Month: September 2022

Natasha Denona My Dream Collection Lets Try It

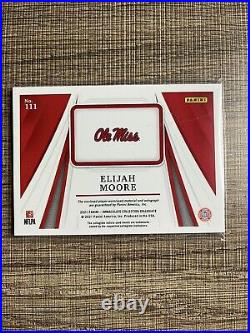

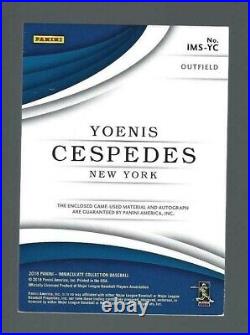

2021 Panini Immaculate Rookie Team Slogans Hotty Toddy Auto 9/10 Elijah Moore

2021 Panini Immaculate Rookie Team Slogans “Hotty Toddy” Auto 9/10 Elijah Moore. This item is in the category “Sports Mem, Cards & Fan Shop\Sports Trading Cards\Trading Card Singles”. The seller is “hollabackdeals” and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States.

- Graded: No

- Type: Sports Trading Card

- Autographed: Yes

- Sport: Football

- League: National Football League (NFL)

- Set: 2021 Panini Immaculate Collection

- Card Condition: Mint

- Manufacturer: Panini

- Features: Rookie

- Player/Athlete: Elijah Moore

- Team: New York Jets

- Season: 2021

Old School Jampack Baseball Card Box September 2022

Full Baseball Collection Updated Autographs Baseballs Jerseys

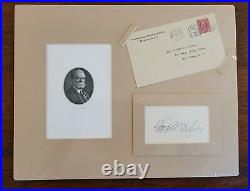

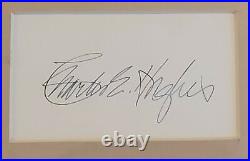

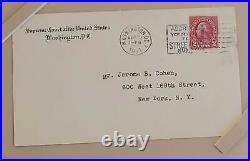

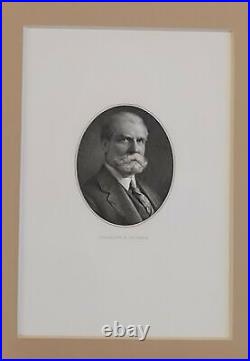

Supreme Court Autograph 1931 Charles E. Hughes + Envelope + Matted Signed

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL AUTOGRAPH BEAUTIFULLY MATTED 11X14 INCHES AND PROTECTED IN PLASTIC OF SUPREME COURT JJSTICE OF THE UNITED STATES CHARLES E. HUGHES WHICH COME WITH THE ORIGINAL MAILING ENVELOPE FROM 1931 AND A PORTRAIT OF CHARLES E. Charles Evans Hughes Sr. Was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. Nicknamed the “roving Justices, ” new Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts sometimes joined the “four horsemen”-Justices George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, James C. McReynolds, and Willis Van Devanter–sometimes joined three Judges more willing to accept laws however meddlesome. These three were Louis D. Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Oliver Wendell Holmes until he retired in 1932. Cardozo succeeded him, and often voted with Brandeis and Stone. In 1925, while the Court was deciding the Benjamin Gitlow case, Minnesota legislators were passing a new statute. It provided that a court order could silence, as “public nuisances, ” periodicals that published “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory” material. “Unfortunately we are both former editors of a local scandal sheet, a distinction we regret, ” conceded J. Near and his partner in the first issue of the Saturday Press, but they promised to fight crime in Minneapolis. They called the police chief a “cuddler of criminals” who protected rat gamblers. They abused the county attorney, who sued Near; the state’s highest court ordered the paper suppressed. Citing the Schenck and Gitlow decisions, Near’s lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court, which struck down the state law in 1931. For four dissenters, Pierce Butler quoted with evident distaste Near’s outbursts at “snake-faced” Jewish gangsters; peace and order need legal protection from such publishers, Butler insisted. For the majority, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes analyzed this “unusual, if not unique” law. If anyone published something “scandalous” a Minnesota court might close his paper permanently for damaging public morals. But charges of corruption in office always make public scandals, Hughes pointed out. Anyone defamed in print may sue for libel, he added emphatically. However disgusting Near’s words, said Hughes, the words of the Constitution controlled the decision, and they demand a free press without censorship. Criticism may offend public officials, it may even remove them from office; but trashy or trenchant, the press may not be suppressed by law. How citizens use liberty has confronted the Justices again and again, in cases of violence as well as scandal. Alabama militia had machine guns on the courthouse roof, said newspaper reports from Scottsboro; mobs had a band playing “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight”; and amid the clamor, nine black youths waited behind bars for trial on charges of raping two white women. Across the Alabama line, white and black hoboes on board got into a fight; some jumped and some were thrown from the train. Alerted by telephone, a sheriff’s posse stopped the train, arrested the nine Negroes still on it, and took them to jail in the Jackson County seat, Scottsboro. Then Victoria Price claimed they had raped her and Ruby Bates. Doctors found no proof of this story, but a frenzied crowd gathered swiftly. Ten thousand people, many armed, were there a week later when the nine went on trial. Because state law provided a death penalty, it required the court to appoint one or two defense lawyers. At the arraignment, the judge told all seven members of the county bar to serve. In three trials, completed in three days, jurors found eight defendants guilty; they could not agree on Roy Wright, one of the youngest. The eight were sentenced to death. Of these nine, the oldest might have reached 21; one was crippled, one nearly blind; each signed his name by “X”-his mark. All swore they were innocent. On appeal, Alabama’s highest court ordered a new hearing for one of the nine, Eugene Williams; but it upheld the other proceedings. When a petition in the name of Ozie Powell reached the Supreme Court, seven Justices agreed that no lawyer had helped the defendants at the trials. Justice George Sutherland wrote the Court’s opinion. Facing a possible death sentence, unable to hire a lawyer, too young or ignorant or dull to defend himself-such a defendant has a constitutional right to counsel, and his counsel must fight for him, Sutherland said. Sent back for retrial, the cases went on. Alabama reached the Supreme Court in 1935; Chief Justice Hughes ruled that because qualified Negroes did not serve on jury duty in those counties, the trials had been unconstitutional. We still have the right to secede! Retorted one southern official. Again the prisoners stood trial. Alabama dropped rape charges against some; others were conflicted but later paroled; one escaped. The Supreme Court’s rulings stood-if a defendant lacks a lawyer and a fairly chosen jury, the Constitution can help him. The Scottsboro Boys in 1937. And the Constitution forbids any state’s prosecuting attorneys to use evidence they know is false; the Court announced this in 1935, when Tom Mooney had spent nearly 20 years behind the bars of a California prison. To rally support for a stronger Army and Navy, San Franciscans had organized a huge parade for “Preparedness Day, ” July 22, 1916. As the marchers set out, a bomb exploded: 10 victims died, 40 were injured. Mooney, known as a friend of anarchists and a labor radical, was convicted of first-degree murder; soon it appeared that the chief witness against him had lied under oath. President Wilson persuaded the Governor of California to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. For years labor called Mooney a martyr to injustice. Finally Mooney’s lawyers applied to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, and won a new ruling-if a state uses perjured witnesses, knowing that they lie, it violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process of law; it must provide ways to set aside such tainted convictions. The case went back to the state. In 1939 Governor Culbert Olson granted Mooney a pardon; free, he was almost forgotten. When the stock market collapsed in 1929 and the American economy headed toward ruin, President Hoover had called for emergency measures. The states tried to cope with the general disaster. Before long, cases on their new laws began to reach the Supreme Court. Roosevelt won the 1932 Presidential election, and by June 1933, Congress had passed 15 major laws for national remedies. Grocer Leo Nebbia, who violated the New York Milk Control Board’s order to fix prices of milk in order to stabilize the market. Agitator and Martyr for Labor, Tom Mooney leaves San Quentin in 1939. Almost 20,000,000 people depended on federal relief by 1934, when the Supreme Court decided the case of Leo Nebbia. Justice Owen Roberts wrote the majority opinion, upholding the New York law; he went beyond the 1887 decision in the Granger cases to declare that a state may regulate any business whatever when the public good requires it. The “four horsemen” dissented; but Roosevelt’s New Dealers began to hope their economic program might win the Supreme Court’s approval after all. Considering a New Deal law for the first time, in January 1935, the Court held that one part of the National Industrial Recovery Act gave the President too much lawmaking power. The Court did sustain the policy of reducing the dollar’s value in gold. But a five-to-four decision in May made a railroad pension law unconstitutional. Then all nine Justices vetoed a law to relieve farm debtors, and killed the National Recovery Administration; FDR denounced their “horse-and-buggy” definition of interstate commerce. While the Court moved into its splendid new