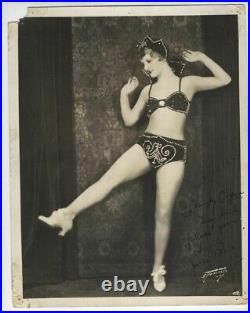

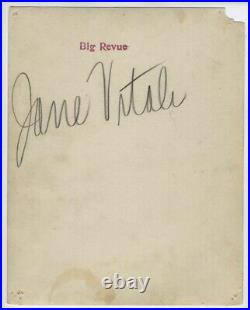

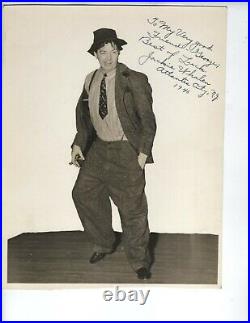

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 7.5X9.5 INCH PHOTO SIGNED BY JACKIE WHALEN from 1940. To My Very good. Jackie Whalen, who was a producer, comic and emcee in burlesque and night clubs from the late 1930s through the early 1950s. Jackie had performed with Eddie White (who also made a memorable Vitaphone) in Atlantic City in the’40s. Incidentally, there was a Jackie Whalen, who was a producer, comic and emcee in burlesque and night clubs from the late 1930s through the early 1950s. I haven’t been able to ascertain yet whether Harold and Jackie were related. JACKIE WHALEN’S second summer at the Club Nomad, Atlantic City, will. Have reached its 11th week August 23. It was 22 in all in. Dancer, came in August 9. MIDGLEY is playing the part of the. Barker in the play of that name, in. Which Ann Corio is featured. The company in Fitchburg, Mass. The Lake Whalom Theater and has been. Playing leads all season. Letter, It’s nice to cross paths on the. DIANE ROWLAND annexed a substantial raise at the 606 Club. Fran White vacationing at Milford. And storied in the Daily Mirror August. 13 concerning her Saturday night din- ners for servicemen in Los Angeles. SAM FUNT, Gaiety’s manager, together. Funt, vacationing at Kaimesha. JEAN LEE new at the. A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. [1] The word derives from the Italian burlesco, which, in turn, is derived from the Italian burla – a joke, ridicule or mockery. Burlesque overlaps in meaning with caricature, parody and travesty, and, in its theatrical sense, with extravaganza, as presented during the Victorian era. [4] “Burlesque” has been used in English in this literary and theatrical sense since the late 17th century. It has been applied retrospectively to works of Chaucer and Shakespeare and to the Graeco-Roman classics. [5] Contrasting examples of literary burlesque are Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock and Samuel Butler’s Hudibras. An example of musical burlesque is Richard Strauss’s 1890 Burleske for piano and orchestra. Examples of theatrical burlesques include W. Gilbert’s Robert the Devil and the A. Torr – Meyer Lutz shows, including Ruy Blas and the Blasé Roué. A later use of the term, particularly in the United States, refers to performances in a variety show format. These were popular from the 1860s to the 1940s, often in cabarets and clubs, as well as theatres, and featured bawdy comedy and female striptease. Some Hollywood films attempted to recreate the spirit of these performances from the 1930s to the 1960s, or included burlesque-style scenes within dramatic films, such as 1972’s Cabaret and 1979’s All That Jazz, among others. There has been a resurgence of interest in this format since the 1990s. Literary origins and development. Arabella Fermor, target of The Rape of the Lock. The word first appears in a title in Francesco Berni’s Opere burlesche of the early 16th century, works that had circulated widely in manuscript before they were printed. For a time, burlesque verses were known as poesie bernesca in his honour. Burlesque’ as a literary term became widespread in 17th century Italy and France, and subsequently England, where it referred to a grotesque imitation of the dignified or pathetic. [8] Shakespeare’s Pyramus and Thisbe scene in Midsummer Night’s Dream and the general mocking of romance in Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle were early examples of such imitation. In 17th century Spain, playwright and poet Miguel de Cervantes ridiculed medieval romance in his many satirical works. Among Cervantes’ works are Exemplary Novels and the Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes published in 1615. [10] The term burlesque has been applied retrospectively to works of Chaucer and Shakespeare and to the Graeco-Roman classics. Burlesque was intentionally ridiculous in that it imitated several styles and combined imitations of certain authors and artists with absurd descriptions. In this, the term was often used interchangeably with “pastiche”, “parody”, and the 17th and 18th century genre of the “mock-heroic”. [11] Burlesque depended on the reader’s (or listener’s) knowledge of the subject to make its intended effect, and a high degree of literacy was taken for granted. 17th and 18th century burlesque was divided into two types: High burlesque refers to a burlesque imitation where a literary, elevated manner was applied to a commonplace or comically inappropriate subject matter as, for example, in the literary parody and the mock-heroic. One of the most commonly cited examples of high burlesque is Alexander Pope’s “sly, knowing and courtly” The Rape of the Lock. [13] Low burlesque applied an irreverent, mocking style to a serious subject; an example is Samuel Butler’s poem Hudibras, which described the misadventures of a Puritan knight in satiric doggerel verse, using a colloquial idiom. Butler’s addition to his comic poem of an ethical subtext made his caricatures into satire. In more recent times, burlesque true to its literary origins is still performed in revues and sketches. [9] Tom Stoppard’s 1974 play Travesties is an example of a full-length play drawing on the burlesque tradition. See also: Parody music. Beginning in the early 18th century, the term burlesque was used throughout Europe to describe musical works in which serious and comic elements were juxtaposed or combined to achieve a grotesque effect. [16] As derived from literature and theatre, “burlesque” was used, and is still used, in music to indicate a bright or high-spirited mood, sometimes in contrast to seriousness. In this sense of farce and exaggeration rather than parody, it appears frequently on the German-language stage between the middle of the 19th century and the 1920s. Burlesque operettas were written by Johann Strauss II (Die lustigen Weiber von Wien, 1868), [17] Ziehrer (Mahomed’s Paradies, 1866; Das Orakel zu Delfi, 1872; Cleopatra, oder Durch drei Jahrtausende, 1875; In fünfzig Jahren, 1911)[18] and Bruno Granichstaedten (Casimirs Himmelfahrt, 1911). French references to burlesque are less common than German, though Grétry composed for a “drame burlesque” (Matroco, 1777). [19] Stravinsky called his 1916 one-act chamber opera-ballet Renard (The Fox) a “Histoire burlesque chantée et jouée” (burlesque tale sung and played) and his 1911 ballet Petrushka a “burlesque in four scenes”. A later example is the 1927 burlesque operetta by Ernst Krenek entitled Schwergewicht (Heavyweight) (1927). Burleske (1885-86), by Richard Strauss. Performed by Neal O’Doan with the Seattle Philharmonic Orchestra. Problems playing this file? Some orchestral and chamber works have also been designated as burlesques, of which two early examples are the Ouverture-Suite Burlesque de Quixotte, TWV 55, by Telemann and the Sinfonia Burlesca by Leopold Mozart (1760). Another often-performed piece is Richard Strauss’s 1890 Burleske for piano and orchestra. [16] Other examples include the following. 1901: Six Burlesques, Op. 58 for piano four hands by Max Reger. 1904: Scherzo Burlesque, Op. 2 for piano and orchestra by Béla Bartók. 1911: Three Burlesques, Op. 8c for piano by Bartók. 1920: Burlesque for Piano, by Arnold Bax. 1931: Ronde burlesque, Op. 78 for orchestra by Florent Schmitt. 1932: Fantaisie burlesque, for piano by Olivier Messiaen. 1956: Burlesque for Piano and Chamber Orchestra, Op. 13g by Bertold Hummel. 1982: Burlesque for Wind Quintet, Op. Burlesque can be used to describe particular movements of instrumental musical compositions, often involving dance rhythms. Examples are the Burlesca, in Partita No. 3 for keyboard (BWV 827) by Bach, the “Rondo-Burleske” third movement of Symphony No. 9 by Mahler, and the “Burlesque” fourth movement of Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. The use of burlesque has not been confined to classical music. Well-known ragtime travesties include Russian Rag, by George L. Cobb, which is based on Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp minor, and Harry Alford’s Lucy’s Sextette based on the sextet,’Chi mi frena in tal momento? , from Lucia di Lammermoor by Donizetti. John in Carmen up to Data. Main article: Victorian burlesque. Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as “travesty” or “extravaganza”, [22] was popular in London theatres between the 1830s and the 1890s. It took the form of musical theatre parody in which a well-known opera, play or ballet was adapted into a broad comic play, usually a musical play, often risqué in style, mocking the theatrical and musical conventions and styles of the original work, and quoting or pastiching text or music from the original work. The comedy often stemmed from the incongruity and absurdity of the classical subjects, with realistic historical dress and settings, being juxtaposed with the modern activities portrayed by the actors. Madame Vestris produced burlesques at the Olympic Theatre beginning in 1831 with Olympic Revels by J. [23] Other authors of burlesques included H. Gilbert and Fred Leslie. Victorian burlesque related to and in part derived from traditional English pantomime with the addition of gags and’turns’. [25] In the early burlesques, following the example of ballad opera, the words of the songs were written to popular music;[26] later burlesques mixed the music of opera, operetta, music hall and revue, and some of the more ambitious shows had original music composed for them. This English style of burlesque was successfully introduced to New York in the 1840s. Sheet music from Faust up to Date. Some of the most frequent subjects for burlesque were the plays of Shakespeare and grand opera. [28][29] The dialogue was generally written in rhyming couplets, liberally peppered with bad puns. [25] A typical example from a burlesque of Macbeth: Macbeth and Banquo enter under an umbrella, and the witches greet them with