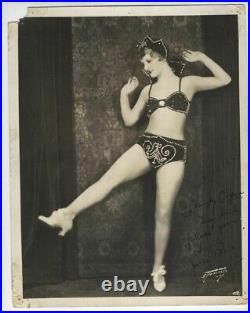

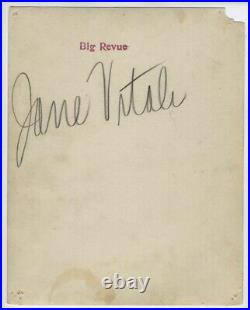

Jane Vitale extremely rare signed Burlesque c1920’s 8×10 inch photo from BIG REVUE. Burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. [1] The word derives from the Italian burlesco, which, in turn, is derived from the Italian burla – a joke, ridicule or mockery. [2] Burlesque overlaps in meaning with caricature, parody and travesty, and, in its theatrical sense, with extravaganza, as presented during the Victorian era. [3] “Burlesque” has been used in English in this literary and theatrical sense since the late 17th century. It has been applied retrospectively to works of Chaucer and Shakespeare and to the Graeco-Roman classics. [4] Contrasting examples of literary burlesque are Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock and Samuel Butler’s Hudibras. An example of musical burlesque is Richard Strauss’s 1890 Burleske for piano and orchestra. Examples of theatrical burlesques include W. Gilbert’s Robert the Devil and the A. Torr – Meyer Lutz shows, including Ruy Blas and the Blasé Roué. A later use of the term, particularly in the United States, refers to performances in a variety show format. These were popular from the 1860s to the 1940s, often in cabarets and clubs, as well as theatres, and featured bawdy comedy and female striptease. Some Hollywood films attempted to recreate the spirit of these performances from the 1930s to the 1960s, or included burlesque-style scenes within dramatic films, such as 1972’s Cabaret and 1979’s All That Jazz, among others. There has been a resurgence of interest in this format since the 1990s. Contents [hide] 1 Literary origins and development 2 Burlesque in music 2.1 Classical music 2.2 Jazz 3 Victorian theatrical burlesque 4 American burlesque 5 Notes 6 References 7 External links. Literary origins and development[edit]. Arabella Fermor, target of The Rape of the Lock The word first appears in a title in Francesco Berni’s Opere burlesche of the early 16th century, works that had circulated widely in manuscript before they were printed. For a time, burlesque verses were known as poesie bernesca in his honour. Burlesque’ as a literary term became widespread in 17th century Italy and France, and subsequently England, where it referred to a grotesque imitation of the dignified or pathetic. [7] Shakespeare’s Pyramus and Thisbe scene in Midsummer Night’s Dream and the general mocking of romance in Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle were early examples of such imitation. [8] In 17th century Spain, playwright and poet Miguel de Cervantes ridiculed medieval romance in his many satirical works. Among Cervantes’ works are Exemplary Novels and the Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes published in 1615. [9] The term burlesque has been applied retrospectively to works of Chaucer and Shakespeare and to the Graeco-Roman classics. [4] Burlesque was intentionally ridiculous in that it imitated several styles and combined imitations of certain authors and artists with absurd descriptions. In this, the term was often used interchangeably with “pastiche”, “parody”, and the 17th and 18th century genre of the “mock-heroic”. [10] Burlesque depended on the reader’s (or listener’s) knowledge of the subject to make its intended effect, and a high degree of literacy was taken for granted. [11] 17th and 18th century burlesque was divided into two types: High burlesque refers to a burlesque imitation where a literary, elevated manner was applied to a commonplace or comically inappropriate subject matter as, for example, in the literary parody and the mock-heroic. One of the most commonly cited examples of high burlesque is Alexander Pope’s “sly, knowing and courtly” The Rape of the Lock. [12] Low burlesque applied an irreverent, mocking style to a serious subject; an example is Samuel Butler’s poem Hudibras, which described the misadventures of a Puritan knight in satiric doggerel verse, using a colloquial idiom. Butler’s addition to his comic poem of an ethical subtext made his caricatures into satire. [13] In more recent times, burlesque true to its literary origins is still performed in revues and sketches. [8] Tom Stoppard’s 1974 play Travesties is an example of a full-length play drawing on the burlesque tradition. [14] Burlesque in music[edit] See also: Parody music Classical music[edit] Beginning in the early 18th century, the term burlesque was used throughout Europe to describe musical works in which serious and comic elements were juxtaposed or combined to achieve a grotesque effect. [15] As derived from literature and theatre, “burlesque” was used, and is still used, in music to indicate a bright or high-spirited mood, sometimes in contrast to seriousness. [15] In this sense of farce and exaggeration rather than parody, it appears frequently on the German-language stage between the middle of the 19th century and the 1920s. Burlesque operettas were written by Johann Strauss II (Die lustigen Weiber von Wien, 1868), [16] Ziehrer (Mahomed’s Paradies, 1866; Das Orakel zu Delfi, 1872; Cleopatra, oder Durch drei Jahrtausende, 1875; In fünfzig Jahren, 1911)[17] and Bruno Granichstaedten (Casimirs Himmelfahrt, 1911). French references to burlesque are less common than German, though Grétry composed for a “drame burlesque” (Matroco, 1777). [18] Stravinsky called his 1916 one-act chamber opera-ballet Renard (The Fox) a “Histoire burlesque chantée et jouée” (burlesque tale sung and played). A later example is the 1927 burlesque operetta by Ernst Krenek entitled Schwergewicht (Heavyweight) (1927). Burleske (1885-86), by Richard Strauss. Performed by Neal O’Doan with the Seattle Philharmonic Orchestra. Problems playing this file? Some orchestral and chamber works have also been designated as burlesques, of which two early examples are the Ouverture-Suite Burlesque de Quixotte, TWV 55, by Telemann and the Sinfonia Burlesca by Leopold Mozart (1760). Another often-performed piece is Richard Strauss’s 1890 Burleske for piano and orchestra. [15] Other examples include the following: 1901: Six Burlesques, Op. 58 for piano four hands by Max Reger 1904: Scherzo Burlesque, Op. 2 for piano and orchestra by Béla Bartók 1911: Three Burlesques, Op. 8c for piano by Bartók 1920: Burlesque for Piano, by Arnold Bax 1931: Ronde burlesque, Op. 78 for orchestra by Florent Schmitt 1932: Fantaisie burlesque, for piano by Olivier Messiaen 1956: Burlesque for Piano and Chamber Orchestra, Op. 13g by Bertold Hummel 1982: Burlesque for Wind Quintet, Op. 76b by Hummel Burlesque can be used to describe particular movements of instrumental musical compositions, often involving dance rhythms. Examples are the Burlesca, in Partita No. 3 for keyboard (BWV 827) by Bach, the “Rondo-Burleske” third movement of Symphony No. 9 by Mahler, and the “Burlesque” fourth movement of Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. [19] Jazz[edit] The use of burlesque has not been confined to classical music. Well known ragtime travesties include The Russian Rag, by George L. Cobb, which is based on Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp minor, and Harry Alford’s Lucy’s Sextette based on the sextet,’Chi mi frena in tal momento? , from Lucia di Lammermoor by Donizetti. [20] Victorian theatrical burlesque[edit]. John in Carmen up to Data Main article: Victorian burlesque Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as “travesty” or “extravaganza”, [21] was popular in London theatres between the 1830s and the 1890s. It took the form of musical theatre parody in which a well-known opera, play or ballet was adapted into a broad comic play, usually a musical play, often risqué in style, mocking the theatrical and musical conventions and styles of the original work, and quoting or pastiching text or music from the original work. The comedy often stemmed from the incongruity and absurdity of the classical subjects, with realistic historical dress and settings, being juxtaposed with the modern activities portrayed by the actors. Madame Vestris produced burlesques at the Olympic Theatre beginning in 1831 with Olympic Revels by J. [22] Other authors of burlesques included H. Gilbert and Fred Leslie. [23] Victorian burlesque related to and in part derived from traditional English pantomime with the addition of gags and’turns’. [24] In the early burlesques, following the example of ballad opera, the words of the songs were written to popular music;[25] later burlesques mixed the music of opera, operetta, music hall and revue, and some of the more ambitious shows had original music composed for them. This English style of burlesque was successfully introduced to New York in the 1840s. Sheet music from Faust up to Date Some of the most frequent subjects for burlesque were the plays of Shakespeare and grand opera. [27][28] The dialogue was generally written in rhyming couplets, liberally peppered with bad puns. [24] A typical example from a burlesque of Macbeth: Macbeth and Banquo enter under an umbrella, and the witches greet them with Hail! ” Macbeth asks Banquo, “What