building, criticism of its decisions grew sharper and angrier. The whole federal judiciary came under attack as district courts issued-over a two-year period-some 1,600 injunctions to keep Acts of Congress from being enforced. But the Court seemed to ignore the clamor. Farming lay outside Congressional power, said six Justices in 1936; they called the Agricultural Adjustment Act invalid for dealing with state problems. Brandeis and Cardozo joined Stone in a scathing dissent: Courts are not the only agency. That must be assumed to have capacity to govern. But two decisions that followed denied power to both the federal and the state governments. In a law to strengthen the chaotic soft-coal industry and help the almost starving miners, Congress had dealt with prices in one section, with working conditions and wages in another. If the courts held one section invalid, the other might survive. When a test case came up, seven coal-mining states urged the Court to uphold the Act, but five Justices called the whole law unconstitutional for trying to cure “local evils”-state problems. Then they threw out a New York law that set minimum wages for women and children; they said states could not regulate matters of individual liberty. By forbidding Congress and the states to act, Justice Harlan F. Stone confided bitterly to his sister, the Court had apparently tied Uncle Sam up in a hard knot. Tortured and whipped by deputy sheriffs, three men confessed to murder; in 1936 the Supreme Court found that their state, Mississippi, had denied them due process of law. That November Roosevelt won reelection by a margin of ten million votes; Democrats won more than three-fourths of the seats in Congress. The people had spoken. Yet the laws their representatives passed might stand or fall by five or six votes in the Supreme Court. Roosevelt, aware that Congress had changed the number of Justices six times since 1789, sent a plan for court reform to the Senate on February 5, 1937. Emphasizing the limited vision of “older men, ” Roosevelt asked Congress for power to name an additional Justice when one aged 70 did not resign, until the Court should have 15 members. Six were already over 70; Louis D. Roosevelt said the Court needed help to keep up with its work. Even staunch New Dealers boggled at this plan; it incurred criticism as sharp as any the Court had ever provoked. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes calmly pointed out that the Court was keeping up with its work. And in angry editorials and thousands of letters to Congress the public protested the very idea of “packing” the Court. This 1937 steel strike occured in Pittsburgh following the Supreme Court’s decision to order union employees fired from their jobs at Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation reinstated. President Roosevelt’s attempt to add more Justices to the Court in 1937 met with defeat. Before the President revealed his plan, five Justices had already voted to sustain a state minimum-wage law in a case from Washington; on March 29, the Court announced that the law was constitutional. On April 12, Chief Justice Hughes read the majority opinion in National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation. It upheld the Wagner Act, the first federal law to regulate disputes between capital and labor. Hughes gave interstate commerce a definition broader than the Jones & Laughlin domain-mines in Minnesota, quarries in West Virginia, steamships on the Great Lakes. Although the case turned on a union dispute at one plant in Pennsylvania, he said, a company-wide dispute would paralyze interstate commerce. Congress could prevent such evils and protect union rights. Under these two rulings, Congress and the states were free to exercise powers the Court had denied just a year before. Stubbornly the “four horsemen” dissented. But Willis Van Devanter announced that he would retire. By autumn the fight over the Court was a thing of the past. As Lincoln said in 1861, the people would rule themselves; they would decide vital questions of national policy. But, as firmly as Lincoln himself, they disclaimed any assault upon the Court. In one of the Supreme Court’s greatest crises, the people chose to sustain its power and dignity. Decisions changed dramatically in the “constitutional revolutions” of 1937. So did the Court when President Roosevelt made appointments at last. In 1937 he named Senator Hugo L. Black; in 1938, Solicitor General Stanley Reed; in 1939, Felix Frankfurter and William O. New problems tested the Court as it was defining civil liberties. Danger from abroad made the case for patriotism and freedom in America more urgent; in the “blood purge” of 1934, Adolf Hitler had announced, I became the supreme judge of the German people. Under God’s law, the Commandments in the Book of Exodus, members of Jehovah’s Witnesses refuse to salute a flag. When Lillian and William Gobitas (misspelled “Gobitis” in the record), aged 12 and 10 in 1935, refused to join classmates in saluting the Stars and Stripes, the Board of Education in Minersville, Pennsylvania, decided to expel them for insubordination. With help from other Jehovah’s Witnesses and the American Civil Liberties Union, their father sought relief in the federal courts. The district court and the circuit court of appeals granted it. In 1940 the school board turned to the Supreme Court. Considering the right of local authorities to settle local problems, eight Justices voted to uphold the school board’s secular regulation. Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote the majority opinion. He told Justice Stone that his private idea “of liberty and toleration and good sense” favored the Gobitas family, but he believed that judges should defer to the actions of the people’s elected representatives. Hitler’s armies had stabbed into France when Frankfurter announced the Court’s ruling on June 3, 1940; Stone read his dissent with obvious emotion, insisting that the Constitution must preserve freedom of mind and spirit. Law reviews criticized the Court for setting aside the issue of religious freedom. Jehovah’s Witnesses suffered violent attacks around the country; many states expelled children from school for not saluting the flag. In 1940, Attorney General Frank Murphy came to the bench; Senator James F. Byrnes of South Carolina, in 1941. When Hughes retired that year, Roosevelt made Harlan Fiske Stone Chief Justice and gave his seat as Associate to Attorney General Robert H. How the “new Court” would meet old problems soon became clear. Charles Evans Hughes was born and raised in New York. He was educated by his parents but matriculated at Madison College (now Colgate) when he was fourteen. He completed his undergraduate education at Brown. Hughes taught briefly before entering Columbia Law School. He scored an amazing 99 1/2 on his bar exam at the age of 22. He practiced law in New York for 20 years, though he did hold an appointment at Cornell Law School for a few years in that period. With an endorsement from Theodore Roosevelt, Hughes ran successfully for New York governor, defeating Democrat William Randolph Hearst in 1906. In 1910, Hughes accepted nomination to the High Court from President Taft. Six years later, Hughes resigned to run against Woodrow Wilson for the presidency as the nominee of the Republican and Progressive Parties. He lost by a mere 23 electoral votes. After a brief stint in private practice, Hughes was called to politics again, this time as secretary of state for Warren G. Hughes continued in this role during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge. Hughes’s nomination to be chief justice met with opposition from Democrats who viewed Hughes as too closely aligned with corporate America. Their opposition was insufficient to deny Hughes the center chair, however. Hughes authored twice as many constitutional opinions as any other member of his Court. His opinions, in the view of one commentator, were concise and admirable, placing Hughes in the pantheon of great justices. Hughes had remarkable intellectual and social gifts that made him a superb leader and administrator. He had a photographic memory that few, if any, of his colleagues could match. Yet he was generous, kind, and forebearing in an institution where egos generally come in only one size: extra large! The chief justice of the United States[1][2] is the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States and the highest-ranking officer of the U. Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U. Constitution grants plenary power to the president of the United States to nominate, and with the advice and consent of the United States Senate, appoint “Judges of the supreme Court”, who serve until they resign, retire, are impeached and convicted, or die. The existence of a chief justice is explicit in Article One, Section 3, Clause 6 which states that the chief justice shall preside on the impeachment trial of the president. The chief justice has significant influence in the selection of cases for review, presides when oral arguments are held, and leads the discussion of cases among the justices. Additionally, when the court renders an opinion, the chief justice, if in the majority, chooses who writes the court’s opinion. When deciding a case, however, the chief justice’s vote counts no more than that of any other justice. Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 designates the chief justice to preside during presidential impeachment trials in the Senate; this has occurred three times. While nowhere mandated, the presidential oath of office is by tradition typically administered by the chief justice. The chief justice serves as a spokesperson for the federal government’s judicial branch and acts as a chief administrative officer for the federal courts. The chief justice presides over the Judicial Conference and, in that capacity, appoints the director and deputy director of the Administrative Office. The chief justice is an ex officio member of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution and, by custom, is elected chancellor of the board. The current chief justice is John Roberts (since 2005). Five of the 17 chief justices-John Rutledge, Edward Douglass White, Charles Evans Hughes, Harlan Fiske Stone, and William Rehnquist-served as associate justice prior to becoming chief justice. Origin, title, and appointment. List of chief justices. The United States Constitution does not explicitly establish an office of chief justice but presupposes its existence with a single reference in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6: When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside. Nothing more is said in the Constitution regarding the office. Article III, Section 1, which authorizes the establishment of the Supreme Court, refers to all members of the court simply as “judges”. The Judiciary Act of 1789 created the distinctive titles of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1866, Salmon P. Chase assumed the title of Chief Justice of the United States, and Congress began using the new title in subsequent legislation. [2] The first person whose Supreme Court commission contained the modified title was Melville Fuller in 1888. [3] The associate justice title was not altered in 1866 and remains as originally created. The chief justice, like all federal judges, is nominated by the president and confirmed to office by the U. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution specifies that they shall hold their Offices during good Behavior. This language means that the appointments are effectively for life and that once in office, a justice’s tenure ends only when the justice dies, retires, resigns, or is removed from office through the impeachment process. Since 1789, 15 presidents have made a total of 22 official nominations to the position. [5] The practice of appointing an individual to serve as chief justice is grounded in tradition; while the Constitution mandates that there be a chief justice, it is silent on the subject of how one is chosen and by whom. There is no specific constitutional prohibition against using another method to select the chief justice from among those justices properly appointed and confirmed to the Supreme Court. Three incumbent associate justices have been nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate as chief justice: Edward Douglass White in 1910, Harlan Fiske Stone in 1941, and William Rehnquist in 1986. A fourth, Abe Fortas, was nominated to the position in 1968 but was not confirmed. As an associate justice does not have to resign his or her seat on the court in order to be nominated as chief justice, Fortas remained an associate justice. Similarly, when Associate Justice William Cushing was nominated and confirmed as chief justice in January 1796 but declined the office, he too remained on the court. John Rutledge was the first. President Washington gave him a recess appointment in 1795. However, his subsequent nomination to the office was not confirmed by the Senate, and he left office and the court. In 1930, former Associate Justice Charles Evans Hughes was confirmed as chief justice. Additionally, in December 1800, former Chief Justice John Jay was nominated and confirmed to the position a second time but ultimately declined it, opening the way for the appointment of John Marshall. Article I, Section 3 of the U. Constitution stipulates that the chief justice shall preside over the Senate trial of an impeached president of the United States. Three chief justices have presided over presidential impeachment trials: Salmon P. Chase (1868 trial of Andrew Johnson), William Rehnquist (1999 trial of Bill Clinton), and John Roberts (2020 trial of Donald Trump). All three presidents were acquitted in the Senate. Although the Constitution is silent on the matter, the chief justice would, under Senate rules adopted in 1999 prior to the Clinton trial, preside over the trial of an impeached vice president. [6][7] This rule was established to preclude the possibility of a vice president presiding over their own trial. Many of the court’s procedures and inner workings are governed by the rules of protocol based on the seniority of the justices. The chief justice always ranks first in the order of precedence-regardless of the length of the officeholder’s service (even if shorter than that of one or more associate justices). This elevated status has enabled successive chief justices to define and refine both the court’s culture and its judicial priorities. The chief justice sets the agenda for the weekly meetings where the justices review the petitions for certiorari, to decide whether to hear or deny each case. The Supreme Court agrees to hear less than one percent of the cases petitioned to it. While associate justices may append items to the weekly agenda, in practice this initial agenda-setting power of the chief justice has significant influence over the direction of the court. Nonetheless, a chief justice’s influence may be limited by circumstances and the associate justices’ understanding of legal principles; it is definitely limited by the fact that he has only a single vote of nine on the decision whether to grant or deny certiorari. Despite the chief justice’s elevated stature, his vote carries the same legal weight as the vote of each associate justice. Additionally, he has no legal authority to overrule the verdicts or interpretations of the other eight judges or tamper with them. [8] The task of assigning who shall write the opinion for the majority falls to the most senior justice in the majority. Thus, when the chief justice is in the majority, he always assigns the opinion. [10] Early in his tenure, Chief Justice John Marshall insisted upon holdings which the justices could unanimously back as a means to establish and build the court’s national prestige. In doing so, Marshall would often write the opinions himself and actively discouraged dissenting opinions. Associate Justice William Johnson eventually persuaded Marshall and the rest of the court to adopt its present practice: one justice writes an opinion for the majority, and the rest are free to write their own separate opinions or not, whether concurring or dissenting. The chief justice’s formal prerogative-when in the majority-to assign which justice will write the court’s opinion is perhaps his most influential power, [9] as this enables him to influence the historical record. [8] He may assign this task to the individual justice best able to hold together a fragile coalition, to an ideologically amenable colleague, or to himself. Opinion authors can have a large influence on the content of an opinion; two justices in the same majority, given the opportunity, might write very different majority opinions. [9] A chief justice who knows the associate justices well can therefore do much-by the simple act of selecting the justice who writes the opinion of the court-to affect the general character or tone of an opinion, which in turn can affect the interpretation of that opinion in cases before lower courts in the years to come. The chief justice chairs the conferences where cases are discussed and tentatively voted on by the justices. He normally speaks first and so has influence in framing the discussion. Although the chief justice votes first-the court votes in order of seniority-he may strategically pass in order to ensure membership in the majority if desired. [9] It is reported that. Chief Justice Warren Burger was renowned, and even vilified in some quarters, for voting strategically during conference discussions on the Supreme Court in order to control the Court’s agenda through opinion assignment. Indeed, Burger is said to have often changed votes to join the majority coalition, cast “phony votes” by voting against his preferred position, and declined to express a position at conference. The chief justice has traditionally administered the presidential oath of office to new U. This is merely custom, and is not a constitutional responsibility of the