Hail! ” Macbeth asks Banquo, “What mean these salutations, noble thane? ” and is told, “These showers of’Hail’ anticipate your’reign’. [29] A staple of burlesque was the display of attractive women in travesty roles, dressed in tights to show off their legs, but the plays themselves were seldom more than modestly risqué. Programme: Ruy Blas and the Blasé Roué. Burlesque became the speciality of certain London theatres, including the Gaiety and Royal Strand Theatre from the 1860s to the early 1890s. Until the 1870s, burlesques were often one-act pieces running less than an hour and using pastiches and parodies of popular songs, opera arias and other music that the audience would readily recognize. The house stars included Nellie Farren, John D’Auban, Edward Terry and Fred Leslie. [24][30] From about 1880, Victorian burlesques grew longer, until they were a whole evening’s entertainment rather than part of a double- or triple-bill. [24] In the early 1890s, these burlesques went out of fashion in London, and the focus of the Gaiety and other burlesque theatres changed to the new more wholesome but less literary genre of Edwardian musical comedy. Advertisement for a burlesque troupe, 1898. Main article: American burlesque. American burlesque shows were originally an offshoot of Victorian burlesque. The English genre had been successfully staged in New York from the 1840s, and it was popularised by a visiting British burlesque troupe, Lydia Thompson and the “British Blondes”, beginning in 1868. [32] New York burlesque shows soon incorporated elements and the structure of the popular minstrel shows. They consisted of three parts: first, songs and ribald comic sketches by low comedians; second, assorted olios and male acts, such as acrobats, magicians and solo singers; and third, chorus numbers and sometimes a burlesque in the English style on politics or a current play. The entertainment was usually concluded by an exotic dancer or a wrestling or boxing match. The entertainments were given in clubs and cabarets, as well as music halls and theatres. By the early 20th century, there were two national circuits of burlesque shows competing with the vaudeville circuit, as well as resident companies in New York, such as Minsky’s at the Winter Garden. [33] The transition from burlesque on the old lines to striptease was gradual. At first, soubrettes showed off their figures while singing and dancing; some were less active but compensated by appearing in elaborate stage costumes. [34] The strippers gradually supplanted the singing and dancing soubrettes; by 1932 there were at least 150 strip principals in the US. [34] Star strippers included Sally Rand, Gypsy Rose Lee, Tempest Storm, Lili St. Cyr, Blaze Starr, Ann Corio and Margie Hart, who was celebrated enough to be mentioned in song lyrics by Lorenz Hart and Cole Porter. [34] By the late 1930s, burlesque shows would have up to six strippers supported by one or two comics and a master of ceremonies. Comics who appeared in burlesque early in their careers included Fanny Brice, Mae West, Eddie Cantor, Abbott and Costello, W. Fields, Jackie Gleason, Danny Thomas, Al Jolson, Bert Lahr, Phil Silvers, Sid Caesar, Danny Kaye, Red Skelton and Sophie Tucker. Michelle L’amour, 2005 Miss Exotic World. The uninhibited atmosphere of burlesque establishments owed much to the free flow of alcoholic liquor, and the enforcement of Prohibition was a serious blow. [35] In New York, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia clamped down on burlesque, effectively putting it out of business by the early 1940s. [36] It lingered on elsewhere in the U. Increasingly neglected, and by the 1970s, with nudity commonplace in theatres, reached its final shabby demise. [37] Both during its declining years and afterwards there have been films that sought to capture American burlesque, including Lady of Burlesque (1943), [38] Striporama (1953), [39] and The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968). The “Stage Door Johnnies” performing at the Burlesque Hall of Fame in Las Vegas, 2011. In recent decades, there has been a revival of burlesque, sometimes called Neo-Burlesque, [36] on both sides of the Atlantic. [41] A new generation, nostalgic for the spectacle and perceived glamour of the classic American burlesque, developed a cult following for the art in the early 1990s at Billie Madley’s “Cinema” and later at the “Dutch Weismann’s Follies” revues in New York City, “The Velvet Hammer” troupe in Los Angeles and The Shim-Shamettes in New Orleans. Ivan Kane’s Royal Jelly Burlesque Nightclub at Revel Atlantic City opened in 2012. [42] Notable Neo-burlesque performers include Dita Von Teese, and Julie Atlas Muz and Agitprop groups like Cabaret Red Light incorporated political satire and performance art into their burlesque shows. Annual conventions such as the Vancouver International Burlesque Festival and the Miss Exotic World Pageant are held. Atlantic City, often known by its initials A. Is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States, known for its casinos, boardwalk, and beaches. In 2010, the city had a population of 39,558. [12][13][14][23][24] It was incorporated on May 1, 1854, from portions of Egg Harbor Township and Galloway Township. [25] It borders Absecon, Brigantine, Pleasantville, Ventnor City, Egg Harbor Township, and the Atlantic Ocean. Atlantic City inspired the U. Version of the board game Monopoly, especially the street names. Since 1921, Atlantic City has been the home of the Miss America pageant. In 1976, New Jersey voters legalized casino gambling in Atlantic City. The first casino opened two years later. Sports betting in Atlantic City. Mayoral disappearance and resignation. Federal, state and county representation. City and state agencies. New Jersey Casino Control Commission. New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement. Casino Reinvestment Development Authority. Atlantic City Convention and Visitors Authority. Atlantic City Special Improvement District. A High Tide at Atlantic City by William Trost Richards is housed in the Brooklyn Museum. Because of its location in South Jersey, hugging the Atlantic Ocean between marshlands and islands, Atlantic City was viewed by developers as prime real estate and a potential resort town. In 1853, the first commercial hotel, the Belloe House, was built at the intersection of Massachusetts and Atlantic Avenues. [26] The city was incorporated in 1854, the same year train service began on the Camden and Atlantic Railroad. [27] Built on the edge of the bay, this served as the direct link of this remote parcel of land with Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. That same year, construction of the Absecon Lighthouse, designed by George Meade of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, was approved, with work initiated the next year. [28] By 1874, almost 500,000 passengers a year were coming to Atlantic City by rail. In Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times, and Corruption of Atlantic City, “Atlantic City’s Godfather”[29] Nelson Johnson describes the inspiration of Dr. Jonathan Pitney (the “Father of Atlantic City”[30]) to develop Atlantic City as a health resort, his efforts to convince the municipal authorities that a railroad to the beach would be beneficial, his successful alliance with Samuel Richards (entrepreneur and member of the most influential family in southern New Jersey at the time) to achieve that goal, the actual building of the railroad, and the experience of the first 600 riders, who “were chosen carefully by Samuel Richards and Jonathan Pitney”:[31]. After arriving in Atlantic City, a second train brought the visitors to the door of the resort’s first public lodging, the United States Hotel. The hotel was owned by the railroad. It was a sprawling, four-story structure built to house 2,000 guests. It opened while it was still under construction, with only one wing standing, and even that wasn’t completed. By year’s end, when it was fully constructed, the United States Hotel was not only the first hotel in Atlantic City but also the largest in the nation. Its rooms totaled more than 600, and its grounds covered some 14 acres. The first boardwalk was built in 1870 along a portion of the beach in an effort to help hotel owners keep sand out of their lobbies. Businesses were restricted and the boardwalk was removed each year at the end of the peak season. [32] Because of its effectiveness and popularity, the boardwalk was expanded in length and width, and modified several times in subsequent years. The historic length of the boardwalk, before the destructive 1944 Great Atlantic Hurricane, was about 7 miles (11 km) and it extended from Atlantic City to Longport, through Ventnor and Margate. The first road connecting the city to the mainland at Pleasantville was completed in 1870 and charged a 30-cent toll. Albany Avenue was the first road to the mainland available without a toll. By 1878, because of the growing popularity of the city, one railroad line could no longer keep up with demand. Soon, the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway was also constructed to transport tourists to Atlantic City. At this point massive hotels like The United States and Surf House, as well as smaller rooming houses, had sprung up all over town. The United States Hotel took up a full city block between Atlantic, Pacific, Delaware, and Maryland Avenues. These hotels were not only impressive in size, but featured the most updated amenities, and were considered quite luxurious for their time. Haddon Hall Hotel depicted on a postcard. In the early part of the 20th century, Atlantic City went through a radical building boom. Many of the modest boarding houses that dotted the boardwalk were replaced with large hotels. Two of the city’s most distinctive hotels were the Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel and the Traymore Hotel. In 1903, Josiah White III bought a parcel of land near Ohio