mean these salutations, noble thane? ” and is told, “These showers of’Hail’ anticipate your’reign’. [28] A staple of burlesque was the display of attractive women in travesty roles, dressed in tights to show off their legs, but the plays themselves were seldom more than modestly risqué. Programme: Ruy Blas and the Blasé Roué Burlesque became the speciality of certain London theatres, including the Gaiety and Royal Strand Theatre from the 1860s to the early 1890s. Until the 1870s, burlesques were often one-act pieces running less than an hour and using pastiches and parodies of popular songs, opera arias and other music that the audience would readily recognize. The house stars included Nellie Farren, John D’Auban, Edward Terry and Fred Leslie. [23][29] From about 1880, Victorian burlesques grew longer, until they were a whole evening’s entertainment rather than part of a double- or triple-bill. [23] In the early 1890s, these burlesques went out of fashion in London, and the focus of the Gaiety and other burlesque theatres changed to the new more wholesome but less literary genre of Edwardian musical comedy. [30] American burlesque[edit]. Advertisement for a burlesque troupe, 1898 Main article: American burlesque American burlesque shows were originally an offshoot of Victorian burlesque. The English genre had been successfully staged in New York from the 1840s, and it was popularised by a visiting British burlesque troupe, Lydia Thompson and the “British Blondes”, beginning in 1868. [31] New York burlesque shows soon incorporated elements and the structure of the popular minstrel shows. They consisted of three parts: first, songs and ribald comic sketches by low comedians; second, assorted olios and male acts, such as acrobats, magicians and solo singers; and third, chorus numbers and sometimes a burlesque in the English style on politics or a current play. The entertainment was usually concluded by an exotic dancer or a wrestling or boxing match. [32] While burlesque went out of fashion in England towards the end of the 19th century, to be replaced by Edwardian musical comedy, the American style of burlesque flourished, but with increasing focus on female nudity. Exotic “cooch” dances were brought in, ostensibly Syrian in origin. The entertainments were given in clubs and cabarets, as well as music halls and theatres. By the early 20th century, there were two national circuits of burlesque shows competing with the vaudeville circuit, as well as resident companies in New York, such as Minsky’s at the Winter Garden. Gypsy Rose Lee The transition from burlesque on the old lines to striptease was gradual. At first, soubrettes showed off their figures while singing and dancing; some were less active but compensated by appearing in elaborate stage costumes. [33] The strippers gradually supplanted the singing and dancing soubrettes; by 1932 there were at least 150 strip principals in the US. [33] Star strippers included Sally Rand, Gypsy Rose Lee, Tempest Storm, Lili St. Cyr, Blaze Starr, Ann Corio and Margie Hart, who was celebrated enough to be mentioned in song lyrics by Lorenz Hart and Cole Porter. [33] By the late 1930s, burlesque shows would have up to six strippers supported by one or two comics and a master of ceremonies. Comics who appeared in burlesque early in their careers included Fanny Brice, Mae West, Eddie Cantor, Abbott and Costello, W. Fields, Jackie Gleason, Danny Thomas, Al Jolson, Bert Lahr, Phil Silvers, Sid Caesar, Danny Kaye, Red Skelton and Sophie Tucker. Michelle L’amour, 2005 Miss Exotic World The uninhibited atmosphere of burlesque establishments owed much to the free flow of alcoholic liquor, and the enforcement of Prohibition was a serious blow. [34] In New York, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia clamped down on burlesque, effectively putting it out of business by the early 1940s. [35] It lingered on elsewhere in the U. Increasingly neglected, and by the 1970s, with nudity commonplace in theatres, reached its final shabby demise. [36] Both during its declining years and afterwards there have been films that sought to capture American burlesque, including Lady of Burlesque (1943), [37] Striporama (1953), [38] and The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968). [39] In recent decades, there has been a revival of burlesque, sometimes called Neo-Burlesque, [35] on both sides of the Atlantic. [40] A new generation, nostalgic for the spectacle and perceived glamour of the classic American burlesque, developed a cult following for the art in the early 1990s at Billie Madley’s “Cinema” and later at the “Dutch Weismann’s Follies” revues in New York City, “The Velvet Hammer” troupe in Los Angeles and The Shim-Shamettes in New Orleans. Ivan Kane’s Royal Jelly Burlesque Nightclub at Revel Atlantic City opened in 2012. [41] Notable Neo-burlesque performers include Dita Von Teese, and Julie Atlas Muz and Agitprop groups like Cabaret Red Light incorporated political satire and performance art into their burlesque shows. Annual conventions such as the Vancouver International Burlesque Festival and the Miss Exotic World Pageant are held. A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. Burlesque overlaps in meaning with caricature, parody and travesty, and, in its theatrical sense, with extravaganza, as presented during the Victorian era. [4] “Burlesque” has been used in English in this literary and theatrical sense since the late 17th century. [5] Contrasting examples of literary burlesque are Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock and Samuel Butler’s Hudibras. Literary origins and development. Arabella Fermor, target of The Rape of the Lock. The word first appears in a title in Francesco Berni’s Opere burlesche of the early 16th century, works that had circulated widely in manuscript before they were printed. [8] Shakespeare’s Pyramus and Thisbe scene in Midsummer Night’s Dream and the general mocking of romance in Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle were early examples of such imitation. In 17th century Spain, playwright and poet Miguel de Cervantes ridiculed medieval romance in his many satirical works. [10] The term burlesque has been applied retrospectively to works of Chaucer and Shakespeare and to the Graeco-Roman classics. Burlesque was intentionally ridiculous in that it imitated several styles and combined imitations of certain authors and artists with absurd descriptions. [11] Burlesque depended on the reader’s (or listener’s) knowledge of the subject to make its intended effect, and a high degree of literacy was taken for granted. 17th and 18th century burlesque was divided into two types: High burlesque refers to a burlesque imitation where a literary, elevated manner was applied to a commonplace or comically inappropriate subject matter as, for example, in the literary parody and the mock-heroic. [13] Low burlesque applied an irreverent, mocking style to a serious subject; an example is Samuel Butler’s poem Hudibras, which described the misadventures of a Puritan knight in satiric doggerel verse, using a colloquial idiom. In more recent times, burlesque true to its literary origins is still performed in revues and sketches. [9] Tom Stoppard’s 1974 play Travesties is an example of a full-length play drawing on the burlesque tradition. See also: Parody music. Beginning in the early 18th century, the term burlesque was used throughout Europe to describe musical works in which serious and comic elements were juxtaposed or combined to achieve a grotesque effect. [16] As derived from literature and theatre, “burlesque” was used, and is still used, in music to indicate a bright or high-spirited mood, sometimes in contrast to seriousness. In this sense of farce and exaggeration rather than parody, it appears frequently on the German-language stage between the middle of the 19th century and the 1920s. Burlesque operettas were written by Johann Strauss II (Die lustigen Weiber von Wien, 1868), [17] Ziehrer (Mahomed’s Paradies, 1866; Das Orakel zu Delfi, 1872; Cleopatra, oder Durch drei Jahrtausende, 1875; In fünfzig Jahren, 1911)[18] and Bruno Granichstaedten (Casimirs Himmelfahrt, 1911). [19] Stravinsky called his 1916 one-act chamber opera-ballet Renard (The Fox) a “Histoire burlesque chantée et jouée” (burlesque tale sung and played) and his 1911 ballet Petrushka a “burlesque in four scenes”. [16] Other examples include the following. 1901: Six Burlesques, Op. 58 for piano four hands by Max Reger. 1904: Scherzo Burlesque, Op. 2 for piano and orchestra by Béla Bartók. 1911: Three Burlesques, Op. 8c for piano by Bartók. 1920: Burlesque for Piano, by Arnold Bax. 1931: Ronde burlesque, Op. 78 for orchestra by Florent Schmitt. 1932: Fantaisie burlesque, for piano by Olivier Messiaen. 1956: Burlesque for Piano and Chamber Orchestra, Op. 13g by Bertold Hummel. 1982: Burlesque for Wind Quintet, Op. Burlesque can be used to describe particular movements of instrumental musical compositions, often involving dance rhythms. The use of burlesque has not been confined to classical music. John in Carmen up to Data. Main article: Victorian burlesque. Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as “travesty” or “extravaganza”, [22] was popular in London theatres between the 1830s and the 1890s. [23] Other authors of burlesques included H. Victorian burlesque related to and in part derived from traditional English pantomime with the addition of gags and’turns’. [25] In the early burlesques, following the example of ballad opera, the words of the songs were written to popular music;[26] later burlesques mixed the music of opera, operetta, music hall and revue, and some of the more ambitious shows had original music composed for them. Sheet music from Faust up to Date. Some of the most frequent subjects for burlesque were the plays of Shakespeare and grand opera. [28][29] The dialogue was generally written in rhyming couplets, liberally peppered with bad puns. [25] A typical example from a burlesque of Macbeth: Macbeth and Banquo enter under an umbrella, and the witches greet them with Hail! [29] A staple of burlesque was the display of attractive women in travesty roles, dressed in tights to show off their legs, but the plays themselves were seldom more than modestly risqué. Programme: Ruy Blas and the Blasé Roué. Burlesque became the speciality of certain London theatres, including the Gaiety and Royal Strand Theatre from the 1860s to the early 1890s. [24][30] From about 1880, Victorian burlesques grew longer, until they were a whole evening’s entertainment rather than part of a double- or triple-bill. [24] In the early 1890s, these burlesques went out of fashion in London, and the focus of the Gaiety and other burlesque theatres changed to the new more wholesome but less literary genre of Edwardian musical comedy. Advertisement for a burlesque troupe, 1898. Main article: American burlesque. American burlesque shows were originally an offshoot of Victorian burlesque. [32] New York burlesque shows soon incorporated elements and the structure of the popular minstrel shows. While burlesque went out of fashion in England towards the end of the 19th century, to be replaced by Edwardian musical comedy, the American style of burlesque flourished, but with increasing focus on female nudity. The transition from burlesque on the old lines to striptease was gradual. [34] The strippers gradually supplanted the singing and dancing soubrettes; by 1932 there were at least 150 strip principals in the US. [34] Star strippers included Sally Rand, Gypsy Rose Lee, Tempest Storm, Lili St. [34] By the late 1930s, burlesque shows would have up to six strippers supported by one or two comics and a master of ceremonies. Michelle L’amour, 2005 Miss Exotic World. The uninhibited atmosphere of burlesque establishments owed much to the free flow of alcoholic liquor, and the enforcement of Prohibition was a serious blow. [35] In New York, Mayor Fiorello H. [36] It lingered on elsewhere in the U. [37] Both during its declining years and afterwards there have been films that sought to capture American burlesque, including Lady of Burlesque (1943), [38] Striporama (1953), [39] and The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968). The “Stage Door Johnnies” performing at the Burlesque Hall of Fame in Las Vegas, 2011. In recent decades, there has been a revival of burlesque, sometimes called Neo-Burlesque, [36] on both sides of the Atlantic. [41] A new generation, nostalgic for the spectacle and perceived glamour of the classic American burlesque, developed a cult following for the art in the early 1990s at Billie Madley’s “Cinema” and later at the “Dutch Weismann’s Follies” revues in New York City, “The Velvet Hammer” troupe in Los Angeles and The Shim-Shamettes in New Orleans. [42] Notable Neo-burlesque performers include Dita Von Teese, and Julie Atlas Muz and Agitprop groups like Cabaret Red Light incorporated political satire and performance art into their burlesque shows. Cabaret is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub[1] with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining or drinking, does not typically dance but usually sits at tables. Performances are usually introduced by a master of ceremonies or MC. The entertainment, as done by an ensemble of actors and according to its European origins, is often (but not always) oriented towards adult audiences and of a clearly underground nature. In the United States, striptease, burlesque, drag shows, or a solo vocalist with a pianist, as well as the venues which offer this entertainment, are often advertised as cabarets. The term originally came from Picard language or Walloon language words camberete or cambret for a small room (12th century). The first printed use of the word kaberet is found in a document from 1275 in Tournai. The term was used since the 13th century in Middle Dutch to mean an inexpensive inn or restaurant (caberet, cabret). The word cambret, itself probably derived from an earlier form of chambrette, little room, or from the Norman French chamber meaning tavern, itself derived from the Late Latin word camera meaning an arched roof. Cabarets had appeared in Paris by at least the late 15th century. They were distinguished from taverns because they served food as well as wine, the table was covered with a cloth, and the price was charged by the plate, not the mug. [4] They were not particularly associated with entertainment even if musicians sometimes performed in both. [5] Early on, cabarets were considered better than taverns; by the end of the sixteenth century, they were the preferred place to dine out. Cabarets were frequently used as meeting places for writers, actors, friends and artists. Writers such as La Fontaine, Moliere and Jean Racine were known to frequent a cabaret called the Mouton Blanc on rue du Vieux-Colombier, and later the Croix de Lorraine on the modern rue Bourg-Tibourg. In 1773, French poets, painters, musicians and writers began to meet in a cabaret called Le Caveau on rue de Buci, where they composed and sang songs. The Caveau continued until 1816, when it was forced to close because its clients wrote songs mocking the royal government. The Café des Aveugles in the cellars of the Palais-Royal (beginning of the 19th century). In the 18th century, the café-concert or café-chantant appeared, which offered food along with music, singers, or magicians. The most famous was the Cafe des Aveugles in the cellars of the Palais-Royal, which had a small orchestra of blind musicians. In the early 19th century, many cafés-chantants appeared around the city; the most famous were the Café des Ambassadeurs (1843) on the Champs-Élysées and the Eldorado (1858) on boulevard Strasbourg. By 1900, there were more than 150 cafés-chantants in Paris. The first cabaret in the modern sense was Le Chat Noir in the bohemian neighborhood of Montmartre, created in 1881 by Rodolphe Salis, a theatrical agent and entrepreneur. [7] It combined music and other entertainment with political commentary and satire. [8] The Chat Noir brought together the wealthy and famous of Paris with the bohemians and artists of Montmartre and the Pigalle. Its clientele was a mixture of writers and painters, of journalists and students, of employees and high-livers, as well as models, prostitutes and true grand dames searching for exotic experiences. [9] The host was Salis himself, calling himself a gentleman-cabaretier; he began each show with a monologue mocking the wealthy, ridiculing the deputies of the National Assembly, and making jokes about the events of the day. The cabaret was too small for the crowds trying to get in; at midnight on June 10, 1885, Salis and his customers moved down the street to a larger new club at 12 rue de Laval, which had a decor described as A sort of Beirut with Chinese influences. The composer Eric Satie, after finishing his studies at the Conservatory, earned his living playing the piano at the Chat Noir. The composer Eric Satie playing the piano at Le Chat Noir (1880s). By 1896, there were 56 cabarets and cafes with music in Paris, along with a dozen music halls. The cabarets did not have a high reputation; one critic wrote in 1897 that they sell drinks which are worth fifteen centimes along with verses which, for the most part, are worth nothing. [9] The traditional cabarets, with monologues and songs and little decor, were replaced by more specialized venues; some, like the Boite a Fursy (1899), specialized in current events, politics and satire. Some were purely theatrical, producing short scenes of plays. Some focused on the macabre or erotic. The Caberet de la fin du Monde had servers dressed as Greek and Roman gods and presented living tableaus that were between erotic and pornographic. By the end of the century, there were only a few cabarets of the old style remaining where artists and bohemians gathered. They included the Cabaret des noctambules on Rue Champollion on the Left Bank; the Lapin Agile at Montmartre; and Le Soleil d’or at the corner of the quai Saint-Michel and boulevard Saint-Michel, where poets including Guillaume Apollinaire and André Salmon met to share their work. The music hall, first invented in London, appeared in Paris in 1862. It offered more lavish musical and theatrical productions, with elaborate costumes, singing, and dancing. The theaters of Paris, fearing competition from the music halls, had a law passed by the National Assembly forbidding music hall performers to wear costumes, dance, wear wigs, or recite dialogue. The law was challenged by the owner of the music hall Eldorado in 1867, who put a former famous actress from the Comédie-Française on stage to recite verse from Corneille and Racine. The public took the side of the music halls, and the law was repealed. The Moulin Rouge in 1893. 