chief justice. The Constitution does not require that the presidential oath be administered by anyone in particular, simply that it be taken by the president. Law empowers any federal or state judge, as well as notaries public, to administer oaths and affirmations. The chief justice ordinarily administers the oath of office to newly appointed and confirmed associate justices, whereas the seniormost associate justice will normally swear in a new chief justice. If the chief justice is ill or incapacitated, the oath is usually administered by the seniormost member of the Supreme Court. Seven times, someone other than the chief justice of the United States administered the oath of office to the president. [13] Robert Livingston, as chancellor of the state of New York (the state’s highest ranking judicial office), administered the oath of office to George Washington at his first inauguration; there was no chief justice of the United States, nor any other federal judge prior to their appointments by President Washington in the months following his inauguration. William Cushing, an associate justice of the Supreme Court, administered Washington’s second oath of office in 1793. Calvin Coolidge’s father, a notary public, administered the oath to his son after the death of Warren Harding. [14] This, however, was contested upon Coolidge’s return to Washington, and his oath was re-administered by Judge Adolph A. District Court for the District of Columbia. [15] John Tyler and Millard Fillmore were both sworn in on the death of their predecessors by Chief Judge William Cranch of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia. Arthur and Theodore Roosevelt’s initial oaths reflected the unexpected nature of their taking office. On November 22, 1963, after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Judge Sarah T. Hughes, a federal district court judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, administered the oath of office to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson aboard the presidential airplane. Since the tenure of William Howard Taft, the office of chief justice has moved beyond just first among equals. [17] The chief justice also. Serves as the head of the federal judiciary. Serves as the head of the Judicial Conference of the United States, the chief administrative body of the United States federal courts. The Judicial Conference is empowered by the Rules Enabling Act to propose rules, which are then promulgated by the Supreme Court (subject to disapproval by Congress under the Congressional Review Act), to ensure the smooth operation of the federal courts. Major portions of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Federal Rules of Evidence have been adopted by most state legislatures and are considered canonical by American law schools. Appoints sitting federal judges to the membership of the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a “secret court” which oversees requests for surveillance warrants by federal police agencies (primarily the FBI) against suspected foreign intelligence agents inside the United States. Appoints sitting federal judges to the membership of the United States Alien Terrorist Removal Court, a special court constituted to determine whether aliens should be deported from the United States on the grounds that they are terrorists. Appoints the members of the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, a special tribunal of seven sitting federal judges responsible for selecting the venue for coordinated pretrial proceedings in situations where multiple related federal actions have been filed in different judicial districts. Serves as an ex officio member of the Board of Regents and as the chancellor of the Smithsonian Institution. Supervises the acquisition of books for the Law Library of the Library of Congress. Unlike Senators and Representatives, who are constitutionally prohibited from holding any other “office of trust or profit” of the United States or of any state while holding their congressional seats, the chief justice and the other members of the federal judiciary are not barred from serving in other positions. John Jay served as a diplomat to negotiate the Jay Treaty, Robert H. Jackson was appointed by President Truman to be the U. Prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials of leading Nazis, and Earl Warren chaired the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. [20] Currently, Clarence Thomas is the most senior associate justice. Since the Supreme Court was established in 1789, the following 17 men have served as chief justice:[21][22]. 5 years, 253 days. United States Secretary of State. John Rutledge color painting. August 12, 1795[d]. (Resigned, nomination having been rejected). Chief Justice of the. South Carolina Court of. Common Pleas and Sessions. Of the Supreme Court. 4 years, 282 days. 34 years, 152 days. 28 years, 198 days. 8 years, 143 days. 14 years, 19 days. 21 years, 269 days. Illinois State Bar Association. December 12, 1910[e]. 10 years, 151 days. 8 years, 207 days. President of the United States. 11 years, 126 days. June 27, 1941[e]. 4 years, 293 days. 7 years, 76 days. October 5, 1953[d]. 15 years, 261 days. 17 years, 95 days. United States Court of Appeals. For the District of Columbia Circuit. September 17, 1986[e]. 18 years, 342 days. 15 years, 270 days. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he was also the 36th Governor of New York, the Republican nominee for president of the United States in the 1916 presidential election, and the 44th United States Secretary of State. Born to a Welsh immigrant preacher and his wife in Glens Falls, New York, Hughes graduated from Brown University and Columbia Law School and practiced law in New York City. He won election as the Governor of New York in 1906, and implemented several progressive reforms. In 1910, President William Howard Taft appointed Hughes as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. During his tenure on the Supreme Court, Hughes often joined Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. In voting to uphold state and federal regulations. Hughes served as an Associate Justice until 1916, when he resigned from the bench to accept the Republican presidential nomination. Though Hughes was widely viewed as the favorite in the race against incumbent Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, Wilson won a narrow victory. Harding won the 1920 presidential election, Hughes accepted Harding’s invitation to serve as Secretary of State. Serving under Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he negotiated the Washington Naval Treaty, which was designed to prevent a naval arms race among the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. In 1930, President Herbert Hoover appointed him to succeed Chief Justice Taft. Along with Associate Justice Owen Roberts, Hughes emerged as a key swing vote on the bench, positioned between the liberal Three Musketeers and the conservative Four Horsemen. The Hughes Court struck down several New Deal programs in the early and the mid-1930s, but 1937 marked a turning point for the Supreme Court and the New Deal as Hughes and Roberts joined with the Three Musketeers to uphold the Wagner Act and a state minimum wage law. That same year saw the defeat of the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, which would have expanded the size of the Supreme Court. Hughes served until 1941, when he retired and was succeeded by Associate Justice Harlan F. Early life and family. Legal and academic career. Governor of New York. Return to private practice. Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. Hughes at the age of 16. Hughes’s father, David Charles Hughes, immigrated to the United States from Wales in 1855 after he was inspired by The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. David became a Baptist preacher in Glens Falls, New York, and married Mary Catherine Connelly, whose family had been in the United States for several generations. [2] Charles Evans Hughes, the only child of David and Mary, was born in Glens Falls on April 11, 1862. [3][4] The Hughes family moved to Oswego, New York, in 1866, but relocated soon after to Newark, New Jersey, and then to Brooklyn. With the exception of a brief period of attendance at Newark High School, Hughes received no formal education until 1874, instead being educated by his parents. In September 1874, he enrolled in New York City’s prestigious Public School 35, graduating the following year. At the age of 14, Hughes attended Madison University (now Colgate University) for two years before transferring to Brown University. He graduated from Brown third in his class at the age of 19, having been elected to Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year. He was also a member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity, where he would serve as the first international President later on. [6] During his time at Brown, Hughes volunteered for the successful presidential campaign