Avenue and the boardwalk and built the Queen Anne style Marlborough House. The hotel was a success and, in 1905-06, he chose to expand the hotel and bought another parcel of land adjacent to his Marlborough House. In an effort to make his new hotel a source of conversation, White hired the architectural firm of Price and McLanahan. The firm made use of reinforced concrete, a new building material invented by Jean-Louis Lambot in 1848 (Joseph Monier received the patent in 1867). The hotel’s Spanish and Moorish themes, capped off with its signature dome and chimneys, represented a step forward from other hotels that had a classically designed influence. White named the new hotel the Blenheim and merged the two hotels into the Marlborough-Blenheim. Bally’s Atlantic City was later constructed at this location. Atlantic City Boardwalk crowd in front of Blenheim hotel, 1911 (retouched). The Traymore Hotel was located at the corner of Illinois Avenue and the boardwalk. Begun in 1879 as a small boarding house, the hotel grew through a series of uncoordinated expansions. By 1914, the hotel’s owner, Daniel White, taking a hint from the Marlborough-Blenheim, commissioned the firm of Price and McLanahan to build an even bigger hotel. Rising 16 stories, the tan brick and gold-capped hotel would become one of the city’s best-known landmarks. The hotel made use of ocean-facing hotel rooms by jutting its wings farther from the main portion of the hotel along Pacific Avenue. One by one, additional large hotels were constructed along the boardwalk, including the Brighton, Chelsea, Shelburne, Ambassador, Ritz Carlton, Mayflower, Madison House, and the Breakers. The Quaker-owned Chalfonte House, opened in 1868, and Haddon House, opened in 1869, flanked North Carolina Avenue at the beach end. Over the years, their original wood-frame structures would be enlarged, and even moved closer to the beach. The modern Chalfonte Hotel, eight stories tall, opened in 1904. The modern Haddon Hall was built in stages and was completed in 1929, at eleven stories. By this time, they were under the same ownership and merged into the Chalfonte-Haddon Hall Hotel, becoming the city’s largest hotel with nearly 1,000 rooms. By 1930, the Claridge, the city’s last large hotel before the casinos, opened its doors. The 400-room Claridge was built by a partnership that included renowned Philadelphia contractor John McShain. At 24 stories, it would become known as the Skyscraper by the Sea. ” The city became known as “The World’s Playground. In 1883, salt water taffy was conceived in Atlantic City by David Bradley. The traditional story is that Bradley’s shop was flooded after a major storm, soaking his taffy with salty Atlantic Ocean water. Bradley’s mother was in the back of the store when the sale was made, and loved the name, and so salt water taffy was born. Consilio et prudentia, Atlantic City’s motto, along with its coat of arms on historic Boardwalk Hall, built during Prohibition. The 1920s, with tourism at its peak, are considered by many historians as Atlantic City’s golden age. During Prohibition, which was enacted nationally in 1919 and lasted until 1933, much liquor was consumed and gambling regularly took place in the back rooms of nightclubs and restaurants. It was during Prohibition that racketeer and political boss Enoch L. “Nucky” Johnson rose to power. Prohibition was largely unenforced in Atlantic City, and, because alcohol that had been smuggled into the city with the acquiescence of local officials could be readily obtained at restaurants and other establishments, the resort’s popularity grew further. [39] The city then dubbed itself as “The World’s Playground”. During this time, Atlantic City was led by mayor Edward L. Bader, known for his contributions to the construction, athletics and aviation of Atlantic City. [42] He led the initiative, in 1923, to construct the Atlantic City High School at Albany and Atlantic Avenues. [41] Bader, in November 1923, initiated a public referendum, during the general election, at which time residents approved the construction of a Convention Center. [43] Bader was also a driving force behind the creation of the Miss America competition. In May 1929, Johnson hosted a conference for organized crime figures from all across America that created a National Crime Syndicate. The men who called this meeting were Masseria family lieutenant Charles “Lucky” Luciano and former Chicago South Side Gang boss Johnny “the Fox” Torrio, with heads of the Bugs and Meyer Mob, Meyer Lansky and Benjamin Siegel, being used as muscle for the meeting. [45] Gangster and businessman Al Capone attended the conference and was photographed walking along the Atlantic City boardwalk with Johnson. The 1930s through the 1960s were a heyday for nightclub entertainment. Popular venues on the white-populated south side included the 500 Club, the Clicquot Club, and the Jockey Club. On the north side, home to African Americans in the racially segregated city, a black entertainment district reigned on Kentucky Avenue. Four major nightclubs – Club Harlem, the Paradise Club, Grace’s Little Belmont, and Wonder Gardens – drew both black and white patrons. During the summer tourist season, jazz and R&B music could be heard into the wee hours of the morning. Soul food restaurants and ribs joints also lined Kentucky Avenue, including Wash’s Restaurant, [47] Jerry’s and Sap’s. The Tropicana from the boardwalk. Like many older east coast cities after World War II, Atlantic City became plagued with poverty, crime, corruption, and general economic decline in the mid-to-late 20th century. The neighborhood known as the “Inlet” became particularly impoverished. The reasons for the resort’s decline were multi-layered. First, the automobile became more readily available to many Americans after the war. Atlantic City had initially relied upon visitors coming by train and staying for a couple of weeks. The car allowed them to come and go as they pleased, and many people would spend only a few days, rather than weeks. The advent of suburbia also played a significant role. With many families moving to their own private houses, luxuries such as home air conditioning and swimming pools diminished their interest in flocking to the luxury beach resorts during the hot summer. Finally, the rise of relatively cheap jet airline service allowed visitors to travel to year-round resort cities such as Miami Beach and the Bahamas. View of Trump Taj Mahal and Chairman Tower from the Boardwalk. The city hosted the 1964 Democratic National Convention which nominated Lyndon Johnson for president and Hubert Humphrey as vice president. The convention and the press coverage it generated, however, cast a harsh light on Atlantic City, which by then was in the midst of a long period of economic decline. Many felt that the friendship between Johnson and Governor of New Jersey Richard J. Hughes led Atlantic City to host the Democratic Convention. By the late 1960s, many of the resort’s once great hotels were suffering from high vacancy rates. Most of them were either shut down, converted to cheap apartments, or converted to nursing home facilities by the end of the decade. Prior to and during the advent of legalized gambling, many of these hotels were demolished. The Breakers, The Chelsea, the Brighton, the Shelburne, the Mayflower, the Traymore and the Marlborough-Blenheim were demolished in the 1970s and 1980s. Of the many pre-casino resorts that bordered the boardwalk, only the Claridge, the Dennis, the Ritz-Carlton, and the Haddon Hall survive to this day as parts of Bally’s Atlantic City, a condo complex, and Resorts Atlantic City. [51] Smaller hotels off the boardwalk, such as the Madison also survived. The Borgata is Atlantic City’s highest grossing casino. Main article: Gambling in New Jersey. In an effort at revitalizing the city, New Jersey voters in 1976 passed a referendum, approving casino gambling for Atlantic City; this came after a 1974 referendum on legalized gambling failed to pass. Immediately after the legislation passed, the owners of the Chalfonte-Haddon Hall Hotel began converting it into the Resorts International. It was the first legal casino in the eastern United States when it opened on May 26, 1978. [52] Other casinos were soon constructed along the Boardwalk and, later, in the marina district for a total of eleven today. The introduction of gambling did not, however, quickly eliminate many of the urban problems that plagued Atlantic City. Many people have suggested that it only served to exacerbate those problems, as attested to by the stark contrast between tourism intensive areas and the adjacent impoverished working-class neighborhoods. [53] In addition, Atlantic City has been less popular than Las Vegas as a gambling city in the United States. [54] Donald Trump helped bring big name boxing bouts to the city to attract customers to his casinos. The boxer Mike Tyson had most of his fights in Atlantic City in the 1980s, which helped Atlantic City achieve nationwide attention as a gambling resort. [55] Numerous highrise condominiums were built for use as permanent residences or second homes. [56] By end of the decade it was one of the most popular tourist destinations in the United States. On June 27, 2017, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Christie v. National Collegiate Athletic Association and heard oral arguments in December 2017. Then, on May 14, 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) was unconstitutional. The act was overturned, allowing New Jersey to move ahead with plans to implement legalized sports betting. Despite being the state to initiate the landmark ruling, New Jersey was actually the third state to legalize sports betting following Nevada and Delaware. Phil Murphy signed the legislation into law on June 11, 2018, prompting several casino brands to launch sportsbooks, particularly in Atlantic City. Night time view of Atlantic City. With the redevelopment of the Las Vegas