1896 advertisement for a tour of the first French cabaret show, Le Chat Noir. The Moulin Rouge was opened in 1889 by the Catalan Joseph Oller. It was greatly prominent because of the large red imitation windmill on its roof, and became the birthplace of the dance known as the French Cancan. It helped make famous the singers Mistinguett and Édith Piaf and the painter Toulouse-Lautrec, who made posters for the venue. The Olympia, also run by Oller, was the first to be called a music hall; it opened in 1893, followed by the Alhambra Music Hall in 1902, and the Printania in 1903. The Printania, open only in summer, had a large music garden which seated twelve thousand spectators, and produced dinner shows which presented twenty-three different acts, including singers, acrobats, horses, mimes, jugglers, lions, bears and elephants, with two shows a day. In the 20th century, the competition from motion pictures forced the dance halls to put on shows that were more spectacular and more complex. In 1911, the producer Jacques Charles of the Olympia Paris created the grand staircase as a setting for his shows, competing with its great rival, the Folies Bergère which had been founded in 1869. Its stars in the 1920s included the American singer and dancer Josephine Baker. The Casino de Paris, directed by Leon Volterra and then Henri Varna, presented many famous French singers, including Mistinguett, Maurice Chevalier, and Tino Rossi. Le Lido on the Champs-Élysées opened in 1946, presenting Édith Piaf, Laurel and Hardy, Shirley MacLaine, Marlene Dietrich, Maurice Chevalier, and Noël Coward. The Crazy Horse Saloon, featuring striptease, dance, and magic, opened in 1951. The Olympia Paris went through a number of years as a movie theater before being revived as a music hall and concert stage in 1954. Performers there included Piaf, Dietrich, Miles Davis, Judy Garland, and the Grateful Dead. A handful of music halls exist today in Paris, attended mostly by visitors to the city; and a number of more traditional cabarets, with music and satire, can be found. In the Netherlands, cabaret or kleinkunst (literally: “small art”) is a popular form of entertainment, usually performed in theatres. The birth date of Dutch cabaret is usually set at August 19, 1895. [12] In Amsterdam, there is the Kleinkunstacademie (English: Cabaret Academy). It is often a mixture of (stand-up) comedy, theatre, and music and often includes social themes and political satire. In the mid twentieth century, “the big three” were Wim Sonneveld, Wim Kan, and Toon Hermans. Nowadays, many cabaret shows of popular “cabaretiers” (performers of cabaret) are broadcast on national television, especially on New Year’s Eve, when several special cabaret shows are aired where the cabaretier usually reflects on large events of the past year. German Kabarett developed from 1901, with the creation of the Überbrettl (Superstage) venue, and by the Weimar era in the mid-1920s, the Kabarett performances were characterized by political satire and gallows humor. [14] It shared the characteristic atmosphere of intimacy with the French cabaret from which it was imported, but the gallows humor was a distinct German aspect. See also: Category:Polish cabarets. The Polish kabaret is a popular form of live (often televised) entertainment involving a comedy troupe, and consisting mostly of comedy sketches, monologues, stand up comedy, songs and political satire (often hidden behind double entendre to fool censors). It traces its origins to Zielony Balonik, a famous literary cabaret founded in Kraków by local poets, writers and artists during the final years of the Partitions of Poland. In the interwar Poland there was a considerable number of Yiddish-language cabarets. This art form was called kleynkunst (lliterally “small art”) in Yiddish. In post-war Poland, it is almost always associated with the troupe (often on tour), not the venue; pre-war revue shows (with female dancers) were long gone. A long-established cabaret venue in Manhattan, New York. American cabaret was imported from French cabaret by Jesse Louis Lasky in 1911. [17][18][19] In the United States, cabaret diverged into several different styles of performance mostly due to the influence of jazz music. Chicago cabaret focused intensely on the larger band ensembles and reached its peak during Roaring Twenties, under the Prohibition Era, where it was featured in the speakeasies and steakhouses. New York cabaret never developed to feature a great deal of social commentary. When New York cabarets featured jazz, they tended to focus on famous vocalists like Nina Simone, Bette Midler, Eartha Kitt, Peggy Lee, and Hildegarde rather than instrumental musicians. Julius Monk’s annual revues established the standard for New York cabaret during the late 1950s and’60s. Cabaret in the United States began to decline in the 1960s, due to the rising popularity of rock concert shows, television variety shows, [citation needed] and general comedy theaters. However, it remained in some Las Vegas-style dinner shows, such as the Tropicana, with fewer comedy segments. The art form still survives in various musical formats, as well as in the stand-up comedy format, and in popular drag show performances. The late 20th and early 21st century saw a revival of American cabaret, particularly in New Orleans, Chicago, Seattle, Portland, Philadelphia, Orlando, Tulsa, Asheville, North Carolina, and Kansas City, Missouri, as new generations of performers reinterpret the old forms in both music and theater. Many contemporary cabaret groups in the United States and elsewhere feature a combination of original music, burlesque and political satire. In New York City, since 1985, successful, enduring or innovative cabaret acts have been honored by the annual Bistro Awards. The Ani Mru Mru Polish cabaret group performing in Edinburgh in 2007. The Cabaret Theatre Club, later known as The Cave of the Golden Calf, was opened by Frida Strindberg (modelled on the Kaberett Fledermaus in Strindberg’s native Vienna) in a basement at 9 Heddon Street, London, in 1912. She intended her club to be an avant-garde meeting place for bohemian writers and artists, with decorations by Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, and Wyndham Lewis, but it rapidly came to be seen as an amusing place for high society and went bankrupt in 1914. The Cave was nevertheless an influential venture, which introduced the concept of cabaret to London. It provided a model for the generation of nightclubs that came after it. The clubs that started the present vogue for dance clubs were the Cabaret Club in Heddon Street. The Cabaret Club was the first club where members were expected to appear in evening clothes. The Cabaret Club began a system of vouchers which friends of members could use to obtain admission to the club. The question of the legality of these vouchers led to a famous visitation of the police. That was the night a certain Duke was got out by way of the kitchen lift. The visitation was a well-mannered affair'[22]. Saint Bongita in the 1974 Christmas show at the Poor House, Stockholm. In Stockholm, an underground show called Fattighuskabarén (Poor House Cabaret) opened in 1974 and ran for 10 years. [23] Performers of later celebrity and fame (in Sweden) such as Ted Åström, Örjan Ramberg, and Agneta Lindén began their careers there. Wild Side Story also had several runs in Stockholm, at Alexandra’s (1976 with Ulla Jones and Christer Lindarw), [24][25][26] Camarillo (1997), [27][28] Rosenlundsteatern/Teater Tre (2000), [29] Wild Side Lounge at Bäckahästen (2003 with Helena Mattsson)[30] and Mango Bar (2004). [31] Alexandra’s had also hosted AlexCab in 1975, [32] as had Compagniet in Gothenburg. In 2019 the first Serbian cabaret club Lafayette opened. [34] Although Serbia and Belgrade had a rich night and theater life there was no cabaret house until 2019. Cabane Choucoune in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Cabaret Red Light in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich. Café Carlyle in New York City. Café de Paris in London, England. The Cabaret in Indianapolis, Indiana. Cabaret rooms at various Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatres. Crazy Horse in Paris, France. Darling Cabaret in Prague. El Mocambo in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. El Molino [es] in Barcelona, Spain. Feinstein’s/54 Below in New York City. Folies Bergere in Paris, France. Lapin Agile in Paris, France. Le Lido in Paris, France. Metro Chicago in Chicago, Illinois. Moulin Rouge in Paris, France. The Tropicana in Havana, Cuba. Lafayette in Belgrade, Serbia. Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. [1] Perceptions of a distinction in Britain between bold and scandalous Victorian Music Hall and subsequent, more respectable Variety differ. Music hall involved a mixture of popular songs, comedy, speciality acts, and variety entertainment. [2] The term is derived from a type of theatre or venue in which such entertainment took place. In North America vaudeville was in some ways analogous to British music hall, [3] featuring rousing songs and comic acts. Originating in saloon bars within public houses during the 1830s, music hall entertainment became increasingly popular with audiences. So much so, that during the 1850s some public houses were demolished, and specialised music hall theatres developed in their place. These theatres were designed chiefly so that people could consume food and alcohol and smoke tobacco in the auditorium while the entertainment took place. This differed from the conventional type of theatre, which seats the audience in stalls with a separate bar-room. [4] Major music halls were based around London. Early examples included: the Canterbury Music Hall in Lambeth, Wilton’s Music Hall in Tower Hamlets, and The Middlesex in Drury Lane, otherwise known as the Old Mo. By the mid-19th century, the halls cried out for many new and catchy songs. As a result, professional songwriters were enlisted to provide the music for a plethora of star performers, such as Marie Lloyd, Dan Leno, Little Tich, and George Leybourne. All manner of other entertainment was performed: male and female impersonators, lions comiques, mime artists and impressionists, trampoline acts, and comic pianists (such as John Orlando Parry and George Grossmith) were just a few of the many types of entertainments the audiences could expect to find over the next forty years. The Music Hall Strike of 1907 was an important industrial conflict. It was a dispute between artists and stage hands on one hand, and theatre managers on the other, culminating in a strike. [6] The halls had recovered by the start of the First World War and were used to stage charity events in aid of the war effort. Music hall entertainment continued after the war, but became less popular due to upcoming jazz, swing, and big-band dance music acts. Licensing restrictions had also changed, and drinking was banned from the auditorium. A new type of music hall entertainment had arrived, in the form of variety, and many music hall performers failed to make the transition. They were deemed old-fashioned, and with the closure of many halls, music hall entertainment ceased and modern-day variety began. Music Hall War’ of 1907. Music halls of Paris. History of the songs. Famous music hall songs. Cultural influences of music hall: Literature, drama, screen, and later music. Music-halls had their origins in 18th century London. [8] It grew with the entertainment provided in the new style saloon bars of public houses during the 1830s. These venues replaced earlier semi-rural amusements provided by fairs and suburban pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall Gardens and the Cremorne Gardens. These latter became subject to urban development and became fewer and less popular. The most famous London saloon of the early days was the Grecian Saloon, established in 1825, at The Eagle (a former tea-garden), 2 Shepherdess Walk, off the City Road in east London. [10] According to John Hollingshead, proprietor of the Gaiety Theatre, London (originally the Strand Music Hall), this establishment was “the father and mother, the dry and wet nurse of the Music Hall”. Later known as the Grecian Theatre, it was here that Marie Lloyd made her début at the age of 14 in 1884. It is still famous because of an English nursery rhyme, with the somewhat mysterious lyrics. Up and down the City Road. In and out The Eagle. Pop goes the weasel. The interior of Wilton’s Music Hall (here, being set for a wedding). The line of tables give some idea of how early music halls were used as supper clubs. Another famous “song and supper” room of this period was Evans Music-and-Supper Rooms, 43 King Street, Covent Garden, established in the 1840s by W. This venue was also known as’Evans Late Joys’ – Joy being the name of the previous owner. Other song and supper rooms included the Coal Hole in The Strand, the Cyder Cellars in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden and the Mogul Saloon in Drury Lane. The music hall as we know it developed from such establishments during the 1850s and were built in and on the grounds of public houses. Such establishments were distinguished from theatres by the fact that in a music hall you would be seated at a table in the auditorium and could drink alcohol and smoke tobacco whilst watching the show. In a theatre, by contrast, the audience was seated in stalls and there was a separate bar-room. An exception to this rule was the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton (1841) which somehow managed to evade this regulation and served drinks to its customers. Though a theatre rather than a music hall, this establishment later hosted music hall variety acts. Interior of the Canterbury Hall, opened 1852 in Lambeth. The establishment often regarded as the first true music hall was the Canterbury, 143 Westminster Bridge Road, Lambeth built by Charles Morton, afterwards dubbed “the Father of the Halls”, on the site of a skittle alley next to his pub, the Canterbury Tavern. It opened on 17 May 1852 and was described by the musician and author Benny Green as being “the most significant date in all the history of music hall”. [13] The hall looked like most contemporary pub concert rooms, but its replacement in 1854 was of then unprecedented size. It was further extended in 1859, later rebuilt as a variety theatre and finally destroyed by German bombing in 1942. Another early music hall was The Middlesex, Drury Lane (1851). Popularly known as the’Old Mo’, it was built on the site of the Mogul Saloon. Later converted into a theatre it was demolished in 1965. The New London Theatre stands on its site. Several large music halls were built in the East End. This theatre was rebuilt during 1894 by Frank Matcham, the architect of the Hackney Empire. Designed by William Finch Hill (the designer of the Britannia theatre in nearby Hoxton), it was rebuilt after a fire in 1898. Balcony at the Alhambra by Spencer Gore; 1910-11. The construction of Weston’s Music Hall, High Holborn (1857), built up on the site of the Six Cans and Punch Bowl Tavern by the licensed victualler of the premises, Henry Weston, signalled that the West End was fruitful territory for the music hall. During 1906 it was rebuilt as a variety theatre and renamed as the Holborn Empire. It was closed as a result of German action in the Blitz on the night of 11-12 May 1941 and the building was pulled down in 1960. [18] Significant West End music halls include. The Oxford Music Hall, 14/16 Oxford Street (1861) – built on the site of an old coaching inn called the Boar and Castle by Charles Morton, the pioneer music hall developer of The Canterbury, who with this development brought music hall to the West End. The London Pavilion (1861). Facade of 1885 rebuild still extant. The Alhambra Theatre of Variety (1860) in London, which became a model for Parisian music halls. Some years before the Folies-Bergere it staged circus attractions alongside popular ballets in 55 new productions between 1864 and 1870. Little Dot Hetherington at the Old Bedford by Walter Sickert; c. Other large suburban music halls included. The Bedford, 93-95 High Street, Camden Town, constructed on the site of the tea gardens of a pub called the Bedford Arms. The first building, the Bedford Music Hall (“The Old Bedford”), opened in 1861 and closed in 1898. It was demolished and rebuilt as the larger Bedford Palace of Varieties also known as the Bedford Theatre (“The New Bedford”), which opened in 1899 and operated until 1959. The Bedford was a favourite haunt of the artist Walter Sickert, who featured interior scenes of music halls in many of his paintings, including one entitled’Little Dot Hetherington at The Old Bedford’. The Bedford was derelict from 1959 and finally demolished in 1969. Collins’, Islington Green (1862). Opened by Sam Collins, in 1862, as the Lansdowne Music Hall, converting the pre-existing Lansdowne Arms public house, it was renamed as Collins’ Music Hall in 1863. It was colloquially known as’The Chapel on the Green’. Collins was a star of his own theatre, singing mostly Irish songs specially composed for him. It closed in 1956, after a fire, but the street front of the building still survives (see below). Deacons in Clerkenwell (1862). A noted music hall entrepreneur of this time was Carlo Gatti who built a music hall, known as Gatti’s, at Hungerford Market in 1857. He converted the restaurant into a second Gatti’s music