of Republican nominee James A. Garfield, a brother of his in Delta Upsilon where Garfield was an undergraduate at Williams College, and served as the editor of the college newspaper. After graduating from Brown, Hughes spent a year working as a teacher in Delhi, New York. [7] He next enrolled in Columbia Law School, where he graduated first in his class in 1884. [6] That same year, he passed the New York bar exam with the highest score ever awarded by the state. In 1888, Hughes married Antoinette Carter, the daughter of the senior partner of the law firm where he worked. Their first child, Charles Evans Hughes Jr. [9] Hughes and his wife would have one son and three daughters. [10] Their youngest child, Elizabeth Hughes, was one of the first humans injected with insulin, and later served as president of the Supreme Court Historical Society. Hughes with his wife and children, c. ? Hughes took a position with the Wall Street law firm of Chamberlain, Carter & Hornblower in 1883, focusing primarily on matters related to contracts and bankruptcies. He was made a partner in the firm in 1888, and the firm changed its name to Carter, Hughes & Cravath (it later became known as Hughes Hubbard & Reed). Hughes left the firm and became a professor at Cornell Law School from 1891 to 1893. [12] He also joined the board of Brown University and served on a special committee that recommended revisions to New York’s Code of Civil Procedure. Responding to newspaper stories run by the New York World, Governor Frank W. Higgins appointed a legislative committee to investigate the state’s public utilities in 1905. On the recommendation of a former state judge who had been impressed by Hughes’s performance in court, the legislative committee appointed Hughes to lead the investigation. Hughes was reluctant to take on the powerful utility companies, but Senator Frederick C. Stevens, the leader of the committee, convinced Hughes to accept the position. Hughes decided to center his investigation on Consolidated Gas, which controlled the production and sale of gas in New York City. To eliminate or mitigate those abuses, Hughes drafted and convinced the state legislature to pass bills that established a commission to regulate public utilities and lowered gas prices. Seeking to remove Hughes from the investigation, Republican leaders nominated him as the party’s candidate for Mayor of New York City, but Hughes refused the nomination. Gubernatorial portrait of Charles Evans Hughes. Seeking a strong candidate to defeat newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst in the 1906 New York gubernatorial election, President Theodore Roosevelt convinced New York Republican leaders to nominate Hughes for governor. Roosevelt described Hughes as a sane and sincere reformer, who really has fought against the very evils which Hearst denounces… [but is] free from any taint of demagogy. [18] In his campaign for governor, Hughes attacked the corruption of specific companies but defended corporations as a necessary part of the economy. He also called for an eight-hour workday on public works projects and favored prohibitions on child labor. [19] Hughes was not a charismatic speaker, but he campaigned vigorously throughout the state and won the endorsements of most newspapers. [20] Ultimately, Hughes defeated Hearst in a close election, taking 52 percent of the vote. Hughes’s governorship focused largely on reforming the government and addressing political corruption. He expanded the number of civil service positions, increased the power of the public utility regulatory commissions, and won passage of laws that placed limits on political donations by corporations and required political candidates to track campaign receipts and expenditures. [21] He also signed laws that barred younger workers from several dangerous occupations and established a maximum 48-hour workweek for manufacturing workers under the age of 16. To enforce those laws, Hughes reorganized the New York State Department of Labor. Hughes’s labor policies were influenced by economist Richard T. Ely, who sought to improve working conditions for laborers, but rejected the more far-reaching reforms favored by union leaders like Samuel Gompers. Despite his busyness as New York governor, Hughes found time to get involved in religious matters. A lifelong Baptist, he participated in the creation of the Northern Baptist Convention in May 1907. Hughes served the convention as its first president, beginning the task of unifying the thousands of independent Baptist churches across the North into one denomination. Previously, northern Baptists had only connected between local churches through missions societies and benevolent causes. The Northern Baptist Convention would go on to become the historical important American Baptist Churches USA, which made this aspect of Hughes’ life during his governorship a key part of his historical influence. However, Hughes’ political role was changing. He had previously been close with Roosevelt, but relations between Hughes and the president cooled after a dispute over a minor federal appointment. [25] Roosevelt chose not to seek re-election in 1908, instead endorsing Secretary of War William Howard Taft as his preferred successor. Taft won the Republican presidential nomination and asked Hughes to serve as his running mate, but Hughes declined the offer. Hughes also considered retiring from the governorship, but Taft and Roosevelt convinced him to seek a second term. Despite having little support among some of the more conservative leaders of the state party, Hughes won re-election in the 1908 election. Hughes’s second term proved to be less successful than his first, but he increased regulation over telephone and telegraph companies and won passage of the first workers’ compensation bill in U. See also: White Court (judges). Hughes struck up a close friendship with Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. By early 1910, Hughes was anxious to retire from his position as governor. [27] A vacancy on the Supreme Court arose following the death of Associate Justice David J. Brewer, and Taft offered the position to Hughes. Hughes quickly accepted the offer, and he was unanimously confirmed by the Senate on May 2, 1910. [27] Two months after Hughes’ confirmation, but prior to his taking the judicial oath, Chief Justice Melville Fuller died. Taft elevated Associate Justice Edward Douglass White to the position of Chief Justice despite having previously indicated to Hughes that he might select Hughes as Chief Justice. White’s candidacy for the position was bolstered by his long experience on the bench and popularity among his fellow justices, as well as Theodore Roosevelt’s coolness towards Hughes. Taft nominated Willis Van Devanter to succeed White as associate justice. Hughes, who was sworn into office on October 10, 1910, [1] quickly struck up friendships with other members of the Supreme Court, including Chief Justice White, Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, and Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. [29] In the disposition of cases, however, Hughes tended to align with Holmes. He voted to uphold state laws providing for minimum wages, workmen’s compensation, and maximum work hours for women and children. [30] He also wrote several opinions upholding the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause. His majority opinion in Baltimore & Ohio Railroad vs. Interstate Commerce Commission upheld the right of the federal government to regulate the hours of railroad workers. [31] His majority opinion in the 1914 Shreveport Rate Case upheld the Interstate Commerce Commission’s decision to void discriminatory railroad rates imposed by the Railroad Commission of Texas. The decision established that the federal government could regulate intrastate commerce when it affected interstate commerce, though Hughes avoided directly overruling the 1895 case of United States v. He also wrote a series of opinions that upheld civil liberties; in one such case, McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co. Hughes’s majority opinion required railroad carriers to give African-Americans equal treatment. [33] Hughes’s majority opinion in Bailey v. Alabama invalidated a state law that had made it a crime for a laborer to fail to complete obligations agreed to in a labor contract. Hughes held that this law violated the Thirteenth Amendment and discriminated against African-American workers. [31] He also joined the majority decision in the 1915 case of Guinn v. United States, which outlawed the use of grandfather clauses to determine voter enfranchisement. [34] Hughes and Holmes were the only dissenters from the court’s ruling that affirmed a lower court’s decision to withhold a writ of habeas corpus from Leo Frank, a Jewish factory manager convicted of murder in the state of Georgia. Further information: 1916 United States presidential election. Hughes in Winona, Minnesota, during the 1916 presidential campaign campaigning on the Olympian. Taft