Strip and the opening of Foxwoods Resort Casino and Mohegan Sun in Connecticut in the early 1990s, along with newly built casinos in the nearby Philadelphia metro area in the 2000s, Atlantic City’s tourism began to decline due to its failure to diversify away from gaming. Determined to expand, in 1999 the Atlantic City Redevelopment Authority partnered with Las Vegas casino mogul Steve Wynn to develop a new roadway to a barren section of the city near the Marina. The roadway was later officially named the Atlantic City-Brigantine Connector, and funnels incoming traffic off of the expressway into the city’s marina district and the city of Brigantine. Although Wynn’s plans for development in the city were scrapped in 2002, the tunnel opened in 2001. The new roadway prompted Boyd Gaming in partnership with MGM/Mirage to build Atlantic City’s newest casino. The Borgata opened in July 2003, and its success brought an influx of developers to Atlantic City with plans for building grand Las Vegas style mega casinos to revitalize the aging city. Owing to economic conditions and the late 2000s recession, many of the proposed mega casinos never went further than the initial planning stages. [60][61] The following year, the resort was demolished in a dramatic, Las Vegas styled implosion, the first of its kind in Atlantic City. [61] MGM Resorts International announced in October 2007 that it would pull out of all development for Atlantic City, effectively ending their plans for the MGM Grand Atlantic City. [64] Revel Entertainment Group was named as the project’s developer for the Revel Casino. Revel was hindered with many problems, the biggest setback occurring in April 2010 when Morgan Stanley, the owner of 90% of Revel Entertainment Group, decided to discontinue funding for continued construction and put its stake in Revel up for sale. [67] As of March 2011, Revel had completed all of the exterior work and had continued work on the interior after finally receiving the funding necessary to complete construction. It had a soft opening in April 2012, and was fully open by May 2012. It was restructured but still could not carry on and re-entered bankruptcy on June 19, 2014. In the wake of the closures and declining revenue from casinos, Governor Christie said in September 2014 that the state would consider a 2015 referendum to end the 40-year-old monopoly that Atlantic City holds on casino gambling and allowing gambling in other municipalities. “Superstorm Sandy” struck Atlantic City on October 29, 2012, causing flooding and power-outages but left minimal damage to any of the tourist areas including the Boardwalk and casino resorts, despite widespread belief that the city’s boardwalk had been destroyed. The source of the misinformation was a widely circulated photograph of a damaged section of the Boardwalk that was slated for repairs, prior to the storm, and incorrect news reports at the time of the disaster. [71] The storm produced an all-time record low barometric pressure reading of 943 mb (27.85) for not only Atlantic City, but the state of New Jersey. According to the United States Census Bureau, Atlantic City had a total area of 17.21 square miles (44.59 km2), including 10.76 square miles (27.87 km2) of land and 6.45 square miles (16.72 km2) of water (37.50%). The city is located on 8.1-mile-long (13.0 km) Absecon Island, along with Ventnor City, Margate City and Longport to the southwest. Atlantic City borders the Atlantic County municipalities of Absecon, Brigantine, Egg Harbor Township, Galloway Township, Pleasantville and Ventnor City. The city is located 60 miles (97 km) southeast of Philadelphia and 125 miles (201 km) south of New York City. Unincorporated communities, localities and place names located partially or completely within the city include Chelsea, City Island, Great Island and Venice Park. Places adjacent to Atlantic City, New Jersey. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Atlantic City, New Jersey, has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with warm, moderately humid summers, cool winters and year-around precipitation. Cfa climates are characterized by all months having an average mean temperature > 32 °F (> 0 °C), at least four months with an average mean temperature? 50 °F (? 10 °C), at least one month with an average mean temperature? 72 °F (? 22 °C) and no significant precipitation difference between seasons. During the summer months in Atlantic City, a cooling afternoon sea breeze is present on most days, but episodes of extreme heat and humidity can occur with heat index values? 95 °F (? 35 °C). During the winter months, episodes of extreme cold and wind can occur with wind chill values. Climate data for Atlantic City, NJ Ocean Water Temperature. Daily mean °F (°C). According to the A. Potential natural vegetation types, Atlantic City would have a dominant vegetation type of Northern Cordgrass (73) with a dominant vegetation form of Coastal Prairie (20). The 2010 United States Census counted 39,558 people, 15,504 households, and 8,558 families in the city. The population density was 3,680.8 per square mile (1,421.2/km2). There were 20,013 housing units at an average density of 1,862.2 per square mile (719.0/km2). The racial makeup was 26.65% (10,543) White, 38.29% (15,148) Black or African American, 0.61% (242) Native American, 15.55% (6,153) Asian, 0.05% (18) Pacific Islander, 14.03% (5,549) from other races, and 4.82% (1,905) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 30.45% (12,044) of the population. Of the 15,504 households, 27.3% had children under the age of 18; 25.9% were married couples living together; 22.2% had a female householder with no husband present and 44.8% were non-families. Of all households, 37.5% were made up of individuals and 14.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.50 and the average family size was 3.34. 24.6% of the population were under the age of 18, 10.2% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 25.8% from 45 to 64, and 12.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.3 years. For every 100 females, the population had 96.2 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 94.4 males. About 23.1% of families and 25.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 36.6% of those under age 18 and 16.8% of those age 65 or over. As of the 2000 United States Census[20] there were 40,517 people, 15,848 households, and 8,700 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,569.8 people per square mile (1,378.3/km2). There were 20,219 housing units at an average density of 1,781.4 per square mile (687.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 44.16% black or African American, 26.68% White, 0.48% Native American, 10.40% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 13.76% other races, and 4.47% from two or more races. 24.95% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 19.44% of the population was non-Hispanic whites. There were 15,848 households, out of which 27.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 24.8% were married couples living together, 23.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.1% were non-families. 37.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.26. In the city the age distribution of the population shows 25.7% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 31.0% from 25 to 44, 20.2% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.2 males. About 19.1% of families and 23.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.1% of those under age 18 and 18.9% of those age 65 or over. As of September 2014, the greater Atlantic City area had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country at 13.8%, out of labor force of around 141,000. In July 2010, Governor Chris Christie announced that a state takeover of the city and local government “was imminent”. Comparing regulations in Atlantic City to an “antique car”, Atlantic City regulatory reform is a key piece of Governor Chris Christie’s plan, unveiled on July 22, to reinvigorate an industry mired in a four-year slump in revenue and hammered by fresh competition from casinos in the surrounding states of Delaware, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and more recently, Maryland. In January 2011, Chris Christie announced the creation of the Atlantic City Tourism District, a state-run district encompassing the boardwalk casinos, the marina casinos, the Atlantic City Outlets, and Bader Field. [99][100] Fairleigh Dickinson University’s PublicMind poll surveyed New Jersey voters’ attitudes on the takeover. February 16, 2011, survey showed that 43% opposed the measure while 29% favored direct state oversight. [101] The poll also found that even South Jersey voters expressed opposition to the plan; 40% reported they opposed the measure and 37% reported they were in favor of it. On April 29, 2011, the boundaries for the state-run tourism district were set. The district would include heavier police presence, as well as beautification and infrastructure improvements. The CRDA would oversee all functions of the district and make changes to attract new businesses and attractions. New construction will be ambitious and may resort to eminent domain. The tourism district would comprise several key areas in the city; the Marina District, Ducktown, Chelsea, South Inlet, Bader Field, and Gardner’s Basin. Also included are 10 roadways that lead into the district, including several in the city’s northern end, or North Beach. Gardner’s Basin, which is home to the Atlantic City Aquarium, was initially left out of the tourism district, while a residential neighborhood in the Chelsea section was removed from the final boundaries, owing to complaints from the city. Also, the inclusion of Bader Field in the district was controversial and received much scrutiny from mayor Lorenzo Langford, who cast the lone “no” vote on the creation of the district citing its inclusion. In 1974, New Jersey voters voted 60%-40% against