hall, known as “Gatti’s-in-the-Road”, in 1865. It later became a cinema. The building was badly damaged in the Second World War, and was demolished in 1950. In 1867, he acquired a public house in Villiers Street named “The Arches”, under the arches of the elevated railway line leading to Charing Cross station. He opened it as another music hall, known as “Gatti’s-in-The-Arches”. After his death his family continued to operate the music hall, known for a period as the Hungerford or Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties. It became a cinema in 1910, and the Players’ Theatre in 1946. By 1865, there were 32 music halls in London seating between 500 and 5,000 people plus an unknown, but large, number of smaller venues. In 1878, numbers peaked, with 78 large music halls in the metropolis and 300 smaller venues. Thereafter numbers declined due to stricter licensing restrictions imposed by the Metropolitan Board of Works and London County Council, and because of commercial competition between popular large suburban halls and the smaller venues, which put the latter out of business. A few of the UK’s music halls have survived and have retained many of their original features. Amongst the best examples in the United Kingdom are. Victoria Hall, Settle is a Grade II listed concert hall in Kirkgate, Settle, North Yorkshire, England. It is the UK’s oldest surviving music hall having opened as Settle Music Hall on 11 October 1853. The Music Hall was renamed’The Victoria Hall’ around November 1892. Wilton’s Music Hall is a Grade II listed building in Shadwell, built by John Wilton in 1859 as a music hall and now run as a multi-arts performance space in Graces Alley, off Cable Street in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The Britannia Music Hall (later known as The Panopticon or The Britannia Panopticon) in Trongate, Glasgow, Scotland was built in 1857/58 and is located above an amusement arcade at 113-117 Trongate. A new era of variety theatre was developed by the rebuilding of the London Pavilion in 1885. Hitherto the halls had borne unmistakeable evidence of their origins, but the last vestiges of their old connections were now thrown aside, and they emerged in all the splendour of their new-born glory. The highest efforts of the architect, the designer and the decorator were enlisted in their service, and the gaudy and tawdry music hall of the past gave way to the resplendent “theatre of varieties” of the present day, with its classic exterior of marble and freestone, its lavishly appointed auditorium and its elegant and luxurious foyers and promenades brilliantly illuminated by myriad electric lights. Charles Stuart and A. Park The Variety Stage (1895). One of the most famous of these new palaces of pleasure in the West End was the Empire, Leicester Square, built as a theatre in 1884 but acquiring a music hall licence in 1887. Like the nearby Alhambra this theatre appealed to the men of leisure by featuring alluring ballet dancers and had a notorious promenade which was the resort of courtesans. Another spectacular example of the new variety theatre was the Tivoli in the Strand built 1888-90 in an eclectic neo-Romanesque style with Baroque and Moorish-Indian embellishments. “The Tivoli” became a brand name for music-halls all over the British Empire. [26] During 1892, the Royal English Opera House, which had been a financial failure in Shaftesbury Avenue, applied for a music hall licence and was converted by Walter Emden into a grand music hall and renamed the Palace Theatre of Varieties, managed by Charles Morton. [27] Denied by the newly created LCC permission to construct the promenade, which was such a popular feature of the Empire and Alhambra, the Palace compensated in the way of adult entertainment by featuring apparently nude women in tableaux vivants, though the concerned LCC hastened to reassure patrons that the girls who featured in these displays were actually wearing flesh-toned body stockings and were not naked at all. One of the grandest of these new halls was the Coliseum Theatre built by Oswald Stoll in 1904 at the bottom of St Martin’s Lane. [29] This was followed by the London Palladium (1910) in Little Argyll Street. Both were designed by the prolific Frank Matcham. [30] As music hall grew in popularity and respectability, and as the licensing authorities exercised ever firmer regulation, [31] the original arrangement of a large hall with tables at which drink was served, changed to that of a drink-free auditorium. The acceptance of music hall as a legitimate cultural form was established by the first Royal Variety Performance before King George V during 1912 at the Palace Theatre. However, consistent with this new respectability the best-known music hall entertainer of the time, Marie Lloyd, was not invited, being deemed too “saucy” for presentation to the monarchy. 1907 poster from the Music Hall War between artists and theatre managers. The development of syndicates controlling a number of theatres, such as the Stoll circuit, increased tensions between employees and employers. On 22 January 1907, a dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire worsened. Strikes in other London and suburban halls followed, organised by the Variety Artistes’ Federation. The strike lasted for almost two weeks and was known as the Music Hall War. [33] It became extremely well known, and was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen of the trade union and Labour movement – Ben Tillett and Keir Hardie for example. Picket lines were organized outside the theatres by the artistes, while in the provinces theatre management attempted to oblige artistes to sign a document promising never to join a trade union. The strike ended in arbitration, which satisfied most of the main demands, including a minimum wage and maximum working week for musicians. Several music hall entertainers such as Marie Dainton, Marie Lloyd, Arthur Roberts, Joe Elvin and Gus Elen were strong advocates of the strike, though they themselves earned enough not to be concerned personally in a material sense. [34] Lloyd explained her advocacy. We (the stars) can dictate our own terms. For this they have to do double turns, and now matinées have been added as well. These poor things have been compelled to submit to unfair terms of employment, and I mean to back up the federation in whatever steps are taken. Marie Lloyd, on the Music Hall War[35][36]. See also: Recruitment to the British Army during the First World War. May 1915 poster by E. Kealey, from the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee. World War I may have been the high-water mark of music hall popularity. The artists and composers threw themselves into rallying public support and enthusiasm for the war effort. Patriotic music hall compositions such as “Keep the Home Fires Burning” (1914), “Pack up Your Troubles” (1915), “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” (1914) and “We Don’t Want to Lose You (But We Think You Ought To Go)” (1914), were sung by music hall audiences, and sometimes by soldiers in the trenches. Many songs promoted recruitment (“All the boys in khaki get the nice girls”, 1915); others satirised particular elements of the war experience. “What did you do in the Great war, Daddy” (1919) criticised profiteers and slackers; Vesta Tilley’s “I’ve got a bit of a blighty one” (1916) showed a soldier delighted to have a wound just serious enough to be sent home. The rhymes give a sense of grim humour (“When they wipe my face with sponges / and they feed me on blancmanges / I’m glad I’ve got a bit of a blighty one”). Tilley became more popular than ever during this time, when she and her husband, Walter de Frece, managed a military recruitment drive. In the guise of characters like’Tommy in the Trench’ and’Jack Tar Home from Sea’, Tilley performed songs such as “The army of today’s all right” and “Jolly Good Luck to the Girl who Loves a Soldier”. This is how she got the nickname Britain’s best recruiting sergeant – young men were sometimes asked to join the army on stage during her show. Her husband was knighted in 1919 for his own services to the war effort, and Tilley became Lady de Frece. Once the reality of war began to sink home, the recruiting songs all but disappeared – the Greatest Hits collection for 1915 published by top music publisher Francis and Day contains no recruitment songs. After conscription was brought in 1916, songs dealing with the war spoke mostly of the desire to return home. Many also expressed anxiety about the new roles women were taking in society. Possibly the most notorious of music hall songs from the First World War was Oh! It’s a lovely war (1917), popularised by male impersonator Ella Shields. Music hall continued during the interwar period, no longer the single dominant form of popular entertainment in Britain. The improvement of cinema, the development of radio, and the cheapening of the gramophone damaged its popularity greatly. It now had to compete with jazz, swing and big band dance music. Licensing restrictions also changed its