and Roosevelt endured a bitter split during Taft’s presidency, and Roosevelt challenged Taft for the 1912 Republican presidential nomination. Taft won re-nomination, but Roosevelt ran on the ticket of a third party, the Progressive Party. [36] With the split in the Republican Party, Democratic Governor Woodrow Wilson defeated Taft and Roosevelt in the 1912 presidential election and enacted his progressive New Freedom agenda. [37] Seeking to bridge the divide in the Republican Party and limit Wilson to a single term, several Republican leaders asked Hughes to consider running in the 1916 presidential election. Hughes at first rebuffed those entreaties, but his potential candidacy became the subject of widespread speculation and polls showed that he was the preferred candidate of many Republican voters. By the time of the June 1916 Republican National Convention, Hughes had won two presidential primaries, and his backers had lined up the support of numerous delegates. Hughes led on the first presidential ballot of the convention and clinched the nomination on the third ballot. Hughes accepted the nomination, becoming the first and only sitting Supreme Court Justice to serve as a major party’s presidential nominee, and submitted his resignation to President Wilson. Roosevelt, meanwhile, declined to run again on a third party ticket, leaving Hughes and Wilson as the only major candidates in the race. 1916 electoral vote results. Because of the Republican Party’s dominance in presidential elections held since the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Hughes was widely regarded as the favorite even though Wilson was the incumbent. His candidacy was further boosted by his own reputation for intelligence, personal integrity, and moderation. Hughes also won the public support of both Taft and Roosevelt, though Roosevelt remained uneasy with Hughes, whom he feared would be a Wilson with whiskers. However, the split in Republican ranks remained a lingering issue, and Hughes damaged his campaign by inadvertently snubbing Hiram Johnson, the Governor of California who had been Roosevelt’s running mate in the 1912 election. [39] Because of Hughes’s opposition to the Adamson Act and the Sixteenth Amendment, most former Progressive Party leaders endorsed Wilson. [40] By election day, Hughes was still generally considered to be the favorite. However, Wilson swept the Solid South and won several victories in the Midwest, where his candidacy was boosted by a strong pacifist sentiment. Wilson ultimately prevailed after winning the state of California by fewer than 4,000 votes. The next month, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war, and the United States entered World War I. [43] Hughes supported Wilson’s military policies, including the imposition of the draft, and he served as chairman of New York City’s draft appeals board. He also investigated the aircraft industry on behalf of the Wilson administration, exposing numerous inefficiencies. [45] He sought to broker a compromise between President Wilson and Senate Republicans regarding US entrance into Wilson’s proposed League of Nations, but the Senate rejected the League and the Treaty of Versailles. With Wilson’s popularity declining, many Republican leaders believed that their party would win the 1920 presidential election. Hughes remained popular in the party, and many influential Republicans favored him as the party’s candidate in 1920. Hughes was struck by personal disaster when his daughter, Helen, died in 1920 of tuberculosis, and he refused to allow his name to be considered for the presidential nomination at the 1920 Republican National Convention. The party instead nominated a ticket consisting of Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio and Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts. [47] The Republican ticket won in a landslide, taking 61 percent of the popular vote. Further information: Presidency of Warren G. Harding and Presidency of Calvin Coolidge. Hughes’s residence in 1921. Shortly after Harding’s victory in the 1920 election, Hughes accepted the position of Secretary of State. [48] After the death of Chief Justice White in May 1921, Hughes was mentioned as a potential successor. Hughes told Harding he was uninterested in leaving the State Department, and Harding instead appointed former President Taft as the Chief Justice. Harding granted Hughes a great deal of discretion in his leadership of the State Department and US foreign policy. [50] Harding and Hughes frequently communicated, Hughes worked within some broad outlines, and the president remained well-informed. But the president rarely overrode any of Hughes’s decisions, with the big and obvious exception of the League of Nations. After taking office, Pres. Harding hardened his stance on the League of Nations, deciding the US would not join even a scaled-down version. [52] Or, another view is that Harding favored joining with reservations when he assumed office on March 4, 1921, but that Senators staunchly opposed (the “Irreconcilables”), per Ron Powaski’s 1991 book, threatened to wreck the new administration. Hughes favored membership in the League. Early in his tenure as Secretary of State, he asked the Senate to vote on the Treaty of Versailles, [54] but he yielded to either Harding’s changing views and/or political reality within the Senate. Instead, he convinced Harding of the necessity of a separate treaty with Germany, resulting in the signing and eventual ratification of the U. [55] Hughes also favored US entrance into the Permanent Court of International Justice, but was unable to convince the Senate to provide support. Hughes’s major initiative in office was naval disarmament, as he sought to prevent a naval arms race among the three great naval powers of Britain, Japan, and the United States. After Senator William Borah led passage of a resolution calling on the Harding administration to negotiate an arms reduction treaty with Japan and Britain, Hughes convinced those countries as well as Italy and France to attend a naval conference in Washington. Hughes selected an American delegation consisting of himself, former Secretary of State Elihu Root, Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and Democratic Senator Oscar Underwood. Hughes hoped that the selection of Underwood would ensure bipartisan support for any treaty arising from the conference. Prior to the conference, Hughes had carefully considered possible treaty terms since each side would seek terms that would provide their respective navy with subtle advantages. Knowing that US and foreign naval leaders would resist his proposal, he anxiously guarded it from the press, but he won the support of Root, Lodge, and Underwood. The Washington Naval Conference opened in November 1921, attended by five national delegations, and, in the gallery, hundreds of reporters and dignitaries such as Chief Justice Taft and William Jennings Bryan. On the first day of the conference, Hughes unveiled his proposal to limit naval armaments. [58] The British delegation, led by Arthur Balfour, supported the proposal, but the Japanese delegation, under the leadership of Kato Tomosaburo, asked for several modifications. Kato asked that the ratio be adjusted to 10:10:7 and refused to destroy the Mutsu, a dreadnought that many Japanese saw as a symbol of national pride. Kato eventually relented on the naval ratios, but Hughes acquiesced to the retention of the Mutsu, leading to protests from British leaders. Hughes clinched an agreement after convincing Balfour to agree to limit the size of the Admiral-class battlecruisers despite objections from the British navy. Hughes also won agreement on the Four-Power Treaty, which called for a peaceful resolution of territorial claims in the Pacific Ocean, as well as the Nine-Power Treaty, which guaranteed the territorial integrity of China. News of the success of the conference was warmly received around the world. Roosevelt would later write that the conference brought to the world the first important voluntary agreement for limitation and reduction of armament. See also: Banana Wars. Hughes (fourth from right) leads a delegation to Brazil with Carl Theodore Vogelgesang in 1922. In the aftermath of World War I, the German economy struggled from the strain of postwar rebuilding and war reparations owed to the Entente, while the Entente powers in turn owed large war debts to the United States. Though many economists favored cancellation of all European war debts, French leaders were unwilling to cancel the reparations, and Congress refused to consider forgiving the war debts. Hughes helped organize the creation of an international committee of economists to study the possibility of lowering Germany’s reparations, and Hughes selected Charles G. Dawes to lead that committee. The resulting Dawes Plan, which provided for annual payments by Germany, was accepted at a 1924 conference held in London. Hughes sought better relations with the countries of Latin America, and he favored removing