legalizing casino gambling at four sites statewide, but two years later approved by 56%-44% a new referendum which legalized casinos, but restricted them to Atlantic City. [105][106][107] Resorts Atlantic City was the first casino to open, in May 1978, with a ribbon-cutting ceremony featuring Governor of New Jersey Brendan Byrne. [108] Atlantic City is considered the “Gambling Capital of the East Coast”, and currently has nine large casinos. [109] They are regulated by the New Jersey Casino Control Commission[110] and the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement. In the wake of the United States’ economic downturn and the legalization of gambling in adjacent and nearby states (including Delaware, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania), four casino closures took place in 2014: the Atlantic Club on January 13; the Showboat on August 31;[112] the Revel, which was Atlantic City’s second-newest casino, on September 2;[113] and Trump Plaza, which originally opened in 1984, and was the poorest performing casino in the city, on September 16. [115] Trump Taj Mahal closed October 10, 2016, after failing to come to terms with union workers. Caesars Entertainment executives have been reconsidering the future of their three remaining Atlantic City properties (Bally’s, Caesars and Harrah’s), in the wake of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing by the company’s casino operating unit in January 2015. [117] In 2020, Bally’s Atlantic City was acquired by Bally’s Corporation. 100,000 sq ft. 145,000 sq ft. 225,756 sq ft. 160,000 sq ft. 125,935 sq ft. 74,252 sq ft. 161,000 sq ft. 167,000 sq ft. 130,000 sq ft. 1,144,943 sq ft. A The Wild Wild West Casino, which opened on July 2, 1997, and has an American Old West theme, was part of Bally’s Atlantic City until 2020, when it became part of Caesars. Atlantic Club Casino Hotel. Atlantic City Hilton (Original). Bally’s Park Place. Bally’s Atlantic City. Del Webb’s Claridge. Harrah’s at Trump Plaza. Playboy Hotel & Casino. Permanent casino license denied; renamed Atlantis Casino. The Atlantic City Hilton. Hard Rock Atlantic City. The casino shut down having failed to reach a deal with its union workers to restore health care and pension benefits that were taken away from them in bankruptcy court. Nearly 3,000 workers lost their jobs. Reopened in 2018 as the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino Atlantic City. [120] Carl Icahn, senior lender for Trump Plaza’s mortgage, declined to approve the sale for the proposed price. [123] It reopened as the Ocean Resort Casino in June 2018. However, a preexisting covenant required the property to operate as a casino. [125] The building was reopened in July 2016 as a non-casino hotel. In February 2011, sale approved in May and Landry’s took control on May 23 of that year and renamed it the Golden Nugget Atlantic City. Building demolished in 2007. Now operating as an independent non-casino hotel. Trump World’s Fair. Building was demolished and replaced by new strip stores. Originally opened by Playboy Enterprises, which was found unsuitable for licensure, Playboy casino closed and then reopened by Elsinor Corporation as the Atlantis. Cancelled; currently an empty lot. Never completed; now an empty lot. Casino license denied; current site of Golden Nugget Atlantic City. Cancelled; current site of Golden Nugget Atlantic City. MGM Grand Atlantic City. Never built; current site of Trump Plaza. Cancelled; current site of Taj Mahal. Cancelled; now a parking lot. Atlantic City Boardwalk, an entertainment venue. Boardwalk, travel poster 1936. Boardwalk from beach, 1936. Boardwalk at night, travel poster. Looking down on boardwalk, beach and distant pier at night, 1935. The Atlantic City boardwalk. The Atlantic City Boardwalk opened on June 26, 1870, [128] a temporary structure erected for the summer season that was the first boardwalk in the United States. The Boardwalk starts at Absecon Inlet in the north and runs along the beach south-west to the city limit 4 miles (6.4 km) away then continues 1 1? 2 miles (2.4 km) into Ventnor City. Casino/hotels front the boardwalk, as well as retail stores, restaurants, and amusements. Notable attractions include the Boardwalk Hall, House of Blues, and the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy destroyed the northern part of the boardwalk fronting Absecon Inlet, in the residential section called South Inlet. The oceanfront boardwalk in front of the Atlantic City casinos survived the storm with minimal damage. The Boardwalk has been home to several piers over the years. The first pier, Ocean Pier, was built in 1882. [133] It eventually fell into disrepair and was demolished. Another famous pier built during that time was Steel Pier, opened in 1898, which once billed itself as “The Showplace of the Nation”. It now operates as an amusement pier across from the Hard Rock. Captain John Lake Young opened “Young’s Million Dollar Pier” as an arcade hall in 1903, and on the seaward side “erected a marble mansion”, fronted by a formal garden, with lighting and landscaping designed by Young’s longtime friend Thomas Alva Edison. Young’s Million Dollar Pier, Atlantic City’s largest amusement pier during its time”, [31] was transformed into a shopping mall in the 1980s, known as “Shops on Ocean One. In 2006, the Ocean One mall was bought, renovated and re-branded as “The Pier Shops at Caesars” and in 2015, it was renamed Playground Pier. Garden Pier, located opposite Revel Atlantic City, once housed a movie theater, and is now home to the Atlantic City Historical Museum. Two other piers, an amusement pier named Steeplechase Pier and a Heinz 57-owned pier named Heinz Pier were destroyed in the 1944 Great Atlantic Hurricane. [136] Steeplechase was rebuilt after the hurricane, and survived into the casino era. The “Steeplechase Pier Heliport” on Steel Pier is named in its honor. Panoramic view of Playground Pier. The Quarter at Tropicana. Atlantic City has many different shopping districts and malls, many of which are located inside or adjacent to the casino resorts. Several smaller themed retail and dining areas in casino hotels include the Borgata Shops and The Shoppes at Water Club inside the Borgata, the Waterfront Shops inside of Harrah’s, Spice Road inside the Trump Taj Mahal, while Resorts Casino Hotel has a small collection of stores and restaurants. Major shopping malls are also located in and around Atlantic City. In Atlantic City, shops include. Playground Pier, an underwater-themed indoor high end shopping center located on the Million Dollar Pier formerly known as “Shops on Ocean One”. The four-story shopping mall contains themed floors. Tanger Outlets The Walk, an outdoor outlet shopping center spanning several blocks. The only outlet mall in Atlantic County, The Walk opened in 2003 and is undergoing an expansion. The Quarter at Tropicana, an old Havana-themed indoor shopping center at the Tropicana, which contains over 40 stores, restaurants, and nightclubs. The Atlantic City Convention Center. Boardwalk Hall, formally known as the “Historic Atlantic City Convention Hall”, is an arena in Atlantic City along the boardwalk. Boardwalk Hall was Atlantic City’s primary convention center until the opening of the Atlantic City Convention Center in 1997. The Atlantic City Convention Center includes 500,000 sq ft (46,000 m2) of showroom space, 5 exhibit halls, 45 meeting rooms with 109,000 sq ft (10,100 m2) of space, a garage with 1,400 parking spaces, and an adjacent Sheraton hotel. Both the Boardwalk Hall and Convention Center are operated by the Atlantic City Convention & Visitors Authority. Atlantic City (sometimes referred to as “Monopoly City”[1]) has become well-known over the years for its portrayal in the U. Version of the popular board game, Monopoly, in which properties on the board are named after locations in and near Atlantic City. While the original incarnation of the game did not feature Atlantic City, it was in Indianapolis that Ruth Hoskins learned the game, and took it back to Atlantic City. [139] After she arrived, Hoskins made a new board with Atlantic City street names, and taught it to a group of friends, who ultimately passed in on to Charles Darrow, who made some modifications to the game and claimed it as his own invention. Marvin Gardens, the leading yellow property on the board, is actually a misspelling of the original location name, “Marven Gardens”. The misspelling was said to have been introduced by Charles Todd and passed on when his home-made Monopoly board was copied by Charles Darrow and thence Parker Brothers. It was not until 1995 that Parker Brothers acknowledged this mistake and formally apologized to the residents of Marven Gardens for the misspelling, although the spelling error was not corrected. Some of the actual locations that correspond to board elements have changed since the game’s release. Illinois Avenue was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Charles Place no longer exists, as the Showboat Casino Hotel was developed where it once ran. The “Short Line” is believed to refer to the Shore Fast Line, a streetcar line that served Atlantic City. [143] The B&O Railroad did not serve Atlantic City. A booklet included with the reprinted 1935 edition states that the four railroads that served Atlantic City in the mid-1930s were the Jersey Central, the Seashore Lines, the Reading Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad. The actual “Electric Company” and “Water Works” serving the city are the Atlantic City Electric Company and the Atlantic City Municipal Utilities Authority, respectively. Lucy the Elephant in nearby Margate City. Ever since Atlantic City’s growth as a resort town, numerous attractions and tourist traps have originated in the city. A popular fixture in the early 20th century at the Steel Pier was horse diving, which was introduced by William “Doc” Carver. [144] The Steel Pier featured several other novelty attractions, including