character. In 1914, the London County Council (LCC) enacted that drinking be banished from the auditorium into a separate bar and, during 1923, the separate bar was abolished by parliamentary decree. The exemption of the theatres from this latter act prompted some critics to denounce this legislation as an attempt to deprive the working classes of their pleasures, as a form of social control, whilst sparing the supposedly more responsible upper classes who patronised the theatres (though this could be due to the licensing restrictions brought about due to the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, which also applied to public houses). [40] Even so, the music hall gave rise to such major stars as George Formby, Gracie Fields, Max Miller, Will Hay, and Flanagan and Allen during this period. In the mid-1950s, rock and roll, whose performers initially topped music hall bills, attracted a young audience who had little interest in the music hall acts, while driving the older audience away. The final demise was competition from television, which grew popular after the Queen’s coronation was televised. Some music halls tried to retain an audience by putting on striptease acts. In 1957, the playwright John Osborne delivered this elegy:[41]. The music hall is dying, and with it, a significant part of England. Some of the heart of England has gone; something that once belonged to everyone, for this was truly a folk art. John Osborne, The Entertainer (1957). Moss Empires, the largest British music hall chain, closed the majority of its theatres in 1960, closely followed by the death of music hall stalwart Max Miller in 1963, prompting one contemporary to write that: Music-halls… Died this afternoon when they buried Max Miller. [42][43] Miller himself had sometimes said that the genre would die with him. Many music hall performers, unable to find work, fell into poverty; some did not even have a home, having spent their working lives living in digs between performances. Stage and film musicals, however, continued to be influenced by the music hall idiom, including Oliver! Dr Dolittle and My Fair Lady. The BBC series The Good Old Days, which ran for thirty years, recreated the music hall for the modern audience, and the Paul Daniels Magic Show allowed several speciality acts a television presence from 1979 to 1994. Aimed at a younger audience, but still owing a lot to the music hall heritage, was the late-1970s’ television series, The Muppet Show. The Café-Concert by Edgar Degas (1876-77). Mistinguett at the Moulin Rouge (1911). The music hall was first imported into France in its British form in 1862, but under the French law protecting the state theatres, performers could not wear costumes or recite dialogue, something only allowed in theaters. When the law changed in 1867, the Paris music hall flourished, and a half-dozen new halls opened, offering acrobats, singers, dancers, magicians, and trained animals. The first Paris music call built specially for that purpose was the Folies-Bergere (1869); it was followed by the Moulin Rouge (1889), the Alhambra (1866), the first to be called a music hall, and the Olympia (1893). The Printania (1903) was a music-garden, open only in summer, with a theater, restaurant, circus, and horse-racing. Older theaters also transformed themselves into music halls, including the Bobino (1873), the Bataclan (1864), and the Alcazar (1858). At the beginning, music halls offered dance reviews, theater and songs, but gradually songs and singers became the main attraction. Josephine Baker dances the Charleston at the Folies Bergère (1926). The Olympia Music Hall. Paris music halls all faced stiff competition in the interwar period from the most popular new form of entertainment, the cinema. They responded by offering more complex and lavish shows. In 1911, the Olympia had introduced the giant stairway as a set for its productions, an idea copied by other music halls. Gaby Deslys rose in popularity and created, with her dance partner Harry Pilcer, her most famous dance The Gaby Glide. [46] The singer Mistinguett made her debut the Casino de Paris in 1895, and continued to appear regularly in the 1920s and 1930s at the Folies Bergère, Moulin Rouge and Eldorado. Her risqué routines captivated Paris, and she became one of the most highly-paid and popular French entertainers of her time. One of the most popular entertainers in Paris during the period was the American singer Josephine Baker. Baker sailed to Paris, France. She first arrived in Paris in 1925 to perform in a show called La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. [48] She became an immediate success for her erotic dancing, and for appearing practically nude on stage. Baker performed the’Danse sauvage,’ wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas. The music-halls suffered growing hardships in the 1930s. The Olympia was converted into a movie theater, and others closed. Others however continued to thrive. In 1937 and 1930, the Casino de Paris presented shows with Maurice Chevalier, who had already achieved success as an actor and singer in Hollywood. In 1935, a twenty-year old singer named Édith Piaf was discovered in the Pigalle by nightclub owner Louis Leplée, whose club, Le Gerny, off the Champs-Élysées, was frequented by the upper and lower classes alike. He persuaded her to sing despite her extreme nervousness. Leplée ran an intense publicity campaign leading up to her opening night, attracting the presence of many celebrities, including Maurice Chevalier. Her nightclub appearance led to her first two records produced that same year, and the beginning of her career. Competition from movies and television largely brought an end to the Paris music hall. However, a few still flourish, with tourists as their primary audience. Major music halls include the Folies-Bergere, Crazy Horse Saloon, Casino de Paris, Olympia, and Moulin Rouge. The musical forms most associated with music hall evolved in part from traditional folk song and songs written for popular drama, becoming by the 1850s a distinct musical style. Subject matter became more contemporary and humorous, and accompaniment was provided by larger house-orchestras, as increasing affluence gave the lower classes more access to commercial entertainment, and to a wider range of musical instruments, including the piano. The consequent change in musical taste from traditional to more professional forms of entertainment, arose in response to the rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of previously rural populations during the Industrial Revolution. The newly created urban communities, cut off from their cultural roots, required new and readily accessible forms of entertainment. Music halls were originally tavern rooms which provided entertainment, in the form of music and speciality acts, for their patrons. By the middle years of the nineteenth century, the first purpose-built music halls were being built in London. The halls created a demand for new and catchy popular songs, that could no longer be met from the traditional folk song repertoire. Professional songwriters were enlisted to fill the gap. The emergence of a distinct music hall style can be credited to a fusion of musical influences. Music hall songs needed to gain and hold the attention of an often jaded and unruly urban audience. In America, from the 1840s, Stephen Foster had reinvigorated folk song with the admixture of Negro spiritual to produce a new type of popular song. Songs like “Old Folks at Home” (1851)[50] and “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” (James Bland, 1879)[51] spread round the globe, taking with them the idiom and appurtenances of the minstrel song. Other influences on the rapidly developing music hall idiom were Irish and European music, particularly the jig, polka, and waltz. Typically, a music hall song consists of a series of verses sung by the performer alone, and a repeated chorus which carries the principal melody, and in which the audience is encouraged to join. George Leybourne as’Champagne Charlie’. Artwork by Alfred Concanen. In Britain, the first music hall songs often promoted the alcoholic wares of the owners of the halls in which they were performed. Songs like “Glorious Beer”, [52] and the first major music hall success, “Champagne Charlie” (1867) had a major influence in establishing the new art form. The tune of “Champagne Charlie” became used for the Salvation Army hymn “Bless His Name, He Sets Me Free” (1881). When asked why the tune should be used like this, William Booth is said to have replied Why should the devil have all the good tunes? The people the Army sought to save, knew nothing of the hymn tunes or gospel melodies used in the churches, but’the music hall had been their melody school. By the 1870s, the songs were free of their folk music origins, and particular songs also started to become associated with particular singers, often with exclusive contracts with the songwriter, just as many pop songs are today. Towards the end of the style the music became influenced by ragtime