US troops when he believed that doing so was practicable. He formulated plans for the withdrawal of US soldiers from the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua but decided that instability in Haiti required the continued presence of U. He also settled a border dispute between Panama and Costa Rica by threatening to send soldiers into Panama. Hughes was the keynote speaker at the 1919 National Conference on Lynching. Time cover, December 29, 1924. Hughes stayed on as Secretary of State in the Coolidge administration after the death of Harding in 1923, but he left office in early 1925. He also served as a special master in a case concerning Chicago’s sewage system, was elected president of the American Bar Association, and co-founded the National Conference on Christians and Jews. State party leaders asked him to run against Al Smith in New York’s 1926 gubernatorial election, and some national party leaders suggested that he run for president in 1928, but Hughes declined to seek public office. After the 1928 Republican National Convention nominated Herbert Hoover, Hughes gave Hoover his full support and campaigned for him across the United States. Hoover won the election in a landslide and asked Hughes to serve as his Secretary of State, but Hughes declined the offer to keep his commitment to serve as a judge on the Permanent Court of International Justice. See also: Hughes Court, List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Hughes Court, and Herbert Hoover Supreme Court candidates. Portrait of Hughes as Chief Justice. On February 3, 1930, President Hoover nominated Hughes to succeed Chief Justice Taft, who was gravely ill. Though many had expected Hoover to elevate his close friend, Associate Justice Harlan Stone, Hughes was the top choice of Taft and Attorney General William D. [64][65] Though Hughes had compiled a progressive record during his tenure as an Associate Justice, by 1930 Taft believed that Hughes would be a consistent conservative on the court. [66] The nomination faced resistance from progressive Republicans such as senators George W. Norris and William E. Borah, who were concerned that Hughes would be overly friendly to big business after working as a corporate lawyer. [67][68] Many of those progressives, as well some Southern states’ rights advocates, were outraged by the Taft Court’s tendency to strike down state and federal legislation on the basis of the doctrine of substantive due process and feared that a Hughes Court would emulate the Taft Court. [69] Adherents of the substantive due process doctrine held that economic regulations such as restrictions on child labor and minimum wages violated freedom of contract, which, they argued, could not be abridged by federal and state laws because of the Fifth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment. After a brief but bitter confirmation battle, Hughes was confirmed by the Senate in a 52-26 vote, [71] and took his judicial oath of office on February 24, 1930. [1] Hughes’s son, Charles Jr. Was subsequently forced to resign as Solicitor General after his father took office as Chief Justice. [72] Hughes quickly emerged as a leader of the Court, earning the admiration of his fellow justices for his intelligence, energy, and strong understanding of the law. [73] Shortly after Hughes was confirmed, Hoover nominated federal judge John J. Parker to succeed deceased Associate Justice Edward Terry Sanford. The Senate rejected Parker, whose earlier rulings had alienated labor unions and the NAACP, but confirmed Hoover’s second nominee, Owen Roberts. [74] In early 1932, the other justices asked Hughes to request the resignation of Oliver Wendell Holmes, whose health had declined as he entered his nineties. Hughes privately asked his old friend to retire, and Holmes immediately sent a letter of resignation to President Hoover. To replace Holmes, Hoover nominated Benjamin N. Cardozo, who quickly won confirmation. The early Hughes Court was divided between the conservative “Four Horsemen” and the liberal “Three Musketeers”. [a][77] The primary difference between these two blocs was that the Four Horsemen embraced the substantive due process doctrine, but the liberals, including Louis Brandeis, advocated for judicial restraint, or deference to legislative bodies. [78] Hughes and Roberts would be the swing justices between the two blocs for much of the 1930s. In one of the first major cases of his tenure, Hughes joined with Roberts and the Three Musketeers to strike down a piece of state legislation in the 1931 landmark case of Near v. In his majority opinion, Hughes held that the First Amendment barred states from violating freedom of the press. Hughes also wrote the majority opinion in Stromberg v. California, which represented the first time the Supreme Court struck down a state law on the basis of the incorporation of the Bill of Rights. [b][77] In another early case, O’Gorman & Young, Inc. During Hoover’s presidency, the country plunged into the Great Depression. [81] As the country faced an ongoing economic calamity, Franklin D. Roosevelt decisively defeated Hoover in the 1932 presidential election. [82] Responding to the Great Depression, Roosevelt passed a bevy of domestic legislation as part of his New Deal domestic program, and the response to the New Deal became one of the key issues facing the Hughes Court. In the Gold Clause Cases, a series of cases that presented some of the first major tests of New Deal laws, the Hughes Court upheld restrictions on the ownership of gold that were favored by the Roosevelt administration. [83] Roosevelt, who had expected the Supreme Court to rule adversely to his administration’s position, was elated by the outcome, writing that as a lawyer it seems to me that the Supreme Court has at last definitely put human values ahead of the’pound of flesh’ called for by a contract. [84] The Hughes Court also continued to adjudicate major cases concerning the states. In the 1934 case of Home Building & Loan Ass’n v. Blaisdell, Hughes and Roberts joined the Three Musketeers in upholding a Minnesota law that established a moratorium on mortgage payments. [83] Hughes’s majority opinion in that case stated that while an emergency does not create power, an emergency may furnish the occasion for the exercise of power. Beginning with the 1935 case of Railroad Retirement Board v. Roberts started siding with the Four Horsemen, creating a majority bloc that struck down New Deal laws. [86] The court held that Congress had, in passing an act that provided a mandatory retirement and pension system for railroad industry workers, violated due process and exceeded the regulatory powers granted to it by the Commerce Clause. [87] Hughes strongly criticized Roberts’s majority opinion in his dissent, writing that the power committed to Congress to govern interstate commerce does not require that its government should be wise, much less that it be perfect. The power implies a broad discretion. [86] Nonetheless, in May 1935, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down three New Deal laws. Writing the majority opinion in A. United States, Hughes held that Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 was doubly unconstitutional, falling afoul of both the Commerce Clause and the nondelegation doctrine. In the 1936 case of United States v. Butler, Hughes surprised many observers by joining with Roberts and the Four Horsemen in striking down the Agricultural Adjustment Act. [88] In doing so, the court dismantled the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the major New Deal agricultural program. [89] In another 1936 case, Carter v. The Supreme Court struck down the Guffey Coal Act, which regulated the bituminous coal industry. Hughes wrote a concurring opinion in Carter in which he agreed with the majority’s holding that Congress could not use its Commerce Clause powers to regulate activities and relations within the states which affect interstate commerce only indirectly. In the final case of the 1936 term, Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo, Roberts joined with the Four Horsemen in striking down New York’s minimum wage law. [90] President Roosevelt had held up the New York minimum wage law as a model for other states to follow, and many Republicans as well as Democrats attacked the decision for interfering with the states. [91] In December 1936, the court handed down its near-unanimous opinion in United States v. Upholding a law that granted the president the power to place an arms embargo on Bolivia and Paraguay. Justice Sutherland’s majority opinion, which Hughes joined, explained that the Constitution had granted the president broad powers to conduct foreign policy. The Hughes Court in 1937, photographed by Erich Salomon. Roosevelt won re-election in a landslide in the 1936 presidential election, and congressional Democrats grew their majorities in both houses of Congress. [93] As the Supreme Court had already struck down both the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the president feared that the court would next strike down other key New Deal laws, including the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (also known as the Wagner Act) and the Social Security Act. [94] In early 1937, Roosevelt proposed to increase the number of Supreme Court seats through the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 (also known as the “court-packing plan”). Roosevelt argued that the bill was necessary because Supreme Court justices were unable to meet their case load. With large Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, Roosevelt’s bill had a strong chance of passage in early 1937. [95] However, the bill was poorly received by the public, as many saw the bill as power grab or as an attack on a sacrosanct institution. [96] Hughes worked behind the scenes to defeat the effort, rushing important New Deal legislation through the Supreme Court in an effort to quickly uphold the constitutionality of the laws. [97] He also sent a letter to Senator Burton K. Hughes’s letter had a powerful impact in discrediting Roosevelt’s argument about the practical need for more Supreme Court justices. While the debate over the court-packing plan continued, the Supreme Court upheld, in a 5-4 vote, the state of Washington’s minimum wage law in the case of West Coast Hotel Co. Joined by the Three Musketeers and Roberts, Hughes wrote the majority opinion, [99] which overturned the 1923 case of Adkins v. [100] In his majority opinion, Hughes wrote that the “Constitution does not speak of freedom of contract”, and further held that the Washington legislature was entitled to adopt measures to reduce the evils of the’sweating system,’ the exploiting of workers at wages so low as to be insufficient to meet the bare cost of living. “[101] Because Roberts had previously sided with the four conservative justices in Tipaldo, a similar case, it was widely perceived that Roberts agreed to uphold the constitutionality of minimum wage as a result of the pressure that was put on the Supreme Court by the court-packing plan (a theory referred to as “the switch in time that saved nine). [102] However, Hughes and Roberts would both later indicate that Roberts had committed to changing his judicial stance on state minimum wage law months before Roosevelt announced his court-packing plan. [103] Roberts had voted to grant certiorari to hear the Parrish case even before the 1936 presidential election, and oral arguments for the case had taken place in late 1936. [104] In an initial conference vote held on December 19, 1936, Roberts had voted to uphold the law. [105] Scholars continue to debate why Roberts essentially switched his vote with regards to state minimum wage laws, but Hughes may have played an important role in influencing Roberts to uphold the law. Weeks after the court handed down its decision in Parrish, Hughes wrote for the majority again in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp.. Joined by Roberts and the Three Musketeers, Hughes upheld the constitutionality of the Wagner Act. The Wagner Act case marked a turning point for the Supreme Court, as the court began a pattern of upholding New Deal laws. [107] Later in 1937, the court upheld both the old age benefits and the taxation system established by the Social Security Act. Meanwhile, conservative Associate Justice Willis Van Devanter announced his retirement, undercutting Roosevelt’s arguments for the necessity of the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. [108] By the end of the year, the court-packing plan had died in the Senate, and Roosevelt had been dealt a serious political wound that emboldened the conservative coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans. [109] However, throughout 1937, Hughes had presided over a massive shift in jurisprudence that marked the end of the Lochner era, a period during which the Supreme Court had frequently struck down state and federal economic regulations. [100] Hugo Black, Roosevelt’s nominee to succeed Van Devanter, was confirmed by the Senate in August 1937. [110] He was joined by Stanley Forman Reed, who succeeded Sutherland, the following year, leaving pro-New Deal liberals with a majority on the Supreme Court. Associate Justice William O. Douglas served alongside Hughes on the Supreme Court. After 1937, the Hughes Court continued to uphold economic regulations, with McReynolds and Butler often being the lone dissenters. [113] The liberal bloc was strengthened even further in 1940, when Butler was succeeded by another Roosevelt appointee, Frank Murphy. [114] In the case of United States v. Justice Stone’s majority opinion articulated a broad theory of deference to economic regulations. Carolene Products established that the Supreme Court would conduct a “rational basis review” of economic regulations, meaning that the Court would only strike down a regulation if legislators lacked a “rational basis” for passing the regulation. The Supreme Court showed that it would defer to state legislators in the cases of Madden V. Kentucky and Olsen v. [115] Hughes joined the majority in another case, United States v. Which upheld the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The Hughes Court also faced several civil rights cases. Hughes wrote the majority opinion in Missouri ex rel. Canada, which required the state of Missouri to either integrate its law school or establish a separate law school for African-Americans. [117] He joined and helped arrange unanimous support for Black’s majority opinion in Chambers v. Florida, which overturned the conviction of a defendant who had been coerced into confessing a crime. [118] In the 1940 case of Minersville School District v. Gobitis, Hughes joined the majority decision, which held that public schools could require students to salute the American flag despite the students’ religious objections to these practices. Hughes began to consider retiring in 1940, partly due to the declining health of his wife. In June 1941, he informed Roosevelt of his impending retirement. [120] Hughes suggested that Roosevelt elevate Stone to the position of Chief Justice, a suggestion that Roosevelt accepted. [121] Hughes retired in 1941, and Stone was confirmed as the new Chief Justice, beginning the Stone Court. During his retirement, Hughes generally refrained from re-entering public life or giving advice on public policy, but he agreed to review the United Nations Charter for Secretary of State Cordell Hull, [122]and recommending that President Harry S. Truman appoint Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice after the death of Stone. He lived in New York City with his wife, Antoinette, until she died in December 1945. [123] On August 27, 1948, at the age of 86, Hughes died in what is now the Tiffany Cottage of the Wianno Club in Osterville, Massachusetts. When he died, Hughes was the last living Justice to have served on the White Court. He is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City. In the evaluation of historian Dexter Perkins, in domestic politics. Hughes was a happy mixture of the liberal and the conservative. He was wise enough to know that you cannot preserve a social order unless you eradicate its abuses, and so he was never a stand-patter. On the other side he could see that change carried perils as well as promises. Sometimes he stood out against these perils. He was not always wise, it is true. We do not have to agree with him in everything. But he stands a noble and constructive figure in American life. In the consensus view of scholars, Hughes as a diplomat was. An outstanding Secretary of State. He possessed a clear vision of America’s position in the new international system. The United States would be a world leader, not only in terms of its ability to provide material progress, but also by its advocacy of diplomacy and arbitration over military force. Hughes was fully committed to the supremacy of negotiation and the maintenance of American foreign policy. This quality was combined with an ability to maintain a clear sense of the larger goals of American diplomacy…. He was able to maintain control over US foreign policy and take the country into a new role as a world power. Hughes has been honored in a variety of ways, including in the names of several schools, rooms, and events. Other things named for Hughes include the Hughes Range in Antarctica. On April 11, 1962, the 100th anniversary of Hughes’s birth, the U. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. [127] The Charles Evans Hughes House, now the Burmese ambassador’s residence, in Washington, D. Was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1972. Judge Learned Hand once observed that Hughes was the greatest lawyer he had ever known, except that his son Charles Evans Hughes Jr. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Autographs\Historical”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.

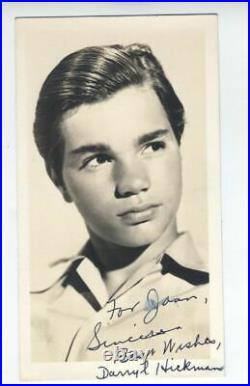

Darryl Hickman Child Actor Signed Photo Dobie Gillis Grapes Of Wrath Autograph