the Diving Bell, human high-divers and a water circus. [145][146] Advertisements for the Steel Pier in its heyday featured plaster sculptures set upon wooden bases along roads leading up to Atlantic City. [147] By the end of World War II, many animal demonstrations declined in popularity after criticisms of animal abuse and neglect. Rolling chairs, which were introduced in 1876 and in continuous use since 1887, have been a boardwalk fixture to this day. While powered carts appeared in the 1960s, the original and most common were made of wicker. The wicker canopied chairs-on-wheels are manually pushed the length of the boardwalk by attendants, much like a Rickshaw. The Absecon Lighthouse is a coastal lighthouse located in the South Inlet section of Atlantic City overlooking Absecon Inlet. [149] It is the tallest lighthouse in the state of New Jersey and is the third tallest masonry lighthouse in the United States. Construction began in 1854, with the light first lit on January 15, 1857. [28] The lighthouse was deactivated in 1933 and although the light still shines every night, it is no longer an active navigational aid. [150] Gardner’s Basin, which is home to the Atlantic City Aquarium as well as small shops and restaurants, is located a short distance north of Absecon Light. Since 2003, Atlantic City has hosted Thunder over the Boardwalk, an annual airshow over the boardwalk. The yearly event, a joint venture between the New Jersey Air National Guard’s 177th Fighter Wing along with several casinos, attracts over 750,000 visitors each year. While located 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Atlantic City in Margate City, Lucy the Elephant has become almost an icon for the Atlantic City area. Lucy is a six-story elephant-shaped example of novelty architecture, constructed of wood and tin sheeting in 1882 by James V. Lafferty in an effort to sell real estate and attract tourism. Over the years, Lucy had served as a restaurant, business office, cottage, and tavern (the last closed by Prohibition). Lucy had fallen into disrepair by the 1960s and was scheduled for demolition. The structure was moved and refurbished as a result of a “Save Lucy” campaign in 1970 and received designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1976, and is open as a museum. Atlantic City is the home of the Miss America competition, however it was moved to Las Vegas for seven years before returning. The Miss America competition originated on September 7, 1921, as a two-day beauty contest, and it included state contestants as well as women from various cities around the country. The event that year was called the “Atlantic City Pageant”, and the winner of the grand prize, Margaret Gorman, took home the 3-foot Golden Mermaid trophy. Gorman was not called “Miss America” until 1922, when she re-entered the pageant and lost to Mary Campbell. [154] The pageant was initiated to extend the tourist season after the Labor Day weekend. [44] The pageant has been nationally televised since 1954. It peaked in the early 1960s, when it was repeatedly the highest-rated program on American television. It was seen as a symbol of the United States, with Miss America often being referred to as the female equivalent of the President. The pageant’s longtime emcee, Bert Parks, hosted the event from 1955 to 1979. At the Atlantic City Convention Center, there is a 400-pound (180 kg) interactive statue of Parks holding a crown. When a visitor puts their head inside the crown, sensors activate a recorded playback of his There She Is… Line through speakers hidden behind nearby bushes. An LGBT event known as the “Miss’d America Pageant” is held annually. Originally started in 1994 as a fundraiser for local LGBT charities, the event features drag queens on the runway in a similar manner to the Miss America pageant. Since 2010, Boardwalk Empire, an American television series from cable network HBO set in Atlantic City during the Prohibition era, has cast a new light on the city. Starring Steve Buscemi, the show was adapted from a chapter about historical criminal kingpin Enoch “Nucky” Johnson (who is renamed “Enoch Thompson” in the show) in Nelson Johnson’s book, Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times, and Corruption of Atlantic City. The series was filmed in New York City at various locations that captured Atlantic City’s period architecture and on a set built to resemble the Atlantic City boardwalk in the 1920s. Around the same time of the September 2010 premiere of the show, the Press of Atlantic City created Boss of the Boardwalk, a 45-minute documentary which premiered on August 21, 2010, on NBC TV-40 and aired six additional times in the following weeks. After the premiere of Boardwalk Empire, interest in Roaring Twenties-era Atlantic City has grown. In October 2010, a plan was revealed to renovate the ailing Resorts Casino Hotel into a Roaring Twenties theme. The re-branding was proposed by current owner Dennis Gomes, and was initiated in December 2010 when he took over the casino. The changes accentuate the resort’s existing art deco design, as well as presenting new 20s-era uniforms for employees and music from the time period. The casino also introduced drinks and shows reminiscent of the period. [160] The actual building where he lived, The Ritz-Carlton, offer tours. In 2011, Academy Bus began a trolley tour called “Nucky’s Way”, a tour bus service that features actors portraying Nucky, as well as other characters, as it loops around the city. Nucky’s Way is the second trolley tour to capitalize off of Boardwalk Empire, after The Great American Trolley company started a weekly tour of Atlantic City with a Roaring Twenties theme in early June 2011. On August 1, 2011, a façade modeled after the set of Boardwalk Empire was unveiled on the boardwalk in front of an empty lot at the former site of the Trump World’s Fair resort. The façade of storefronts, which consists of vinyl tacked onto three large sections of plywood, was the brainchild of longtime area radio host Pinky Kravitz, who was also a columnist for The Press of Atlantic City and host of WMGM-TV Presents Pinky on NBC40. In 2014, it was announced that Atlantic City would host two major beach concerts. The two headliners were Blake Shelton, which took place on July 31, 2015, and Lady Antebellum, which took place on August 3, 2014. On June 22, 2015, it was announced that Maroon 5 with special guest Nick Jonas and Matt McAndrew would headline on August 16, 2015. A few weeks later, it was announced that Rascal Flatts would play the second major beach concert of the summer season on August 20, 2015, with special guest Ashley Monroe. This concert would be part of their Riot Tour. Both concerts charged admission. Augustine College Preparatory School. Atlantic City Boardwalk Bullies. Atlantic City High School. On November 16, 2006, Hal Handel, CEO of Greenwood Racing, announced that the Atlantic City Race Course in Hamilton Township would increase live racing dates from four days per year, to up to 20 days per year. The ShopRite LPGA Classic is an LPGA Tour women’s golf tournament held near Atlantic City since it started in 1986. Since February 2, 1887, the city of Atlantic City has seen 2,538 (as of September 2018) professional boxing fight programs, [173] the first one being one with a main event fight between Willie Clark, 3-0-3, and debuting Horace Leeds, won by Clark on points over four rounds. [174] During the 1980s, professional boxing activity boomed in Atlantic City, at times rivaling Las Vegas, Nevada, in staging major boxing fights. Fighters who fought in Atlantic City at that era include Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns, Wilfredo Gomez, Jeff Chandler, Larry Holmes, George Foreman, Mike Tyson and others. Fights included The Brawl For it All, Tyson versus Holmes, Tyson versus Michael Spinks, and Roberto Durán versus Iran Barkley. Many boxing matches were held at Donald Trump’s Trump Plaza, promoted either by Bob Arum or Don King. Atlantic City is one of five municipalities in the state-and the only one outside of Cape May County-that offer free public access to oceanfront beaches monitored by lifeguards, joining Wildwood, North Wildwood, Wildwood Crest and Upper Township’s Strathmere section. Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. Source: 2007 FBI UCR Data. Further information: Mayors of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Atlantic City is governed within the Faulkner Act (formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law) under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government (Plan D), implemented by direct petition effective as of July 1, 1982. [10][176] The city is one of 71 municipalities (of the 565) statewide governed under this form. [177] The governing body of Atlantic City is the Mayor and the City Council, all elected on a partisan basis to serve four-year terms of office as part of the November general election. The council is comprised of nine members, who are elected on a staggered basis, with one member from each of six wards and three serving at-large. The six ward seats are up for election together and the mayoral seat and the council at-large seats are up for vote together two years later. The City Council exercises the legislative power of the municipality for the purpose of holding Council meetings to introduce ordinances and resolutions to regulate City government. [178] Former Mayor Bob Levy created the Atlantic City Ethics Board in 2007, but the Board was dissolved two years later by vote of the Atlantic City Council. As of 2020, the Acting Mayor is Marty Small Sr. [179] who succeeded Frank M. Following his resignation on October 3, 2019. [180] Small will serve as mayor for an unexpired term ending on December 31, 2021. [181] Members of the City Council are Council President George Tibbitt (D, 2021; At-Large), Council Vice President Moisse “Mo” Delgado (D, 2021; At-Large), LaToya Dunston (D, 2023; Second Ward – appointed to serve an unexpired term), Jeffree Fauntleroy II (D, 2021; At-Large), Jesse O. Kurtz (Republican Party, 2023; 6th Ward), MD Hossain Morshed (D, 2023; 4th Ward), Aaron “Sporty” Randolph (D, 2023; 1st Ward), Kaleem Shabazz (D, 2023; 3rd Ward) and Muhammad “Anjum” Zia (D, 2023; 5th Ward). [7][182][183][184][185]. In May 2020, voters rejected by a 3-1 margin a referendum that would have changed the city to a council-manager form of government which would have reduced the size of the city council and shifted responsibility for day-to-day operation from an elected mayor to an appointed city manager. In December 2019, LaToya Dunston was selected from a list of three candidates nominated by the Democratic municipal committee to serve the remainder of the term of the Second Ward seat that had been held by Marty Small until he stepped down when he was appointed as mayor. [187] In January 2020, Dunston was appointed to fill the Second Ward seat expiring in December 2023 that Small had won in November 2019 but declined to fill; Dunston will serve on an interim basis until the November 2020 general election, when voters will select a candidate to serve the balance of the term of office. Following questions about false claims he had made about his military record, Mayor Bob Levy left City Hall in September 2007 in a city-owned vehicle for an unknown destination. After a 13-day absence, his lawyer revealed that Levy was in Carrier Clinic, a rehabilitation hospital. [189] Levy resigned in October 2007 and then-Council President William Marsh assumed the office of Mayor[190] and served six weeks until an interim mayor was named. Atlantic City is located in the 2nd Congressional district[191] and is part of New Jersey’s 2nd state legislative district. For the 116th United States Congress, New Jersey’s Second Congressional District is represented by Jeff Van Drew (R, Dennis Township). [194] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2021)[195] and Bob Menendez (Paramus, term ends 2025). Brown (R, Ventnor City) and in the General Assembly by Vince Mazzeo (D, Northfield) and John Armato (D, Buena Vista Township). Atlantic County is governed by a directly elected county executive and a nine-member Board of Chosen Freeholders, responsible for legislation. The executive serves a four-year term and the freeholders are elected to staggered three-year terms, of which four are elected from the county on an at-large basis and five of the freeholders represent equally populated districts. [200][201] As of 2018, Atlantic County’s Executive is Republican Dennis Levinson, whose term of office ends December 31, 2019. [202] Members of the Board of Chosen Freeholders are Chairman Frank D. Formica, Freeholder At-Large (R, 2018, Margate City)[203] Vice Chairwoman Maureen Kern, Freeholder District 2, including Atlantic City (part), Egg Harbor Township (part), Linwood, Longport, Margate City, Northfield, Somers Point and Ventnor City (R, 2018, Somers Point), [204] Ashley R. Bennett, Freeholder District 3, including Egg Harbor Township (part) and Hamilton Township (part) (D, 2020, Egg Harbor Township), [205] James A. Bertino, Freeholder District 5, including Buena, Buena Vista Township, Corbin City, Egg Harbor City, Estell Manor, Folsom, Hamilton Township (part), Hammonton, Mullica Township and Weymouth Township (R, 2018, Hammonton), [206] Ernest D. Coursey, Freeholder District 1, including Atlantic City (part), Egg Harbor Township (part) and Pleasantville (D, 2019, Atlantic City), [207] Richard R. Dase, Freeholder District 4, including Absecon, Brigantine, Galloway Township and Port Republic (R, 2019, Galloway Township), [208] Caren L. Fitzpatrick, Freeholder At-Large (D, 2020, Linwood), [209] Amy L. Gatto, Freeholder At-Large (R, 2019, Mays Landing in Hamilton Township)[210] and John W. Risley, Freeholder At-Large (R, 2020, Egg Harbor Township)[211][200][212] Atlantic County’s constitutional officers are County Clerk Edward P. McGettigan (D, 2021; Linwood), [213] [214] Sheriff Eric Scheffler (D, 2021, Northfield)[215][216] and Surrogate James Curcio (R, 2020, Hammonton). As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 20,001 registered voters in Atlantic City, of which 12,063 60.3% vs. 30.5% countywide were registered as Democrats, 1,542 7.7% vs. 25.2% were registered as Republicans and 6,392 32.0% vs. 44.3% were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 4 voters registered to other parties. [220] Among the city’s 2010 Census population, 50.6% vs. 58.8% in Atlantic County were registered to vote, including 67.0% of those ages 18 and over vs. In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 9,948 votes 86.6% vs. 57.9% countywide, ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 1,548 votes 13.5% vs. 41.1% and other candidates with 49 votes 0.4% vs. 0.9%, among the 11,489 ballots cast by the city’s 21,477 registered voters, for a turnout of 53.5% vs. 65.8% in Atlantic County. [222][223] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 10,975 votes 82.1% vs. 56.5% countywide, ahead of Republican John McCain with 2,175 votes 16.3% vs. 41.6% and other candidates with 82 votes 0.6% vs. 1.1%, among the 13,370 ballots cast by the city’s 26,030 registered voters, for a turnout of 51.4% vs. 68.1% in Atlantic County. [224] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 8,487 votes 74.5% vs. 52.0% countywide, ahead of Republican George W. Bush with 2,687 votes 23.6% vs. 46.2% and other candidates with 96 votes 0.8% vs. 0.8%, among the 11,389 ballots cast by the city’s 23,310 registered voters, for a turnout of 48.9% vs. 69.8% in the whole county. In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 4,293 ballots cast 52.6% vs. 34.9% countywide, ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 2,897 votes 35.5% vs. 60.0% and other candidates with 63 votes 0.8% vs. 1.3%, among the 8,155 ballots cast by the city’s 23,049 registered voters, yielding a 35.4% turnout vs. 41.5% in the county. [226][227] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 4,988 ballots cast 69.9% vs. 44.5% countywide, ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 1,578 votes 22.1% vs. 47.7%, Independent Chris Daggett with 157 votes 2.2% vs. 4.8% and other candidates with 99 votes 1.4% vs. 1.2%, among the 7,141 ballots cast by the city’s 22,585 registered voters, yielding a 31.6% turnout vs. 44.9% in the county. Main article: New Jersey Casino Control Commission. The New Jersey Casino Control Commission is a New Jersey state governmental agency that was founded in 1977 as the state’s Gaming Control Board, responsible for administering the Casino Control Act and its regulations to assure public trust and confidence in the credibility and integrity of the casino industry and casino operations in Atlantic City. Casinos operate under licenses granted by the commission. The commission is headquartered in the Arcade Building at Tennessee Avenue and Boardwalk in Atlantic City. Main article: New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement. Main article: Casino Reinvestment Development Authority. The CRDA was founded in 1984 and is responsible for directing the spending of casino reinvestment funds in public and private projects to benefit Atlantic City and other areas of the state. The Convention & Visitors Authority (ACCVA) was in charge of advertising and marketing for the city as well as promoting economic growth through convention and leisure tourism development. The ACCVA managed the Boardwalk Hall and Atlantic City Convention Center, as well as the Boardwalk Welcome Center inside Boardwalk Hall and a welcome center on the Atlantic City Expressway. In 2011, the ACCVA was absorbed into the CRDA as part of the state takeover that created the tourism district. It carried out various activities to improve the city’s business community, including street cleaning and promotional efforts. In 2011, the SID was absorbed by the CRDA; the former SID boundaries would be expanded to the include all areas in the newly formed tourism district. Under the new structure, established by state legislation, the CRDA assumed responsibility for the staff, equipment and programs of the SID. The new SID division includes a SID committee made up of CRDA board members and an advisory council consisting of the current trustees and others. Atlantic City Fire Department (ACFD). April 4, 1904[233]. The Atlantic City Fire Department (ACFD) provides fire protection and first responder emergency medical services to the city. The ACFD operates out of six fire stations, located throughout the city in one battalion, under the command of a Battalion Chief, who in-turn reports to an on-duty Deputy Chief, or Tour Commander each shift. Station 1; Atlantic Ave & Maryland Ave. Engine 1, Tower Ladder 1, Battalion Chief 1, Haz-Mat 1. Station 2; Baltic Ave & North Indiana Ave. Engine 2, Rescue 1, Collapse Rescue Unit, Fire Boats 1&2. Station 3; North Indiana Ave & Grant Ave. Engine 3, Ladder 3 (Tiller). Station 4; Atlantic Ave & South Carolina Ave. Engine 4, Ladder 2 (Tiller), Deputy Chief 1. Station 5; Bader Field. Engine 5, Air Cascade Unit 1. Station 6; Atlantic Ave & South Annapolis Ave. Engine 6, Engine 7. Main article: Atlantic City Police Department. The city is protected by the Atlantic City Police Department, which handles 150,000 calls per year. The Chief of Police is Henry White. The Atlantic City School District serves students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grades. [238] As of the 2017-18 school year, the eleven schools in the district had a combined enrollment of 7,157 students and a faculty of 614.9 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis) for a student-teacher ratio of 11.6:1. [239] Schools in the district (with 2017-18 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[240]) are Venice Park School[241] (75 students in PreK), Brighton Avenue School[242] (346 students; in grades PreK-5), Chelsea Heights School[243] (367; PreK-8), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School Complex[244] (599; PreK-8), New York Avenue School[245] (605; PreK-8), Pennsylvania Avenue School[246] (559; PreK-8), Richmond Avenue School[247] (715; PreK-8), Sovereign Avenue School[248] (736; PreK-8), Texas Avenue School[249] (560; K-8), Uptown School Complex[250] (572; PreK-8) and Atlantic City High School[251] (1,882; 9-12). [252][253] Pennsylvania Avenue School opened for the 2012-13 school year, with most students shifting from New Jersey Avenue School, which had been one of the district’s oldest and most rundown schools. Students from Brigantine, Longport, Margate City and Ventnor City attend Atlantic City High School as part of sending/receiving relationships with the respective school districts. City public school students are also eligible to attend the Atlantic County Institute of Technology in the Mays Landing section of Hamilton Township[257] or the Charter-Tech High School for the Performing Arts, located in Somers Point. Oceanside Charter School, which offered pre-Kindergarten through eighth grade, was founded in 1999 and closed in June 2013 when its charter wasn’t renewed by the New Jersey Department of Education. Founded in 1908, Our Lady Star of the Sea Regional School is a Catholic elementary school, operated under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Camden. Nearby college campuses include those of Atlantic Cape Community College and Stockton University, the latter of which offers classes and resources in the city such as the Carnegie Library Center. See also: Newspapers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Press of Atlantic City. Radio stations in Atlantic City, Cape May, and the southern Jersey Shore. WEHA 88.7 FM – Gospel. WAYV 95.1 FM – Top 40. WTTH 96.1 FM – Urban AC. WFPG 96.9 FM – AC (Lite Rock 96.9). WENJ 97.3 FM – Sports. WTKU 98.3 FM – Classic hits (Kool 98.3). WZBZ 99.3 FM – Rhythmic (The Buzz). WZXL 100.7 FM – Rock (The Rock Station). WLRB 102.7 FM – Contemporary Christian (K-Love). WMGM 103.7 FM – Active rock (WMGM Rocks). WSJO 104.9 FM – Hot AC (Sojo 104.9). WPUR 107.3 FM – Country (Cat Country 107.3). See also: Media of Philadelphia § Television stations. Atlantic City is part of the Philadelphia television market. There, six stations licensed in the area. WACP Channel 4 Atlantic City (Independent). WMGM-LP Channel 7 Atlantic City (Silent). WMGM-TV Channel 40 Wildwood (Justice Network). W45CP-D Channel 45 Atlantic City (Daystar). W48DP-D Channel 48 Atlantic City (EICB). Junction of the Atlantic City Expressway and the Atlantic City-Brigantine Connector in Atlantic City. As of May 2010, the city had a total of 103.67 miles (166.84 km) of roadways, of which 88.26 miles (142.04 km) were maintained by the municipality, 1.29 miles (2.08 km) by Atlantic County, 5.32 miles (8.56 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 8.80 miles (14.16 km) by the South Jersey Transportation Authority. The three roadways into Atlantic City are the Black Horse Pike/Harding Highway (US 322/40 via the Albany Avenue drawbridge), White Horse Pike (US 30), and the Atlantic City Expressway (including the Brigantine Connector). Atlantic City is roughly 132 miles (212 km) south of New York City by road (via the Garden State Parkway) and 55 miles (89 km) southeast of Philadelphia. Atlantic City Rail Terminal. 29 on a casino shuttle run. NJ Transit #2514 on the 505. Atlantic City is connected to other cities in several ways. NJ Transit’s Atlantic City Rail Terminal[264] at the Atlantic City Convention Center provides service from 30th Street Station in Philadelphia through several smaller South Jersey communities via the Atlantic City Line. On June 20, 2006, the board of NJ Transit approved a three-year trial of express train service between New York Penn Station and the Atlantic City Rail Terminal. The line, known as ACES (Atlantic City Express Service), ran from February 2009 to March 2012. The approximate travel time was? 2 1? 2 hours, with a stop at Newark’s Penn Station, and was part of the casinos’ multimillion-dollar investments in Atlantic City. Most of the funding for the transit line was provided by Harrah’s Entertainment (owners of both Harrah’s Atlantic City and Caesars Atlantic City) and the Borgata. The Atlantic City Bus Terminal is the home to local, intrastate and interstate bus companies including NJ Transit, Academy and Greyhound bus lines. The Greyhound Lucky Streak Express offers service to Atlantic City from New York City, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D. [267] In addition to stopping at the Atlantic City Bus Terminal, Greyhound buses stop at various casinos in Atlantic City. Martz Trailways provides bus service to various casinos in Atlantic City from Wilkes-Barre, Scranton, and White Haven in Pennsylvania. [268] Klein Transportation provides bus service to various casinos in Atlantic City from Shillington, Douglassville, Royersford, and Audubon in Pennsylvania. Within the city, public transportation is provided by NJ Transit along 13 routes, including service between the city and the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown Manhattan on the 319 route, and service to and from Atlantic City on routes 501 (to Brigantine Beach), 502 (to Atlantic Cape Community College), 504 (to Ventnor Plaza), 505 (to Longport), 507 (to Ocean City), 508 (to the Hamilton Mall), 509 (to Ocean City), 551 (to Philadelphia), 552 (to Cape May), 553 (to Upper Deerfield Township), 554 (to the Lindenwold PATCO station) and 559 (to Lakewood Township). The Atlantic City Jitney Association (ACJA) offers service on four fixed-route lines and on shuttles to and from the rail terminal. Commercial airlines serve Atlantic City via Atlantic City International Airport, located 9 miles (14 km) northwest of the city in Egg Harbor Township. Many travelers also fly into Philadelphia International Airport, Trenton-Mercer Airport, or Newark Liberty International Airport, where there are wider selections of carriers from which to choose. The historic downtown Bader Field airport is now permanently closed and plans are in the works to redevelop the land. Atlantic City International Airport is a focus city for Spirit Airlines. The airport is also served by various scheduled chartered flight companies. The AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center City Campus. The AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center is a health system based in Atlantic City. Founded in 1898, it includes two hospitals; the Atlantic City Campus and the Mainland Campus in Pomona, New Jersey. It has Atlantic City’s only cancer institute, heart institute, and neonatal intensive care unit. South Jersey Industries provides natural gas to the city under the South Jersey Gas division. Marina Energy and its subsidiary, Energenic, a joint business venture with a long-time business partner, operate two thermal power stations in the city. The Marina Thermal Plant serves the Borgata while a second plant serves the Resorts Hotel and Casino. [274] Another thermal plant is the Midtown Thermal Control Center on Atlantic and Ohio Avenues built by Conectiv, which opened in 1997 and provides chilled water for hotels and other facilities along the Boardwalk. Electrical power in Atlantic City as well as the surrounding area is primarily served by Atlantic City Electric, which was incorporated in 1924 and provides power from the Beesley’s Point Generating Station in Upper Township, as well as other locations. Jersey-Atlantic is the first coastal wind farm in the United States and a tourist attraction[277]. The Jersey-Atlantic Wind Farm, opened in 2005, is the first onshore coastal wind farm in the United States. [278] In October 2010, North American Offshore Wind Conference was held in the city and included tours of the facility and potential sites for further development. [279] In February 2011, the state passed legislation permitting the construction of windmills for electricity along pre-existing piers, such as the Steel Pier. [280][281] The first phase of the Atlantic Wind Connection, a planned electrical transmission backbone along the Jersey Shore was planned to be operational in 2013. Further information: Category:Films shot in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Atlantic City has been shown in several other aspects of pop culture. Films such as The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), [282] Atlantic City, [283] The Godfather Part III, [284] Rounders[285] and Snake Eyes[286] have featured the city, as have television programs such as The Simpsons, [287] How I Met Your Mother, [288] and Boardwalk Empire. See also: Category:People from Atlantic City, New Jersey. People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Atlantic City include. Hakeem Abdul-Shaheed (born 1959), convicted drug dealer and organized crime leader. Jack Abramoff (born 1958), former lobbyist who was embroiled in high-profile political scandals. Abramoff was born in Atlantic City and lived there until age 10. Robert Agnew (born 1953), professor of sociology at Emory University and president of the American Society of Criminology. Barry Beckham (born 1944), playwright and novelist. Benjamin Burnley (born 1978), musician, best known as lead vocalist, rhythm guitarist and primary songwriter for band Breaking Benjamin. Greg Buttle (born 1954), linebacker who played in the NFL for the New York Jets. Buzby (born 1956), former United States Navy rear admiral who serves as Administrator of the United States Maritime Administration. Vera Coking, property owner who prevailed in her battle to oppose Donald Trump’s efforts to acquire her boarding house using eminent domain. Jack Collins (born 1943), Speaker of the New Jersey General Assembly from 1996 until 2002, making him the longest-serving speaker in Assembly history. Stuart Dischell (born 1954), poet and professor of English at University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Bruce Ditmas (born 1946), jazz drummer and percussionist.