and jazz, before being overtaken by them. Music hall songs were often composed with their working class audiences in mind. Songs like “My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)”, Wot Cher! Knocked’em in the Old Kent Road”, and “Waiting at the Church, expressed in melodic form situations with which the urban poor were familiar. Music hall songs could be romantic, patriotic, humorous or sentimental, as the need arose. [49] The most popular music hall songs became the basis for the pub songs of the typical Cockney “knees up”. Although a number of songs show a sharply ironic and knowing view of working class life, there were, too, those which were repetitive, derivative, written quickly and sung to make a living rather than a work of art. “If It Wasn’t for the’Ouses in Between”, sung by Gus Elen. See also: Music hall songs. A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good George Arthurs, Fred W. Leigh, sung by Marie Lloyd. “Any Old Iron” (Charles Collins; Terry Sheppard) sung by Harry Champion. “Ask a P’liceman” E. Durandeau sung by James Fawn. “Belgium Put the Kibosh on the Kaiser” (Alf Ellerton) sung by Mark Sheridan. “Boiled Beef and Carrots” (Charles Collins and Fred Murray) sung by Harry Champion. “The Boy I Love is Up in the Gallery” (George Ware) sung by Nelly Power, and Marie Lloyd. “Burlington Bertie from Bow” (William Hargreaves) sung by Ella Shields. “Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)” (Harry Dacre) sung by Katie Lawrence. “Don’t Dilly Dally on the Way” Charles Collins and Fred W. Leigh sung by Marie Lloyd. “Down at the Old Bull and Bush” Harry von Tilzer; Andrew B. Sterling sung by Florrie Forde. “Every Little Movement (Has a Meaning All Its Own)” J. Cliffe sung by Marie Lloyd. Weston; Bert Lee sung by Florrie Forde and Daisy Wood. Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly? Murphy and Will Letters sung by Florrie Forde. Hello, Hello, Who’s Your Lady Friend? (Harry Fragson; Worton David; Bert Lee) sung by Harry Fragson, Mark Sheridan, etc. “Hold Your Hand Out, Naughty Boy” C. “I Belong to Glasgow”, written and performed by Will Fyffe. “I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside” John A. Glover-Kind sung by Mark Sheridan. “I Was A Good Little Girl” Clifford F. Tate sung by Clarice Mayne and That. “If It Wasn’t For The’Ouses in Between” (George Le Brunn; Edgar Bateman) sung by Gus Elen. “It’s a Bit of a Ruin That Cromwell Knocked About a Bit” (Harry Bedford; Terry Sullivan) sung by Marie Lloyd. “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” (1914)[56] (Jack Judge and Harry Williams) sung by John McCormack. “Let’s All Go Down the Strand” Harry Castling and C. Murphy sung by Charles R. “Lily of Laguna” (Leslie Stuart) sung by Eugene Stratton, and later G. “The Man on the Flying Trapeze” George Leybourne; Gaston Lyle; arr. Alfred Lee sung by George Leybourne. “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo” (Fred Gilbert) sung by Charles Coborn. “My Old Dutch” (Albert Chevalier; Charles Ingle) sung by Albert Chevalier. “Nellie Dean” Henry W. Armstrong sung by Gertie Gitana. “Oh, It’s a Lovely War” J. Long; Maurice Scott sung by Ella Shields. Mr Porter (George Le Brunn and Thomas Le Brunn) sung by Marie Lloyd, and Norah Blaney. “Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag” (Felix Powell) sung by Florrie Forde. (All the Nice Girls Love a Sailor), performed by Hetty King. “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay” Harry J. Sayers sung by Lottie Collins. “Waiting at the Church”[57] Henry E. Leigh sung by Vesta Victoria. Where Did You Get That Hat? Sullivan, 1888; words rewritten 1901 by James Rolmaz[58] sung by J. Who Were You With Last Night? (Fred Godfrey; Mark Sheridan) sung by Mark Sheridan. 1949, lyricist of “Our Lodger’s Such A Nice Young Man” sung by Vesta Victoria. Frederick Bowyer (dates not known), with Orlando Powell re-wrote Charles Harris’s “After the Ball” for Vesta Tilley. Whittle and “Don’t Have Any More, Mrs More” sung by Lily Morris. ” sung by Mark Sheridan and “Hold Your Hand Out, Naughty Boy sung by Florrie Forde. ” sung by Mark Sheridan, and “Now I Have To Call Him Father sung by Vesta Victoria. Eric Graham (dates not known), composer of “The Golden Dustman” sung by Gus Elen. Tate of “I Was A Good Little Girl” and “A Broken Doll”, both sung by Clarice Mayne and That. MacDermott’s “War Song” By Jingo if we do… Charles Knight (dates not known), composer of “Here We Are, Here We Are Again” sung by Mark Sheridan. Mr Porter” sung by Marie Lloyd, and “If It Wasn’t for the’Ouses in Between” and “It’s a Great Big Shame sung by Gus Elen. Sung by Mark Sheridan. Kenneth Lyle (dates not known), composer of “Here We Are, Here We Are Again” sung by Mark Sheridan, [79] and “Jolly Good Luck to the Girl Who Loves a Soldier” sung by Vesta Tilley. (All The Nice Girls Love A Sailor) sung by Hetty King. Richard Morton (dates not known), lyricist of Twiggy Voo? ” and “Poor Thing, both sung by Marie Lloyd. ” sung by Florrie Forde and “Hello Hello, Who’s Your Lady Friend? Norris (dates not known), wrote the original “Burlington Bertie” (1900) for Vesta Tilley. Henry Pether (dates not known), composer of “Waiting at the Church” sung by Vesta Victoria. , both sung by Marie Lloyd. All the Nice Girls Love a Sailor sung by Ella Retford. The typical music hall comedian was a man or woman, usually dressed in character to suit the subject of the song, or sometimes attired in absurd and eccentric style. Until well into the twentieth century, the acts were essentially vocal, with songs telling a story, accompanied by a minimum of patter. They included a variety of genres, including. Lion comiques: essentially, men dressed as “toffs”, who sang songs about drinking champagne, going to the races, going to the ball, womanising and gambling, and living the life of an aristocrat. Male and female impersonators, the latter more in the style of a pantomime dame than a modern drag queen. Nevertheless, these included some more sophisticated performers such as Vesta Tilley and Ella Shields, whose male impersonations communicated real social commentary. Male impersonator Hetty King. The vocal content of the music hall bills, was, from the beginning, accompanied by many other kinds of act, some of them quite weird and wonderful. These were known collectively as speciality acts (abbreviated to “spesh”), which, over time, have included. Adagio: essentially a sort of cross between a dance act and a juggling act, consisting usually of a male dancer who threw a slim, pretty young girl around. Some aspects of modern dance choreography evolved from Adagio acts. Aerial acts, of the sort usually seen at the circus. Animal acts: Talking dogs, flea circuses, and all manner of animals doing tricks. Cycling acts: again, a development of a circus act, consisting of either a solo or a troupe of trick cyclists. There was even a seven-piece cycling band called Seven Musical Savonas, who played fifty instruments between them, and Kaufmann’s Cycling Beauties, a troupe of girls in Victorian swim wear. Drag artists: female entertainers dressed as men, such as Vesta Tilley, Ella Shields, and Hetty King; or male entertainers dressed as women, such as Bert Erroll, Julian Eltinge, Danny La Rue, and Rex Jameson in the character of Mrs Shufflewick. Electric acts, using the newly discovered phenomenon of static electricity to produce tricks such as lighting gas jets and setting fire to handkerchiefs through the performers fingertips. Dr Walford Brodie (1869/70-1939) was the most notable. Escapologists, such as Harry Houdini. Fire eaters and other eating acts, such as eating glass, razor blades, goldfish, etc. Juggling and plate spinning acts. Another variation was the Diabolo. Knife throwing and sword swallowing. The most spectacular of its time was the Victorina Troupe, who swallowed a sword fired from a rifle. Magic acts, such as David Devant. Commonly a male mentalist, blindfolded on stage, and an attractive female assistant passing among the audience. The assistant would collect objects from the audience, and the mentalist would identify each by “reading” the assistants mind. This was usually accomplished by a clever system of codes and clues from the assistant. Mime artists and impressionists. Comic pianists, such as John Orlando Parry and George Grossmith. Puppet acts, including human puppets and living doll acts. Strongmen such as Eugen Sandow, and strongwomen such as Joan Rhodes, performing feats of strength. Ventriloquists, or Vent acts as they were called in the business, such as Fred Russell, Arthur Prince, Coram (Thomas Mitchell). Wrestling and jujitsu exhibitions were both popular speciality acts, forming the basis of modern professional wrestling. Not strictly a Music Hall, but a theatre where many of these artists performed their Music Hall acts. See also: List of British music hall performers. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Autographs\Celebrities”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Republic of Croatia, Malaysia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion.